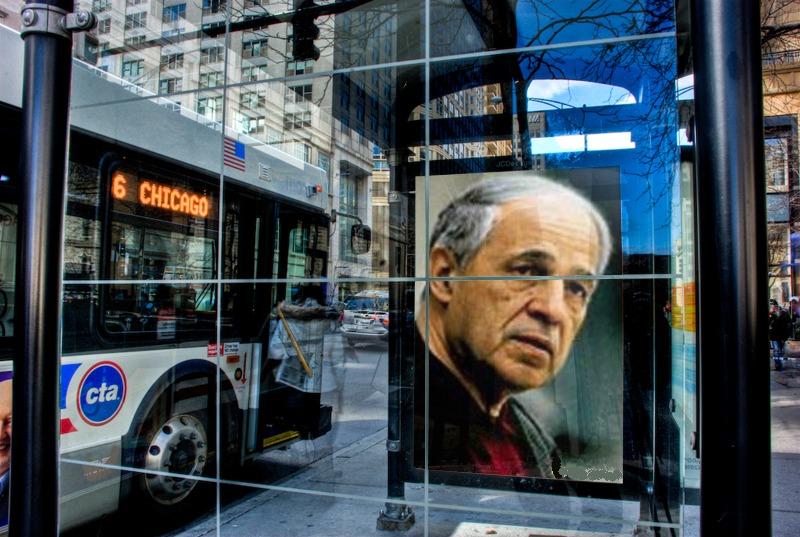

Boulez cannot hear beyond his knee-jerk aversion to tonality

mainFrom composer Matthew Aucoin’s demolition job in the New York Review of Books of a new collection of Boulez pensées:

Boulez cannot hear past his knee-jerk aversion to anything resembling functional tonality in the work of a twentieth-century composer. In the spirit of experimentation, Stravinsky was willing to run the risk of sounding innocent or even sentimental—a risk Boulez would never have admitted to his oeuvre’s steel fortress. This reductive attitude, this refusal to listen past Stravinsky’s surfaces and meet the music on its own terms, is a harbinger of the bullying narrow-mindedness that Boulez brings to his analyses of more recent music.

Over the course of Music Lessons, Boulez trains the automatic weapon of his disdain on practically every school of twentieth-century musical thought. He does not reserve his ire, as I expected he might, for composers whom he considers backward-looking; he is equally intolerant of artists who dare to make music using new sound sources (often electronic ones), who experiment with improvisatory practices, or who use unconventional notation. Given the ferocity of these broadsides, it is perhaps merciful that Boulez almost never specifies who or what he’s attacking, but this also makes it impossible to take his criticisms seriously. There is nothing more boring than the spittle-spewing invective of a demagogue railing against ill-defined, possibly illusory enemies, and unfortunately this book seethes with such denunciations….

And more here.

Comments