Beethoven can’t get this tune out of his head

mainWelcome to the 82nd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Piano sonata no 24, A Thérèse, opus 78 (1809)

The second movement of this short sonata, written for one of his pupils, bears an uncanny similarity to ‘Rule, Britannia!’ on which Beethoven had written an entertaining set of variations. Why it should pop into his mind at this juncture, when he may have been in love with his pupil Therese Countess von Brunsvik (or, more likely, her sister Josephine) is one of those unfathomable mysteries that are not worth pursuing.

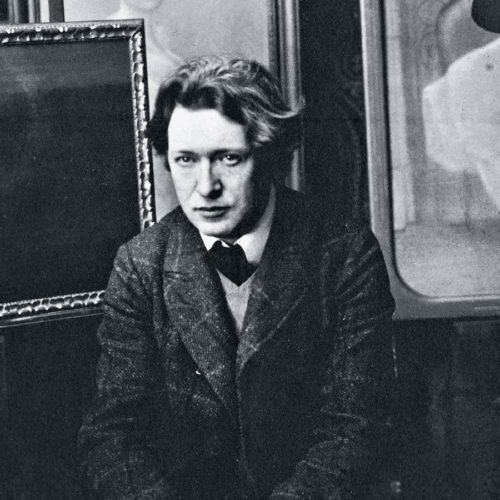

The phenomenal pianist and composer Ferrucio Busoni wrote somewhere that it’s the duty of an interpreter to rescue a work of Beethoven’s when it falls from ‘sublime heights’. Making this seven-minute sonata sound smarter than it really is represents a challenge to all pianists who have ever attempted it. Worth the effort? Always.

Busoni has another insight into the composer he admired above all others, albeit with a composer’s objective distance. Beethoven,’ he writes, ‘is a master only of psychological tragedy; the tragedy of a situation [involoving two persons] is quite dull within him, whereas psychological tragedy unfolds itself within a single person.’ This is serious and profound: Beethoven might dedicate a sonata to a love-object, but the struggle of the work is raging only within himself. Busoni went on to say elsewhere: ‘In the most tragic situation, (Beeethoven) is ready with a joke—in the most hilarious, he is capable of a learned frown.’ How I wish Busoni would have composed variations on Beethoven themes in the way that he did for Bach.

Many pianists have theorised about Beethoven’s state of mind from the intimate perspective of assimilating his 32 sonatas into their own hands and minds. Arthur Schnabel, who plays this sonata as if he can’t wait to be rid of it, was prone to floating theories about Beethoven while Alfred Brendel, who published his own theories about Schnabel and Beethoven, treats this sonata as a bit of fluff, not one that reveals much about Beethoven’s mind. There are now books and essays being published about Brendel’s thoughts on Schnabel, Busoni and Beethoven. It just goes round and round, with very little relevance for the listener who would like to find feeling and meaning in a sonata.

The one pianist who communicates with clarity about Beethoven is the Canadian Glenn Gould, in a 1967 pre-concert talk:

Beethoven is a kind of living metaphor for the creative condition. In part he is the man who respects the past, who honours the traditions [from] which art develops, and while never other than intense and constantly gesticulating with those rather violent gestures which are so peculiarly his own, this side of his character leads him to smooth off the edges of his structure sometimes, to be watchful and even painstaking on occasion about the grammar of his musical syntax.

And then there’s this other side, the fantastical romantic side of Beethoven, which draws from him those unapologetically wrongheaded gestures, those proud, nose-thumbing anti-grammatical moments which, in the context of tradition [and] against the smooth and polished edges of classical architecture, make him unique among composers for the sheer devil-may-careness of his manner. But in the end this sort of amalgam exists for every artist, really; within every creative person there is an inventor at odds with a museum-curator.

Absolutely nailed it. So does Gould’s interpretation (1975) of the 24th sonata live up to his dazzling conclusions? In part (as Gould might have said) it fulfils Beethoven’s vision and then some. Gould, with his quirky genius for internalising everything he plays, makes the opening movement sound like a George Martin arpeggio to a Beatles pop song and the second half like a stretch of crazy paving. After you’ve heard Gould’s Theresian adumbrations, you won’t listen to another Beethoven interpreter all week. He’s in a class of his own, like it or not.

The closest any pianist came to Gould was the Austrian Friedrich Gulda (1958), but his mind was so quicksilver he starts to sound bored halfway through the opening movement and the listener never really recovers from the insult. Among other great minds that addressed this sonata, Rudolf Serkin (1948) falls asleep in the opening movement, recovers with a jerk and gets through the finale in a world record time of under two and a half minutes. Wilhelm Kempff (1965) is, as you’d expect, punctual, immaculate and inoffensive. One modern interpreter has a way of his own with the work – the Turkish pianist Fazil Say (2019), an artist who spent must of the past decade under threat of arrest for blasphemy by a fundamentalist Moslem regime in a former European democracy. Beethoven seems to have special meaning for Fazil Say.

For reasons known only to himself, and probably no more than convenience, Beethoven wrote piano sonatas in clusters. The 24th (opus 78) is followed in rapid succession by the 25th (‘Cuckoo’ opus 79) and the 26th (‘Les Adieux’, opus 81a). At this point in his life, he has got the art of sonata making down to a piece of craftsmanship, even a chore. Each is top-drawer Beethoven. We cannot yet see how he advances from these estimable productions to the astonishing heights of the five last sonatas.

I suppose that is why we keep going back to these middling sonatas, to see if the composer leaves any clues to his next leap. I am not going to draw any giant Brendelian inferences of interpretation, but before you leave this post take a listen to Heinrich Neuhaus (1888-1964), pupil of Scriabin and teacher of the two greatest Russian Beethoven pianists, Sviatoslav Richter and Emil Gilels. Neuhaus exists in a detached time frame and sound world, making us listen not so much to Beethoven as to what Beethoven might mean at the moment we are listening. He actually requires the listener, like a psychoanalytic patient, to put in some work on him or herself and then ask whether this composer and this work might possibly change our lives. Neuhaus knows.

Comments