The ones who hate Beethoven

mainWelcome to the 83rd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Piano sonata no 25, ‘The Cuckoo’, opus 79 (1809)

Search the history of performing arts and you will find very persons of substance who express a strong aversion to Beethoven. There was Claude Debussy who, as a student, got up during a concert and said to a friend, ‘come on, let’s go, he’s starting to develop.’ But Debussy made disobliging remarks about most composers; he was just that type of musician. Few others echoed his detraction.

The misanthropic art critic John Ruskin wrote once in a letter that ‘Beethoven always sounds to me like the upsetting of a bag of nails, with here and there also a dropped hammer’. But this is such a fogeyish English view it can almost be taken as a compliment. It is not until Chuck Berry clamours ‘Roll over, Beethoven, and listen to the rhythm and blues’ that we encounter organised cultural resistance to Beethoven and the beginnings of a process that converts the great classics of music into a minority art form.

Beethoven, on the whole, stood for two centuries on a universal pedestal as one of the summits of human achievement. Friedrich Nietzsche, whose extremist views on race and sex did not occlude the validity of other ideas, wrote with great perception that ‘Beethoven is something that happens between an old crumbling soul which is constantly breaking up and a very young soul of the future which is constantly coming. In his music there is that half-light of eternal loss and of eternally indulgent hoping.’ This touches very close on Beethoven’s own treasured roots in a faded past and his undimmed aspirations for a better future.’

