Why auditions fail (and the NY Times is so wrong)

mainMax Raimi of the Chicago Symphony takes issue with the New York Times’s demand to abolish blind auditions:

To promote greater diversity in our symphony orchestras, The New York Times’ chief classical music critic Anthony Tommasini proposes that auditions should no longer be held behind a screen. Here is an excerpt from his article: “Blind auditions are based on an appealing premise of pure meritocracy: An orchestra should be built from the very best players, period. But ask anyone in the field, and you’ll learn that over the past century of increasingly professionalized training, there has come to be remarkably little difference between players at the top tier. There is an athletic component to playing an instrument, and as with sprinters, gymnasts and tennis pros, the basic level of technical skill among American instrumentalists has steadily risen. A typical orchestral audition might end up attracting dozens of people who are essentially indistinguishable in their musicianship and technique.”

“Ask anyone”? Nobody asked me. I play viola in the Chicago Symphony. A significant percentage, very possibly a majority of our auditions, end up with us failing to hire a musician. I am currently on the audition committee to find a new Principal Viola. We have had two rounds of auditions—prelims, semis, and finals—and have heard well over 100 candidates. We even tried out two of the more promising players, having them play a few concerts as Principal. The committee and our Music Director, Riccardo Muti, have been in agreement that none of the candidates meet our standards. Mr. Tommasini’s premise, that there is any number of more-or-less interchangeable candidates who can fill the openings in our major orchestras and the decision of which of them to select is essentially arbitrary is a fantasy. Unfortunately, once the pandemic allows it, we will again be back at square one, sitting for hours and days on end listening to one violist after another play Strauss orchestral excerpts.

The statement I cited was troubling for another reason as well. Mr. Tommasini talks about the “athletic component to playing an instrument”, comparing us to “sprinters, gymnasts and tennis pros”. Fair enough. But then, in a splendid sleight-of-hand, he talks about “dozens of people who are essentially indistinguishable in their musicianship and technique.” Disingenuously, he inserts “musicianship” into it; this has no parallel in his athletic metaphor.

Many years ago, our former Music Director here in Chicago, Daniel Barenboim, insisted that we have violists play the opening of the solo viola part to Mozart’s “Sinfonia Concertante” at auditions. It is not at all technically demanding. But I was astonished at how after six measures—perhaps twelve seconds of music—I knew everything I needed to know about whomever I was listening to.

The viola in this passage, in octaves with a solo violin, rises an octave on E Flats, the lower one a grace note, the upper one held for more than two bars that call for a crescendo and then a diminuendo. The music then meanders down the E Flat major scale, taking a scenic route with brief digressions. At first, the soloists are all but inaudible, lost in the sympathetic vibrations of the E Flats in the orchestra. Miraculously, at some point in the crescendo, we become aware of the soloists. It is as if they have always been there, since the beginning of time, but we hadn’t noticed.

The violist, in a matter of seconds, must transform his or her sound from a shadow to a physical presence, and then contrive to sing the circuitous downward line in one uninterrupted phrase, lyrically and yet with utter simplicity. E flat is a notoriously hard key to play in tune. The music is sufficiently slow so that your sound and intonation are stripped naked; the passage comes off as either absolutely gorgeous or grotesquely flawed.

The reason that this little except works so well in auditions is because it crystalizes perfectly what we are looking for in a colleague. The technical command that Mr. Tommasini references is a given; our search goes far beyond this. What is required is a concept, a way to tell a story with sound, with phrasing, with dynamics, and with every other resource at our command. Mr. Tommasini would reduce the criteria by which we evaluate candidates for our orchestra to speed and accuracy; judging us as one might judge a stenographer. I find it quite frankly offensive.

An argument can be made that hiring musicians of color is of such importance for the place of orchestras in our society that it should perhaps be a higher priority than necessarily finding the best musician for every opening. If Mr. Tommasini wishes to make that argument, it is a discussion well worth having. But to say that there are so many people who can step into our major orchestras and perform at the highest level that it doesn’t matter which of several candidates get the job (so we might as well take the musician of color) is simply not true.

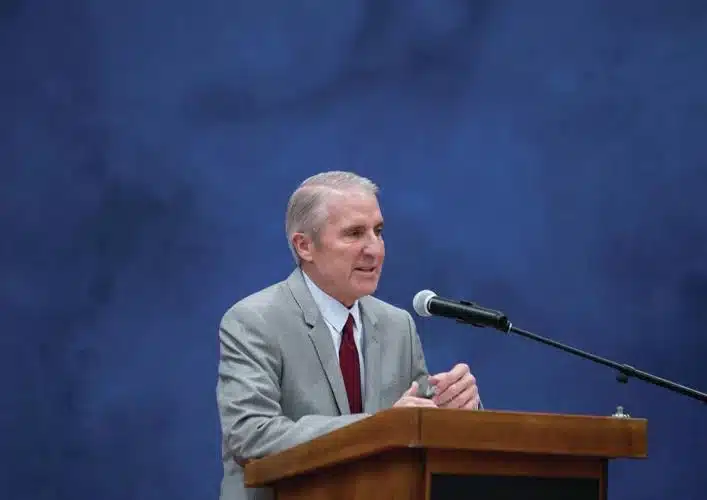

Max Raimi arguing it out with Bernard Haitink

Comments