Beethoven’s zero option concertos

mainWelcome to the 87th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

In addition to the five numbered piano concertos, sketches exist for two more. The larger outline was written when Beethoven was 13 or 14. After multiple revisions, he seems to have forgotten about it once he left home for Vienna, probably recognising that it was a few paces behind the leaders. The solo part is fully sketched and there are indications for orchestral accompaniment. The manuscript sits in the Berlin State Library, where a number of pianists have studied it prior to making recordings. Scholars duly accorded it the numeral zero, as if it were a respectable work in the catalogue.

Is it? Not really. The opening theme is like juvenile Mozart without the wit and sideswipes. Beethoven develops his little tune in a conventional fashion, as if he were preparing homework for his teacher, and the general effect is of a score by one of his less interesting contemporaries – Clementi or Dussek or even Czerny – note-spinning to no lasting purpose. The second movement gives hints of what might lie ahead in the C major and D major concertos, but the notes tickle the ear without gripping it. The whole work in its most augmented form lasts 23 minutes and you’d be hard-pressed to remember any of it an hour later. Mari Kodama gives an agreeable reading in 2019 with her husband, Kent Nagano, conducting the DSO-Berlin. Ronald Brautigam made a rather fuller orchestration for his 2008 recording on BIS, playing a period piano with massive flourish. There is also a recording by Howard Shelley that I have not been able to find.

The chief alternative to Kodama is Sophie-Mayuko Vetter, a Japanese-German pianist who is closely associated with Stockhausen-type modernism. Vetter plays a Beethoven-era Broadwood fortepiano and sounds fully committed to this material. She is accompanied by the Hamburg Symphony Orchestra, conducted a tad pedantically by Peter Ruzicka. She adds an intriguing world premiere of…

Beethoven Rondo for Piano and Orchestra in B-flat major B-flat major, WoO 6

This is another piano concerto fragment, published posthumously in 1829 with the solo part completed by Carl Czerny. The orchestration was reconstructed in 2018 by Nicholas Cook and Hermann Dechant. What catches the ear is a hint of the opening phrase of the future Emperor Concerto. Could that be possible? With Beethoven, everything’s possible. Vetter plays with panache and conviction.

Concerto for Pianoforte and Orchestra in D major op. 61a

After the chaotic premiere of Beethoven’s violin concerto, which was poorly received, Muzio Clementi asked if he could make a version for piano. Beethoven consented and the alternative version appeared in 1807. Beethoven was sufficiently enthused by Clementi’s effort to write a new cadenza for the first movement, involving plenty of percussion as well as solo piano.

