Recording from the Auditorium Radio El Mundo, Buenos Aires, 1949. She is so much faster than the sluggish orchestra.

Recording from the Auditorium Radio El Mundo, Buenos Aires, 1949. She is so much faster than the sluggish orchestra.

Große Fuge for String Quartet in B flat major op. 133

Beethoven made a rare admission of error when he extracted the 15-minute finale from his 13th string quartet and had it published as a work in its own right. Not only did he recognise that the long fugue would have left the quartet lop-sided but he was able to acknowledge the awkward independence of this single movement, the most important fugue in the history of music after J S Bach’s Art of the Fugue.

Anything that calls itself a fugue is innately ambiguous. In music it is a work of two or more themes that interleave and play against each other, often with more voices entering the conversation. In psychiatry, the term is used to express loss of identity. Both meanings apply to Beethoven’s great fugue. Unable to hear a note that he is writing, he knows that his mission in life is fulfilled. He does not have to explain himself to the world any more. But who is he writing for? He is free to compose as unapproachably as the mood takes him.

He gave the work a French subtitle: ‘tantôt libre, tantôt recherchée’, meaning: a bit free, a bit remote. Which is not much help to grasping what he wants. He told a violinist: ‘You will find a new way of treating it.’ Even less help. He has written an enigma, and he knew it.

Some of the best quartets in history threw up their hands in despair. Adolf Busch, whose quartet covered the late quartets in the 1930, left the Grosse Fuge alone as a quartet and assigned it to a string orchestra. The Budapest String Quartet, also recording in the late 1930s, played the opening – contrary to common practice – as a slow, romantic proposition. Most hear anger in the introduction. Many force it to the point of ugliness. As late as 1947, a US composer Daniel Gregory Mason, called the Fuge ‘Long, complicated and through many hearings repellent if not unintelligible.’ Twenty years later, the Canadian pianist Glenn Gould, never knowingly understated, announced that ‘for me, the Grosse Fuge is not only the greatest work Beethoven ever wrote but just about the most astonishing piece in musical literature.’

So where do we turn for elucidation? The Barylli Quartet, made up of Vienna Philharmonic players and recording in 1952, have a settled point of view. As orchestral musicians, they prioritise togetherness over conflict and their account of the Fuge is both lucid and cohesive, if without the anarchy that Beethoven wrote into the piece. The Hollywood String Quartet, formed by the violinist Fleix Slatkin and his cellist wife Eleanor Aller, gave a marvellously intense 1957 performance in Edinburgh. The sound is recessed but the momentum is irresistible.

The Guarneri Quartet (1968) hedge their bets at first, alternating aggression with conciliation. Twenty years later, in a second recording for Philips, they miraculously resolve their difference and yield one of the landmark recordings, rich in psychological complexity and propulsive attentivess.

Out of Russia, the Borodin Quartet recording in 2000 give an account full of fascination and contradiction. Although only the cellist Valentin Berlinsky survives by the time from the original quartet formation, their shared history of making music under the censorship of Stalin and Sovietism, of perceiving Beethoven through the lens of Berlinsky’s friend Dmitri Shostakovich, rings through in this performance in surprisingly vivid sound. The foreboding sense of ‘this is not going to end well’ is mitigated every few minutes with ‘maybe it might’. The question is left open to the last I discovered this recording quite late in the day and am drawn back often to its indeterminacy.

The Alban Berg Quartet‘s later interpretation is too prescriptive, too self-confident for my liking, though its decisiveness set the tone for many younger ensembles. Faced with their own mortality, the Amadeus are hesitant and a little afraid, as we all must be. The Quartetto Italiano, in one of their late releases, are the most human of all, unfailingly moving in their depiction of Beethoven’s rage against, what the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas called ‘the dying of the light’. I doubt there is a more absorbing recording. After hearing this again, for the present survey, I stopped looking any further. It gives the impression of being the last word on the subject. (Of course, there will be more.)

Große Fuge for String Quartet in B flat major op. 133 (Arr. for String Orchestra)

The conductor Felix Weingartner, Gustav Mahler’s successor at the Vienna Opera, made an arrangement of the fugue for string orchestra. Unlike Mahler’s Beethoven adaptations, this was warmly received and widely performed by leading conductors, who used it to show off the cohesive quality of their string sections. It became a trademark piece for Wilhelm Furtwängler, who recorded it with Europe’s two premier philharmonic orchestras, Berlin (1952) and Vienna (1954). Both have edge-of-the-seat tension. Furtwängler invests each phrase in the fugue with a life-or-death question. Do we deserve to survive after the horrors we have witnessed? If so, how? There is no decisive resolution. In the end, as in spectator sports, it is the performance we are left to admire, not the result.

No-one performed this score like Furtwängler. When his Berlin successor Herbert von Karajan attempted it in 1971, he took three minutes longer and sacrificed existential meaning to a wash of chocolate-box beauty. At around the one-minute mark, I was close to throwing up. Don’t take my word for it: listen here.

Let it be a better year.

From the Lebrecht Album of the Week:

So much nonsense is being spouted these days about ‘decolonising’ western music that we’ve forgotten it’s not western at all. It’s southern and eastern, arising around the Mediterranean Sea and spreading upwards into the European continent by a process of conquest and cultural supremacism. Europe was successively colonised by the Greeks, the Romans, the Mongols and the Arabs before it ever thought of spreading ‘civilisation’ to other parts of the world.

This new release is a blessed relief from the deconolising agenda….

Read on here.

And here.

In French here.

In Czech here.

In Spanish here.

