What Beethoven did to the movies

mainWelcome to the 97th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

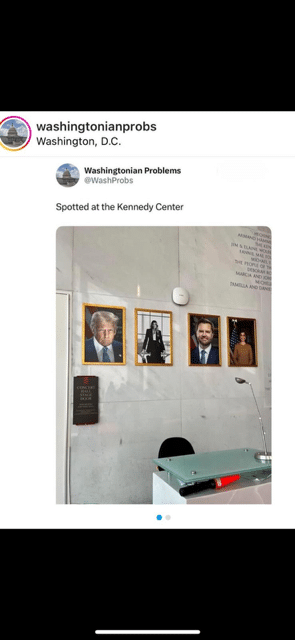

The conductor Sir Georg Solti once told me, ‘I am conducting Beethoven for a Hollywood movie. It will bring many young people to concerts.’

Some hopes.

The film was Immortal Beloved (1994), starring Gary Oldman as the great composer and the Dutch actor Jeroen Krabbé as his faithful amanuensis Anton Schindler, setting out on a posthumous mission to track down the one woman Beethoven really loved. Schindler decides in the end that Beethoven was consumed by love for his brother’s wife, the loose-living Johanna, a conclusion unsupported by any historical evidence and actively contradicted by Beethoven’s remorseless court fight with Johanna over the custody of her son Karl. The film never achieved international release.

Other musicians who can be heard on the soundtrack include Gidon Kremer, Murray Perahia and the London Symphony Orchestra.

In 2006, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer released Copying Beethoven by the Polish director Agnieszka Holland, shot mostly in Hungary. It finds the great man composing his ninth symphony with help from a young female copyist. Beethoven’s two copyists at the time were decidedly male. Ed Harris played the composer. The film proved ephemeral. The Kecskeméti Orchestra and the LSO are credited for soundtrack.

Although Hollywood has made numerous biopics about artists and writers, composers get shortchanged and Beethoven is elusive on screen. His greatest impact has been as a St Bernard dog in a children’s film franchise that has so far yielded eight movies, none of which utilise Beethoven’s music.

His works are most often heard in films about classical musicians, such as Hilary and Jackie (1998) where the Archduke Trio was performed and Mr. Hollands Opus (1995) where the 7th symphony was used to good effect (the full soundtrack was compiled by Michael Kamen; the orchestra was the Seattle Symphony).

Music relevance is immaterial. Für Elise made an appearance in Polanski’s 1968 horror film Rosemary’s Baby, the ninth symphony showed up in Die Hard (1998) and the string quartet Opus 18, No. 5 underscored Daddy Day Care (2003). There is an undercurrent of the Eroica Symphony in Mission Impossible (2015). What’s it doing there? It’s music, and it’s out of copyright.

That said, there are a few movies where Beethoven’s music is absolutely fit for purpose – the Emperor concerto in The King’s Speech (2010) where it is used to cure the King’s stutter; the first cello sonata in The Horse Whisperer (1998); and the first piano sonata in the haunting Warsaw film, The Zookeeper’s Wife (2017).

Among all his film credits, Beethoven looms largest in Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s novel, A Clockwork Orange. The central character, Alex, psyches himself up to commit rape and murder by listening to Beethoven’s ninth symphony, the humane antithesis to his violent actions. The recording used in the film is Ferenc Fricsay’s 1957 Berlin performance for Deutsche Grammophon.

Although Kubrick was knowledgeable about music and discriminating in his tastes, nothing about this film makes musical sense. Alex and his gang are thugs who threaten social order by feasting on the greatest masterpiece of western civilisation. Once arrested, Alex is subjected to behavioural conditioning, a form of mental torture not far removed from the psychiatric ‘treatment’ meted to dissidents in the Soviet Union. In the end, the gangmaster loses his violent urges and is rehabilitated by the music that first corrupted him.

Kubrick also used two Rossini overtures, William Tell and The Thieving Magpie, and selections from Elgar, Purcell and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade that were electronically warped on a Moog synthesiser by Wendy Carlos. Burgess proclaimed the film ‘brilliant’, an accolade he later retracted. Carlos released a separate album of his adaptations. Seen half a century later, the film’s mindless violence has lost some of its shock value but none of its unsettling threat. It’s an ugly film, unforgettable for all the wrong reasons.

What does it have to do with Beethoven? More than first meets the ear. Anthony Burgess, an indefatigable English writer whose real name was John Wilson, was himself a composer who completed three symhonies and structured some of his novels in sonata form. One of these was a recreation of Napoleon’s life, modelled on Beethoven’s Eroica and titled Napoleon Symphony: A Novel in Four Movements. Kubrick toyed for a while with making it into a movie.

The two creators got on well. They were conjoined by admiration for Beethoven’s inner rage, his hatred of oppression, his essentially revolutionary character. Although Alex does not articulate the attraction, one can appreciate how a young man alienated by the British class system might possibly turn to Beethoven as a hero – and how Beethoven suits his reckless nihilism.

In the novel, Alex describes Beethoven’s music pretty well: ‘‘Oh it was gorgeousness and gorgeosity made flesh. The trombones crunched redgold under my bed, and behind my Gulliver the trumpets three-wise silverflamed, and there by the door the timps rolling through my guts and out again crunched like candy thunder. Oh, it was wonder of wonders. And then, a bird of like rarest spun heavenmetal, or like silvery wine flowing in a spaceship, gravity all nonsense now, came the violin solo above all the other strings, and those strings were like a cage of silk round my bed. The flute and oboe bored, like worms of like platinum, into the thick toffee gold and silver. I was in such bliss, my brothers.’

Alex grasps Beethoven as an alternative to oppressive mass culture, the ‘twanging nonsense’ of pop music, foisted on young people ‘by middle-aged entrepreneurs and exploiters who should know better’. Alex understands that musical trash is inflicted by the haves to keep the have-nots under control. Beethoven is Alex’s freedom cry. A Clockwork Orange is not as amoral as it seems. In a world where mass culture thrives on state-sponsored musical ignorance, Beethoven has the power to raise deprived people above their miserable situation. Seen in this light, Beethoven is an eternal liberator.

Comments