You have now.

You have now.

Welcome to the 92nd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Beethoven: The 32 sonatas

The EMI producer Fred Gaisberg relates how box sets began:

It was given out that Schnabel would never stoop to recording, as he considered it impossible for a mere machine to reproduce the dynamics of his playing faithfully. Therefore, when I interviewed him he was coy but, all the same, prepared to put his theory to the test, though he would need a lot of convincing. At long last I was able to overcome all his prejudices. Tempted by a nice fat guarantee he eventually agreed that it was possible to reconcile his ideals with machinery…. on the sole condition that we must record all the piano sonatas and the five concertos of Beethoven complete.

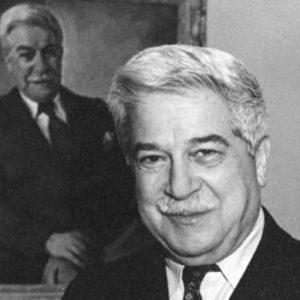

Schnabel is both a trial and a joy to his recorders…. I supervised every one of our twenty sessions per annum (!) over the next ten years and rate the experience of hearing his performances and listening to his inevitable impromptu lectures as a most liberal allowance of instruction combined with entertainment…. Before he came to London, Schnabel was only known as a Professor of Music at the Berlin Hochschule… He is a born pedagogue and never so happy as when he is seated at the piano, with his legs crossed, his left hand caressing the keyboard and his right gripping a choice cigar, and surrounded by a bevy of students, chiefly girls, who hang on to his every word.

Without any executive foresight, just the audacity of a pianist, the record industry brought the box set into being and found it more profitable, in its the long term, than the regular stream of individual releases. Schnabel had discovered that it was possible to commodify music by packaging it in sets – whether sonatas, concertos, symphonies or string quartets – and the industry never looked back.

Recording the sonatas between 1932 and 1939, Schnabel chose works in haphazard order, starting with opus 110, and proceeded in his own sweet way, with a splashing of wrong notes that he would not allow to be corrected. It is sometimes said that he did not care about errors, but that is not true. He refused to release two sonatas recorded for RCA that he felt were not up to standard. On the other hand, he felt it was essential to preserve evidence of the artist’s fallibility in order to make the record as much as possible like the live concert experience.

This tolerance of human error did not survive the arrival of stereo and high fidelity, when both artists and record labels strove to clean up their acts. By the 1960s, labels were lining up pianists to record ‘perfect’ Beethoven sets, the antithesis of Schnabel. Each, however, has its drawbacks along with its obvious merits. Daniel Barenboim‘s cycle for EMI is marred by the cockiness of youth and the haste of production. Barenboim, who had taken up conducting, already had too much else going on. He never forgave London critics for their harsh reviews.

Wilhelm Kempff on DG was unflappable, immaculate, often breathtakingly beautiful and overall too tightly controlled. The young Alfred Brendel, recording for Vox-Turnabout in early-1960s Vienna, was a breath of fresh air, working on a shoestring in snatched sessions and creating enough of a market with his releases for Philips to sign him to record the sonatas all over again – in sanitised circumstances, less gruelling and less gripping. Emil Gilels famously fell three sonatas short of completing his magnificent DG cycle. Claudio Arrau’s was the second set on Philips. The American Claude Frank joined the hustings, as did Rudolf Buchbinder and the Englishman Bernard Roberts.

Vladimir Ashkenazy recorded an underpowered set for Decca. Stephen Kovacevich covered the cycle for EMI from 1991 to 2002, too late in his career to recapture his initial zest. Richard Goode weighed in on Nonesuch, acclaimed by one critic as ‘a landmark’. Paul Lewis turned up on Harmonia Mundi and Jeno Jando on Naxos. Maurizio Pollini, who started out on DG in June 1975, finished his journey in 2014.

In the 21st century, we’ve had boxes or boxes-in-progress from Jean-Efflam Bavouzet on Chandos, Angela Hewitt on Hyperion, HJ Lim on EMI, Jonathan Biss on Orchid, Andrea Lucchesini very attractively on Brilliant Classics and, most discussed, Igor Levit on Sony. Each has a personal thumbprint and something new to say. The 32 works are susceptible to many shades of opinion and vary greatly when approached in youth and in senescence. If the above list of contenders appears exhausting one must nonetheless admire the persistence of the performers. Many august pianists declined to encompass the complete works.

Is there one box the covers all the bases? I am always engaged by Brendel’s Turanbout performances, there’s a perkiness and a chutzpah to his playing, alongside the gravitas that kicks in with the last sonatas. Arrau never lets you down, Lucchesini sparkles throughout and Ashkenazy is useful as a reference set, all the notes in place and no funny business going on between them. I am also impressed by the two slow developers Pollini and Biss; the thought each man invests in every sonata shines though in the execution.

But confine me to a single choice and it will have to be Schnabel. What I find irresistible is his unforced respect for Beethoven, untinged by fake reverence. He takes each sonata at face value but is not averse to finding quips and jokes in repeated phrases and to betray a glint in the eye as a pretty young woman crosses his eyeline. Schnabel sees Beethoven as a man like himself, less well mannered and quite useless in managing his affairs, but an overarching genius with all-too-human weaknesses, someone any of us can understand.

In that understanding, no-one surpasses Arthur Schnabel. Of all the great Beethoven pianists, he’s the one I would most like to have lunched.

I lost count. But by then I was in a trance.

Northern Lights Music Festival in Minnesota is staging Tosca outdoors this weekend – Saturday in Virginia and Sunday in Chisholm, continuing through July 26.

‘Probably the first opera performed live with an audience present in the U.S. since lockdown,’ said John Allison, editor of Opera magazine.