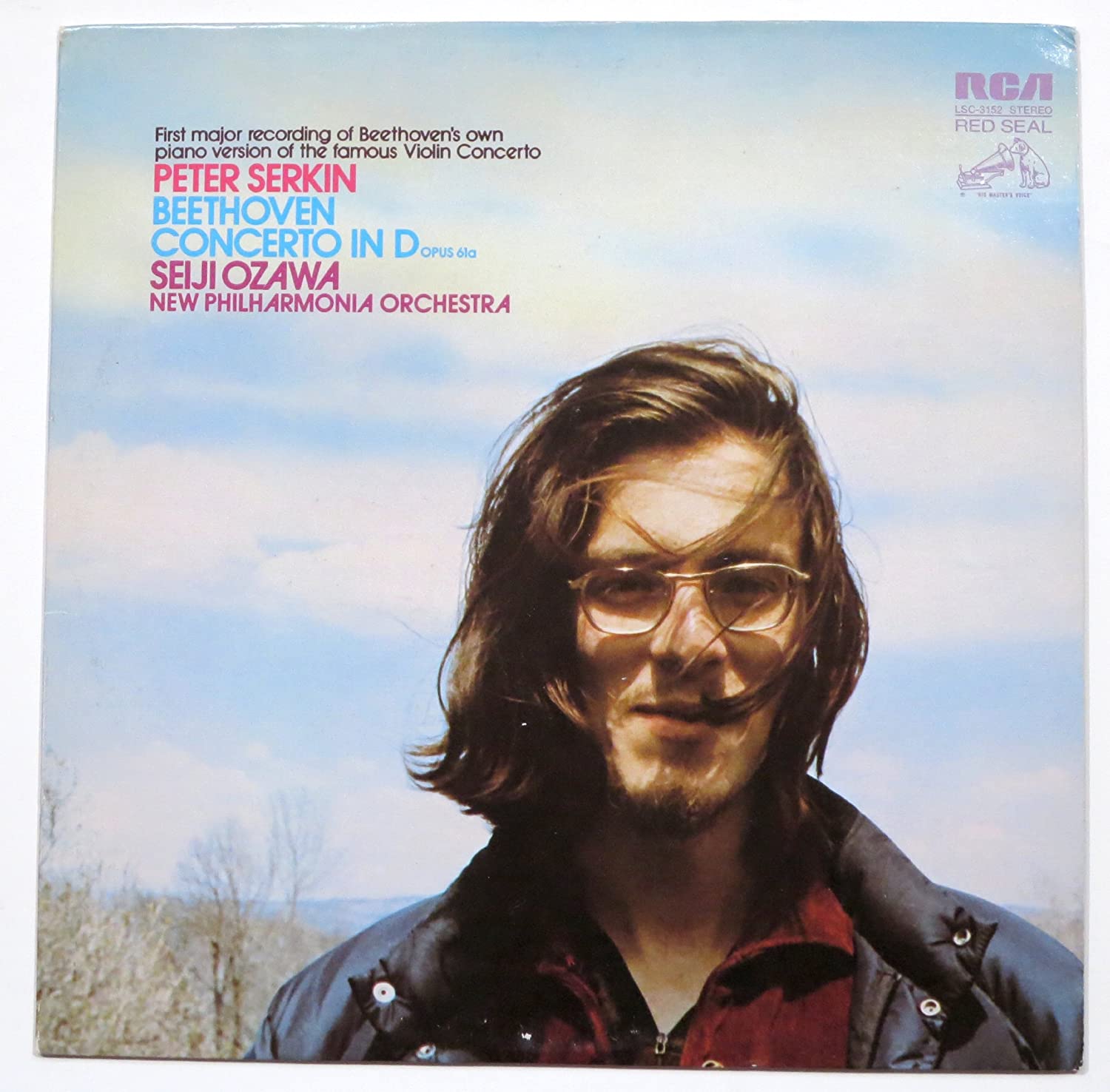

There have been a number of recordings, some of quirkish disposition. I rather like Peter Serkin in his hippie period playing the concerto with Seiji Ozawa and the New Philharmonia. The tempi are a bit sluggish and the orchestra is too far recessed for comfort, but Serkin gives the work a subversive twist, ambling his way into it as if he’s not sure whether he should be doing this square stuff at all, but growing to like it despite himself. Certainly, it is the least awkward of all the versions I have heard – and all of them leave me squirming to some extent since the towering existence of the violin concerto looms over anyone who attempts this ersatz piano swap.

An especially intriguing offering on Idagio is a 1954 Vienna performance by Helen Schnabel, Arthur’s daughter-in-law, and on this evidence a capable if not overly characterful keyboard artist. The orchestra is unnamed but the conductor is F Charles Adler, a pioneering Mahlerian, and his control of the proceedings makes this a worthwhile and immersive experience. There are moments of near-rapture in the adagio, which is more than we have a right to expect in a secondhand score. I’d like to hear more of Ms Schnabel.

Other contenders include the Finn Olli Mustonen, directing the Tapiola Sinfonietta with a heavyish hand, paying too much homage to the work’s reputation to make it credibly his own. The Frenchman Francois-René Duchable has a different problem with the Warsaw Sinfonia. His conductor is Yehudi Menuhin and no way is Yehudi going to let a pianist seize control of a summit of violin lore.

My first encounter with opus 61a was in Daniel Barenboim’s 1989 recording for DG with the London Philharmonic. I disliked it on first hearing and find even greater fault with it now. Barenboim conducts from the keyboard, reducing the solo part to little more than tinkling decoration and seriously undermining the balance of the work. Beethoven intended the violin to engage in mortal combat with the orchestra. Barenboim reduces the impact to that of a middling Mozart piano concerto, nothing grandiose about it.

Peter Serkin and Helen Schnabel are the ones to sample, secondary names of famous brands.

I rather like the version of the violin concerto that Pletnev arranged for clarinet. Works quite well.

Peter Serkin and Eugene Ormandy got into such a serious disagreement over op 61a in 1969 that Ormandy abruptly “fired” him the day before the concert in New York. The Philadelphia Orchestra cast about for another pianist who knew the piece and of course, none of the usual suspects did. I do not know what caused them to think of Gunnar Johansen, an Egon Petri pupil on the faculty of the University of Wisconsin, but he agreed to learn the piece on about 24 hours notice and played the concert, making headlines.

