Beethoven: is this the end?

mainWelcome to the 124th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

String Quartet No. 16 op. 135

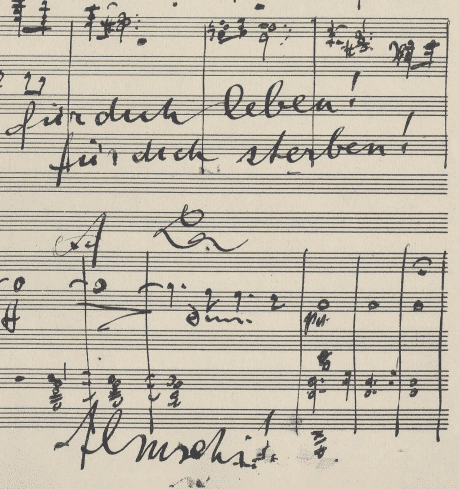

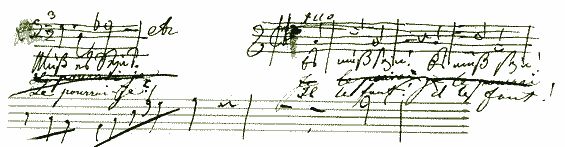

Is this his last word? The finale of opus 135 is titled ‘Der schwer gefaßte Entschluss’ – the very difficult decision. Under the opening chords, which are marked slow, Beethoven inserted the words ‘Muss es sein?’ (must it be?) and as the quicker main theme arrives, ‘Es muss sein!’ (It must be!). Interpreters down the ages have assumed that he was anticipating his own death.

But was he? The ‘Muss es sein?’ is played gravely by viola and cello before giving way to an irresistible response by the two violins ‘Es muss sein!’ No sign of resignation by the composer.

Thirty years later the original publisher, Moritz Schlesinger, recalled: Regarding the enigmatic phrase Muss es sein? that arises in the last quartet, I think I can explain its significance better than most people, as I possess the original manuscript with the words written in his own hand, and when he sent them he wrote as follows; ‘You can translate the Muss es sein as showing that I have been unlucky, not only because it has been extremely difficult to write this when I had something much bigger in my mind, and because I have only written this in accordance with my promise to you, and because I am in dire need of money, which is hard to come by; it has also happened that I was anxious to send the work to you in parts, to facilitate engraving, and in all Mödlingen (he was living there then) I could not find a single copyist, and so have had to copy it out myself, and you can imagine what a business it has been!’

In other words, the painstricken composer was getting on with life as usual. His nephew Karl had attempted to commit suicide in an attention-seeking gesture, which could be the ‘bigger things’ he had in mind in the letter, and there was never enough money to pay the bills. One contemporary anecdote has it that an amateur musician, Ignaz Dembscher, had called round to borrow parts for the opus 130 quartet that he wanted to play with his pals. Beethoven demanded a loan fee of fifty florins. ‘Must that be?’ said the wealthy fellow. ‘It must be,’ snapped Beethoven, ‘out with your wallet.’

Take this with as much salt as you need. The facts of the inscription override further speculation. Beethoven, aware of his mortality, found it necessary to share his agony with the manuscript he was composing, just as Gustav Mahler would do 90 years later in a series of heart-rending outcries around the closing pages of his ninth and tenth symphonies. While composing, Mahler cried out in desperation to his errant wife and his distant God. He would have known that Beethoven, while composing his final work, had done much the same.

We have no idea what Beethoven might have written next had he survived the final illness of February and March 1827. There are hints that he saw this 16th quartet not as a continuation of its predecessors but as the first of a brand-new triptych. Certainly the opus 135 has less in common with opp 130, 131 and 135 than these three works do with each other. One might also argue that the level of invention has dropped here appreciably from those heights. The 16th is an important string quartet, albeit less of a masterpiece than its forbears.

Beethoven’s final weeks were shadowed as ever by financial worries. Early in February he wrote to the Philharmonic Society in London, asking if they might perform a benefit concert on his behalf. George Smart and Ignaz Moscheles, sensing his need, called a board meeting and resolved to send him a hundred pounds. Beethoven, overwhelmed by the gift, called a lawyer and remade his will, leaving everything to his errant nephew Karl who, after the composer’s death, turned into a model civil servant, dutiful husband and loving father of four daughters and a son. He died in 1858 at the age of 52.

On March 20, Beethoven told his young composer friend Johann Nepomuk Hummel, ‘I shall soon, no doubt, be going above’. He thanked Hummel’s wife Elisabeth, a well-known oper singer, for freshening his face with her handkerchief. He continued to receive visitors until he lost consciousness on March 24. Two days later, in the thick of a terrifying thunderstorm, he died at three o’clock in the afternoon. Buried at Währing, his remains were transferred in 1888 to a grove of honour in Vienna’s central cemetery.

The 16th string quartet, last word or not, is as widely recorded as the rest. The ‘mus es sein’ conversation in the 1933 Busch Quartet account is irresistibly convincing, like four philosophers contemplating eternity over a few jars of beer. The Alban Berg Quartet (1989) turn the phrase into something more momentous and ominous. If Beethoven really meant Muss es sein? as a joke, they miss the punchline. Much more convincing are the Cuarteto Casals (2017) with a tentative framing of the question and a vigorous rebuttal by way of response. This deeply felt, well thought out reading leaves the listener to decide for him or herself what might have been going through Beethoven’s mind as he worked his way through his final contribution to the treasury of western civilisation. I also find much to cherish in the Brodsky Quartet’s 2017 interpretation, especially the whispering caress of the third movement with another phrase of the Kol Nidrei before the crunch question of Muss es sein? comes in to play.

There was never a composer like Beethoven and there will never be another. But each time I come to the end of his works I want to start again from the beginning. There is just so much to learn from this prodigous, attractive, ever-expanding creative mind.

Comments