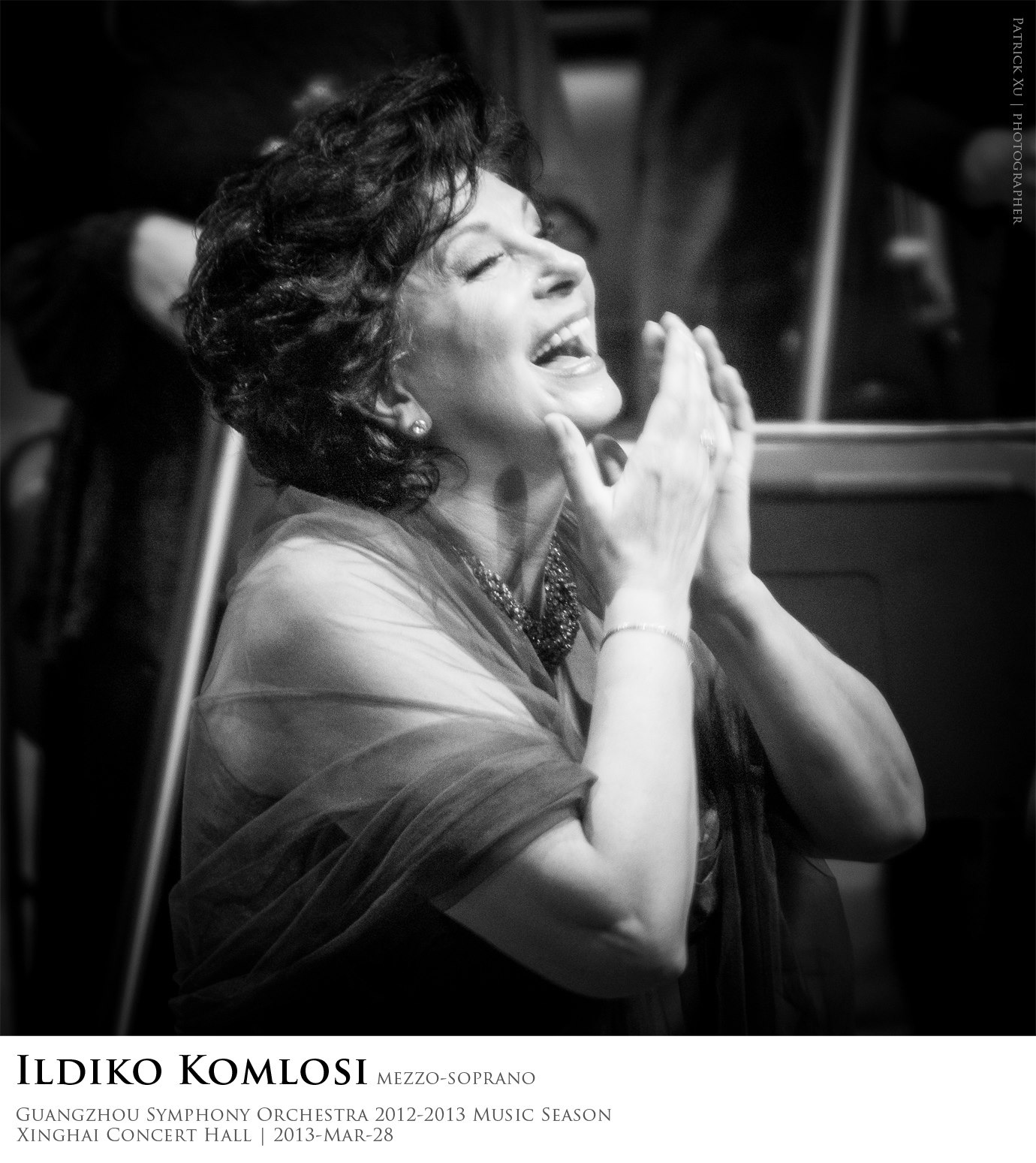

With Netrebko under hospital care Russia, we now hear that the Hungarian soprano Ildiko Komlosi tested positive for Covid-19 test on Monday and was rushed to hospital in an ambulance the following day.

Admitted to intensive care, she avoided being put on a ventilator and has now been sent home. ‘It is certainly one of the worst diseases of my life,’ she says, ‘but I will recover, we will recover!’

The Bayreuth boss was due to stage Lohenrin in November.

She has been told they’ll make do with an old productuion, shortened for Covid purposes.

The Berlin Phil have adjusted their season to the new normal.

In line with the new hygiene concept introduced by the Berlin Senate in September, from 1 November the audience will be seated in a “chessboard pattern” with a maximum of 1000 occupied seats in the main auditorium of the Philharmonie Berlin and 567 seats in the Chamber Music Hall of the Philharmonie Berlin. It will be mandatory to wear a mouth and nose covering during the whole concert. The hygiene rules also stipulate that concerts in the Philharmonie will continue to be played without an interval and last a maximum of 90 minutes.

Grange Park Opera is filming Owen Wingrave, Britten-s made-for-TV 1971 opera, in haunted houses in Surrey and London.

Grange Park Opera CEO Wasfi Kani says: ‘The opera requires a dozen interiors, which are well-nigh impossible to achieve on a theatre stage. However, filmed on location, we can have the Wingraves living in a real house, playing out their poisonous squabbles. In addition to its being an expression of Britten’s own pacifism, he was also reported as saying Owen Wingrave was partly a response to the Vietnam War. We are setting our production in 2001 on the brink of the war with Afghanistan which disgusts Owen, but inflames his spinster

aunt – played by Wagnerian soprano Susan Bullock.’

Spooky.

The conductor Mirga Gražinté-Tyla has been delivered of a second child in Salzburg, a boy, exactly two years after her first.

All are doing well.

The Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg is projecting ultra-violet rails onto its escalator rails to make them Covid-proof.

‘Germs are rendered harmless with this technology, which reduces smear infections to an absolute minimum,’ a spokesman said.

The device has been patented by a firm in Cologne.