I was at that concert and thank you for relating the real story. The performance was unfortunately very weak beer as poor Johansen had his head deep in the score with predictably prosaic results.

The only version I’ve heard is the Barenboim. Made me think the whole idea was just a big fat failure. Maybe I should give some of these others a try…

As long as we’re talking about transcriptions, Dejan Lazic’s version of the Brahms Violin Concerto for piano is IMHO really quite good — very Brahmsian, much more than just a transcription of the violin line for the right hand.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dFsGPLScYM4

(There’s also a “real” recording with the Atlanta Symphony and Yoel Levi)

That is a brilliant transcription, rather a recomposition. I did not know it.

^ Sorry, I meant Robert Spano (self-forehead-slap)

https://www.amazon.com/Brahms-Piano-Concerto-Rhapsodies-Scherzo/dp/B003122H50

I have a “live” recording with Maurizio Pollini and Orchestra Sinfonica della RAI di Milano

Franco Caracciolo, conductor from June 6/1966. Good performance of course, after all it is Pollini; unfortunately the sound is awful and the overall feeling is rather one more of frustration than satisfaction.

Very hard-to-fynd, poor sound quality, it would be worth a “modern” remastering since Pollini did not do any commercial recording of this Concerto, and probably did not play it many times.

Discographic information: Op 61a with Maurizio Pollini and the RAI Symphony Orchestra of Milan conducted by Franco Caracciolo, recorded in Milan June 15, 1966. The recording, a radio broadcast, was included in a CD released in 1990 (The Classical Society, Italy, CSCD113). Op 61a was a “filler” to the “Emperor” Concerto op 73, with the RAI Symphony Orchestra of Rome conducted by Claudio Abbado, also a radio broadcast from 1967.

My CD has Concerto no4 op 58 as the main work; op 61a was also the second opus on the record.

==Barenboim’s 1989 recording for DG with the London Philharmonic.

It’s actually with ECO and is a bit earlier than 1989. I think that year just refers to the coupling with the Romances.

The “plenty of percussion” refers to timpani which is a major appearance in the cadenza

The very first Daniel Barenboim recording in about 1974, with the English Chamber Orchestra, also on DG, is superb. The quite small orchestra doesn’t diminish the scale of the piano (which is what I suspect the perceived problem is with the much larger LPO; sorry I can’t make a direct comparison, as I haven’t heard the later recording).

My teacher (who was playing in it) tells me that the Barenboim recording was actually in early 1973 and was a last-minute replacement for a scheduled recording of the Triple concerto with DB, Pinchas Zukerman and Jacqueline du Pré. Apparently the ECO had great difficulty with the pitch of the Steinway piano, which inexplicably was found to be tuned to A=444. Later in the session-time Zukerman recorded Vaughan Williams’ ‘The Lark Ascending’, pretty well in ‘one take’ so that they didn’t run into overtime.

A little clarification: On her superb contribution to the Beethoven festivities, Sophie-Mayuko Vetter does NOT play the “Rondo for Piano and Orchestra in B-flat major B-flat major, WoO 6” (or claims that this is a world premiere recording), she really premieres the “Piano Concerto (No. 6) in D Major, Hess 15 (Fragment)”, Completed N. Cook & H. Dechant

Here it is:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=inIs3WE-kok

A sketch which still needs to be worked upon.

In the early concerto, to me, the orchestral writing is unmistakably Beethoven with many characteristic tropes.

I have heard the standard violin version using the cadenza with tympani – done by the Boston Symphony. I believe C. Tetzlaff was the soloist.

W. Schneiderhan was the first to record the Violin Concerto – with BPO/Jochum – playing the cadenzas written for the pianoforte transcription. It was, incidentally, the first DG stereo LP to appear in the UK without a mono equivalent.

The most interesting thing about the piano transcription is the cadenza with kettledrums that envious violinists have re-transcribed back into their concerto, particularly Schneiderhan. It’s not a patch on Schnittke’s. Otherwise, an interesting curiosity that doesn’t quite work for me, but certainly worth hearing and knowing.

Try to hear Busoni’s cadenza, recorded by Szigeti in stereo on Mercury (a very wobbly Szigeti alas) and by Ricci on his Biddulph CD where he records all sorts of cadenzas plus the concerto itself. It shares with Beethoven and Schnittke the notion that others in the tutti join in with the violinist.

