He composed a melancholy pigeon

mainFrom the Lebrecht Album of the Week:

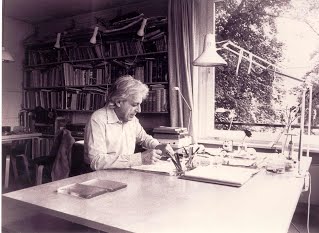

Among composers of the post-War avant-garde, Ligeti is now the most performed. You can go from one end of the year to the other without hearing a note of Boulez or Stockhausen, but Ligeti – who died sooner than the other two, in 2006 – is somehow freshest in mind. His opera Le grand macabre is practically made-for-TV with its post-modern anarchic comedy and his violin concerto is a back-to Bartok contemporary classic.

These piano studies, written in the 1980s and 1990s when Ligeti had fallen out with the didactic avant-gardists, are fiendishly difficult to play and irresistibly easy on the ear…

Read on here.

And here.

En francais ici.

In Czech here.

Comments