Read on here.

From the director Veda Zuponcic:

Stevie Zubich just picked up the Albin Zaverl Exhibit “Memories of the Homeland”, paintings of the “old country”–Slovenia from the St. Louis County Historical Society. We have 20 paintings and will hang the exhibit at the B’nai Abraham Cultural Center, both in the lower lobby and some in the sanctuary since we have very limited seating there.

The Dvorak String bass Quintet is rehearsing across the street at the Holy Rosary Church: Zach Stachowski, Sara Rodriguez, Angela Krachtmer, TR Lewcun and Guilherme Ehrat Zils.

Tosca is being rehearsed in Veda Zuponcic Auditorium;

A rehearsal for Op 1 #1 with Chris Shin and Kolton Graf is just outside the lobby;

the Ghost Trio rehearses today with Iosif Feigelson, Alexander Markov and Edisher Savitski;

and, at 2:00 all the instrumentalist run over to the Chisholm Ampitheater for a rehearsal of the Festive Fourth concert–American in Paris and Overture to Candide.

Busy artistic bees here on the Range! (Who was that masked musician?!)

While England sinks, the Scottish Government has created a £10 million emergency relief fund to lift ‘the threat of insolvency’ from venues and companies that cannot pay their staff.

The Scottish culture secretary Fiona Hyslop said: ‘This dedicated fund will be a vital lifeline to help performing arts venues continue to weather the storm. We are also actively considering support for grassroots music venues.

‘We know the impact of this crisis will be long-term so ambitious action to support the future of these organisations, as well as our wider cultural infrastructure, is vital.

‘Our theatres and performing arts venues and the talented freelancers who work with them are an essential part of the fabric of Scotland’s culture and communities and promote our international reputation, and we are determined that they will survive and be able to thrive again.’

Royal Scottish National Chorus

In other developments, The Stage newspaper is discussing redundancy with its staff.

From the Lebrecht Album of the Week:

I am about to break another rule. When I confined myself to reviewing just one album of the week around 15 years ago, I declared there would be no three-star reviews. Three is a cop-out. If it’s a great or good record it deserves four or five. Anything else I will only write about if, weak as it is, there is something instructive about its failure.

So this week we have a three-star: why? Because it’s …. and he’s caught between two stools. ….

Read on here.

And here.

And here (in Czech).

And here (in Spanish).

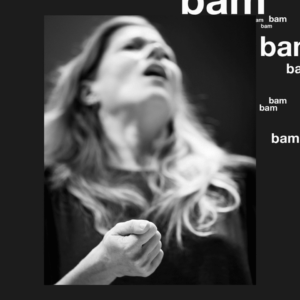

The livestream went down this morning, just as Barbara Hannigan popped up for an unnanounced solo in Mahler 4.

ACHTUNG!

Auf Grund von technischen Schwierigkeiten ist der Livestream im Moment unterbrochen. Sobald wir die Probleme gelöst haben, kommt auch der Stream wieder und ihr werdet die Möglichkeit bekommen, alle Kandidaten nochmals anzuschauen. Wir entschuldigen uns bei euch und hoffen ihr schaut nachher weiter!

URGENT!

Due to technical difficulties the livestream is currently unavailable. As soon as we have fixed the issues the Stream will be back and we will give you chance to re-watch everything you have missed. We sincerely apologise and hope you stick with us.

The surviving contestants are: Harry Ogg, Thomas Jung, Finnegan Downie Dear, Katharina Wincor and late qualifier Wilson Ng.

The excellent Roderick Cox has been added to the roster for the Barbiere revival in March.

Assuming the Met has reopened by then.

Roderick says: I am thrilled to announce my debut with the The Metropolitan Opera in Rossini’s Il Barbiere di Siviglia, March 2021. I adore this opera, and I am indeed honored and humbled to be able to perform it with two amazing casts next spring at the MET and San Francisco Opera. I just hope we are all able to return to the stage very soon and that our dear MET Orchestra Musicians may also return to work in January.

Every other European country has delivered a rescue package for shuttered institutions and frustrated artists. In London, the authorities keep promising and never delivering.

Why is that?

1 Low priority, although Boris (to my certain knowledge) personally understands the importance of the arts and backed them vociferously when he was Mayor of London. Gove, too, is a vigorous supporter.

2 Too much firefighting on other fronts – we do have the worst Covid record in Europe.

But critically:

3 There is no single person who can take the decision. Arts funding is nominally in the hands of Arts Council England, which needs approval from the Department of Culture Media and Sport, which passes the buck back to ACE, which kicks it up to DCMS… and so it goes.

I have argued for years against this pointless duplication of effort. Right now, it is literally killing the arts.

The Culture Secretary says he is working hard on a solution. In the interests of efficiency, he ought to be out of a job.

playing in Trafalgar Square, outside the DCMS

Malin Broman, concertmaster of Swedish Radio, got tired of having to deal with colleagues so she played all eight instruments in the chamber-music masterpiece.

Very fast and with great daring – especially the cello parts. For which she needs glasses.

Wuppertal has just named the Austrian Patrick Hahn as General Music Director of its opera and orchestra. He’s 24 and he starts work a year from now.

The agent is Jasper Parrott.

The greatest conductor of his generation was born on July 3, 1930 and died on July 13, 2004. He had retired ten years earlier and his wife had predeceased him by a few months.

Sad to acknowledge that in the 16 years since his passing no-one has come close to taking his place as a quirky, my-way, inspirational, anti-celebrity, musicbiz-averse, totally trustworthy and ever-surprising leader of musicians.

It’s starting to look as if we will never see his like again.