Busoni’s cadenza for the Brahms Violin Concerto (recorded recently by Isabelle Faust) has timps and strings along the way.

That’s news to me, Microwave. Is there also a chorus singing “Funiculi, funicula” as in Busoni’s monster piano concerto?? Ricci must have missed this one in his dictionary of Brahms violin concerto cadenzas as I don’t recall it.Forgive me, Macroview. No, doggone it, he’s someone else. Microview, then. Small m. There!

Hi Edgar,

Despite being a lapsed timpanist myself, I must say that I never liked that re-purposed cadenza with timps grafted onto the violin concerto. I’m embarrassed to admit that I had not realized it was Beethoven’s own invention before reading the above article.

Worth hearing: yes. Once.

(But I don’t like the op. 61a anyway; I’m an op. 61 guy all the way.)

BTW – If you happen to be a father, Edgar: Happy Father’s Day!

Greg Bottini — Saoristi! You know, Greg, the very first time I read one of your posts, I thought, “Now this is an Op. 61 guy, not a 61a. It’s something to do with Italian shoe sies, I’m sure o it. Certo.. Same thing for Op. 81a and 81b where you and Luca had a friendly difference of opinion about Brendel’s “Les Adieux” Me, I’m all for the Op.81b wind sextet and those tricky horn parts.

But you are ex-timps? That explains the sensitivity to brash kettle-drums in Mahler. Reiner and Rattle aslso are ex-timps. Hmm.

And I see David Nelson has answered my errant question about Ricci and the Busoni cadenza, as usual. Thanks, David, and microbrew. I don’t likeit either but wasn’t about to say so with vulpine eyes ready to pounce.

Buona sera, Edgar….

Yes, it must be the shoe sizes!

Amico mio, I don’t like to think of my humble self as “ex-timps”. Once one is a drummer, one is ALWAYS a drummer. I prefer the term “lapsed drummer/timpanist” when referring to myself.

I certainly don’t mind “brash kettledrums”, as you put it, but only when the situation calls for them.

Long ago, I heard or read that someone (perhaps Monteux?) referred to timpani and percussion as the seasonings of the orchestra.

As an enthusiastic home chef, I agree with this wholeheartedly!

You make a spicy Texas-style chili, you throw on the chile powder and cayenne, and molto aglio! But you make a subtle sautee of chicken breast, you’re MUCH more circumspect in your seasoning.

Capisce?

The reason I mentioned the too-prominent timpani in that Horenstein Mahler 3 is that they stuck out like a clove of raw garlic in a consomme.

I knew that Rattle is a percussionist, but I was unaware that Reiner was. Really? That might explain the great “grooves” Fritz achieved in works like the Music for Stringed Instruments, Percussion, and Celeste, Lt. Kije, and Scheherazade.

FYI: the famous TV chef Emeril Lagasse is a percussionist, and actually received a scholarship to study at the New England Conservatory.

He turned it down, though, to attend cooking school. Kickin’ it up a notch!

Howard Shelley’s recordingss of both WoO4 and the violin concerto transcription are excellent.

Surely the B-flat major Rondo Woo 6 is reasonably well known? Before van shelved it, it had been the original finale for concerto op. 19 in same key.

As to recent con ertante Piano chunks, there is the Nicolas Cooke/Hermann Dechant completion of a late fragment, Hess 15

I believe Boris Giltburg’s Naxos recording with the Rondo has the latter in its original complete form (Gramophone podcast is available online on Giltburg in Nos 1 and 2)

The vl/pf concerto has a rather unsatisfying solo part, the textures for the solo piano don’t really work that well as in the works envisioned as a piano concerto. It works really much better as a violin concerto – the musical idea, the vision, was so strongly defined as music for the violin.

Beethoven’s juvenile piano concertoin E-flat and fragment make little impression. Didn’t another orchestrate them, like Chopin’s “third” Allegro di Concerto” that that Arrau played in the solo ersion that Chopin wrote his father about? Likewise the two large choral works, fascinating attempts showing where Beethoven started and developed from, but impressive for a boyt his age.

the Beethoven juvenilia I like are three “Elector” piano sonatas Gilels played, and three piano quartets, parts of which he used in later works.

Clarinetist Michael Collins performs a version of the D major concerto for clarinet and orchestra with the Russian National Orchestra – it is on Youtube.