The Hungarian who kept Beethoven alive

mainWelcome to the 114th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Liszt/Beethoven: The 9 symphonies

In the quarter-century after Beethoven’s death in 1827, only a small section of the public had access to his larger works. Orchestras were scarce and of uneven quality, while many concerts were exclusive, unavailable to the non-invited.

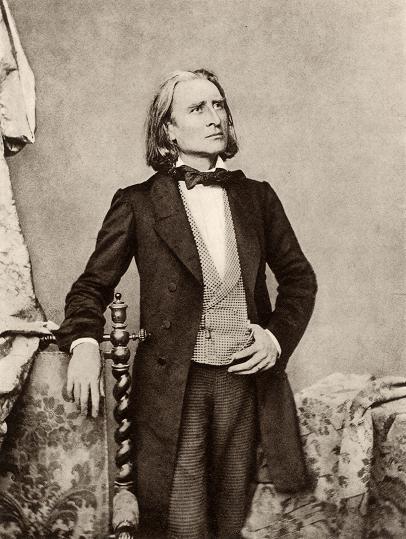

In this gathering oblivion, no-one did more to perpetuate Beethoven’s music and memory than the Hungarian pianist-composer Franz Liszt. Touring the length and breath of Europe from Russia to Ireland, Baltic to Balkans, Liszt performed in addition to his own music the transcriptions he made of works that he felt ought to be more widely known. While his piano ‘reminiscences’ of Italian opera hits were guaranteed crowd-pleasers, Liszt leavened his menu with Beethoven for the purpose of improving public taste.

Starting with truly imaginative and beautiful renditions for solo piano of the song ‘Adelaide’ and the early Septet, Liszt did not transcribe the Beethoven symphonies until he was past 50. He read the proofs before publication while staying in the Vatican, assisting at Mass as a sacristan while trying to sort out his marital problems. Beethoven was as much a refuge as faith to this troubled, trifurcated musician-priest who shuttled away his life between Weimar, Budapest and Rome, with occasional jaunts to Bayreuth.

Liszt’s piano reductions of the Beethoven symphonies are hardly ever given nowadays in a concert hall. His biographer Alan Walker writes: ‘They dispel the popular view of him as a showman, taking other composers’ works and turning them into a fireworks display for his own glorification. The act of self denial,.. suppressing his own creative impulses in the interests of Beethoven’s music, has few parallels.’

All of his symphonic transcriptions have been recorded. You may be surprised to see below which musical minds alighted on them.

1st Symphony

The French-Cypriot pianist Cyprien Katsaris recorded all nine symphonies in the 1980s and had them reissued by Warner in 2006. While the performances are of a high standard, the sound is less than ideal and there are few leaps of imagination in the interpretations. The first two symphonies give a good flavour of a decent series. Idil Biret’s 1985 Brussels performances are also marred by undistinguished sound. The 2020 production for Jean-Louis Haguenauer, a teacher at the University of Indiana, Bloomington, is clearer and brighter by far and his opening adagio is also the most expressive.

2nd symphony

Recorded at St Martin’s Church, East Woodhay, in Hampshire, this Naxos performance by the Russian-Swiss pianist Konstantin Scherbakov is wonderfully contemplative, as if he captured Beethoven in a matchbox and observes him for private delectation. The sound is exactly what you’d expect from an English country church and a professional recording team; these stadards are maintained throughout this cycle.

3rd symphony, Eroica

The veteran French virtuoso Georges Pludermacher enters the hustings with an interpretation that errs on the side of Napoleonic magniloquence, an approach that Beethoven himself reconsidered. Pludermacher’s funeral march is wonderfully sombre, the best part of this performance. For the whole symphony, I prefer the 2019 release by the Italian Gabriele Baldocci, an occasional partner of Martha Argerich. His is another evocative country-church recording, made at Chiese di Sant’Apollinare, Monticello di Lonigo.

4th symphony

The Frenchman Alain Planès, a former soloist with Pierre Boulez’s ensemble, adds a kind of pointillist modernism to Liszt’s scores, as if John Cage had rethought them for a prepared piano. He’s exceptionally listenable in the slow movements. Otherwise, Katsaris and Biret will do.

5th symphony

Hold on to your hat. This is Glenn Gould playing Beethoven’s fifth symphony on a piano whoch, while in tune, had possibly seen better days. You will soon overcome that reservation because this is one of the most gripping readings of the symphony to be found anywhere, whether full orchestra or solo piano. Gould’s recapitulation of the opening theme alone ought to be taught in every conducting course on earth.

And if that’s not surprise enough, here is one of the great musical minds of Vienna, the period-piano expert Paul Badura-Skoda, giving the symphony the benefit of his immense knowledge of Beethovenian timbre. Wonderfully light in the upper register, Badura-Skoda finds colours that no-one else suspects – albeit without creating the rounded interpretation that Gould so monumentally delivers.

6th symphony, Pastoral

Glenn Gould again – the perfect companion in the first movement and an absolute terror in the storm. One of the great Pastorals, by a country mile.

I also love the bucolic atomosphere conjured by Ashley Wass on an original 1820s fortepiano in an English country house; it’s a distinctive sound, just perfect for this piece. You might like to sample the Frenchman Michel Dalberto, a lovely storyteller on a very recent Harmonia Mundi compilation of the complete Liszt/Beethoven transcriptions.

7th symphony

You are about the hear the most phenomenal pair of hands I ever had the good fortune to encounter. Ronald Smith was an Englishman in pebble glasses who played the most difficult pieces of Busoni and was solely responsible for the revival of the near-unplayable Alkan, the only 19th century pianist who put Liszt in the shade. Ronald, whom I got to know through his Alkan endeavours, was going blind and consigned a huge amount of music to memory. What we hear in his account of the Liszt/Beethoven 7th is a pianist as gifted as Liszt making sense of a composer as great as Beethoven. I don’t think I breathed at all during the second movement.

By way of context, listen to Jean-Claude Pennetier and Michel Dalberto play a four-hand version, which appears to contain fewer notes than Ronald Smith manages with two hands.

8th symphony

The Russian Yury Martynov, a teacher at the Tchaikovsky conservatoire in Moscow, recorded the cycle in Setember 2013 at the Doopsgezinde Gemeente Church in Haarlem, in the Netherlands. Using a mid-19th century concert grand, he conjures more of Liszt than he does of Beethoven. The modest eight symphony responds particularly well to this more showy approach.

9th symphony

It’s unrealistic to imagine that the Ninth can be shrunk to living room size and none of the interpretations available is entirely successful. I am drawn to a lyrical 2009 reading by the Italian Maurizio Baglini, at times so leisurely it almost comes to a halt. Katsaris, Biret and Scherbakov are also fine, but I am most convinced in this symphony by the 2008 four-hand version played by Leon McCawley and Ashley Wass, two young men in a hurry.

Just as Liszt was when he wrote these nine transcriptions.

Comments