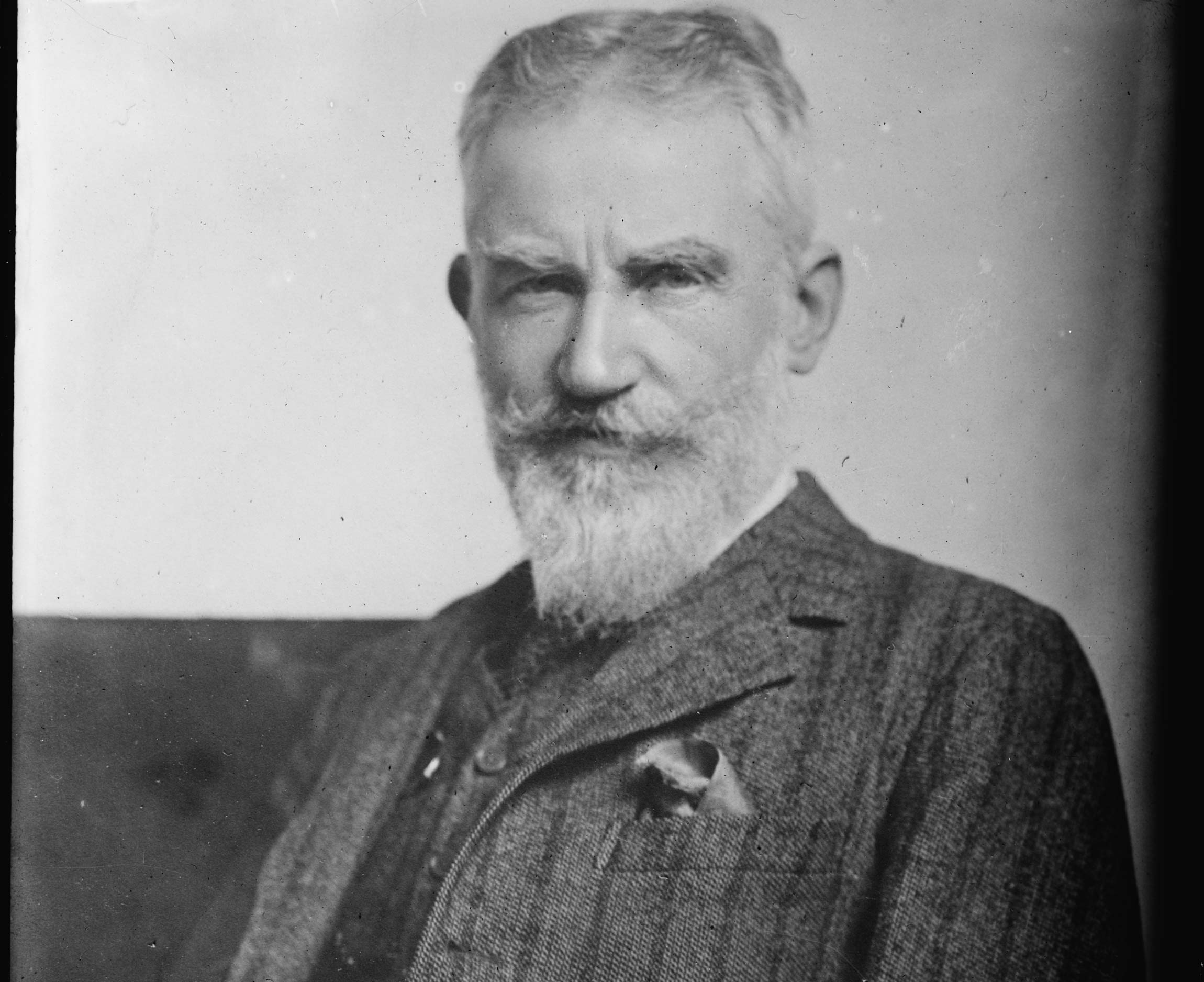

The Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw, brutally acerbic towards Brahms, wrote an article for Radio Times in March 1927 on the bicentennial of Beethoven’s death in which he over-confidently predicted that the new medium of broadcasting would earn Beethoven a mass audience for all time to come. Shaw explained Beethoven’s lasting relevance like this:

Now what Beethoven did, and what made some of his greatest contemporaries give him up as a madman with lucid intervals of clowning and bad taste, was that he used music altogether as a means of expressing moods, and completely threw over pattern designing as an end in itself. It is true that he used the old patterns all his life with dogged conservatism (another Sansculotte characteristic, by the way); but he imposed on them such an overwhelming charge of human energy and passion, including that highest passion which accompanies thought, and reduces the passion of the physical appetites to mere animalism, that he not only played Old Harry with their symmetry but often made it impossible to notice that there was any pattern at all beneath the storm of emotion. The Eroica Symphony begins by a pattern (borrowed from an overture which Mozart wrote when he was a boy), followed by a couple more very pretty patterns; but they are tremendously energized, and in the middle of the movement the patterns are torn up savagely; and Beethoven, from the point of view of the mere pattern musician, goes raving mad, hurling out terrible chords in which all the notes of the scale are sounded simultaneously, just because he feels like that, and wants you to feel like it.

And there you have the whole secret of Beethoven. He could design patterns with the best of them; he could write music whose beauty will last you all your life; he could take the driest sticks of themes and work them up so interestingly that you find something new in them at the hundredth hearing: in short, you can say of him all that you can say of the greatest pattern composers; but his diagnostic, the thing that marks him out from all the others, is his disturbing quality, his power of unsettling us and imposing his giant moods on us. Berlioz was very angry with an old French composer who expressed the discomfort Beethoven gave him by saying “J’aime la musique qui me berce,” “I like music that lulls me.” Beethoven’s is music that wakes you up; and the one mood in which you shrink from it is the mood in which you want to be let alone.

When you understand this you will advance beyond the eighteenth century and the old-fashioned dance band (jazz, by the way, is the old dance band Beethovenized), and understand not only Beethoven’s music, but what is deepest in post-Beethoven music as well.

Shaw was wrong on two counts: the mass audience and the urgent stimulus. There are many works like the Cuckoo Sonata that do nothing but lull. Why? We’ll never know. It last about ten minutes and unles the performer is exceptionally heavy-handed it leaves us mostly untouched in both the emotional and analytical parts of the brain. What did Beethoven have in his mind when he wrote it? Probably not much. There are quite a few works like the Cuckoo and we need them as light relief between the thunder and lightning of the unpredictable masterpieces.

Claudio Arrau‘s 1996 recording is unexceptionable. Andras Schiff’s (2006) would not be out of place in the lobby of a grand hotel. Igor Levit’s (2017) is so quick it’s over before you’ve sat down. Jonathan Biss (2015) takes it all too seriously. Maurizio Pollini (1989) frightens the horses. I’m not sure anyone does it lighter, quicker or wittier than the very first known recording, Arthur Schnabel’s in 1935. It will wake you up, gently.

Comments