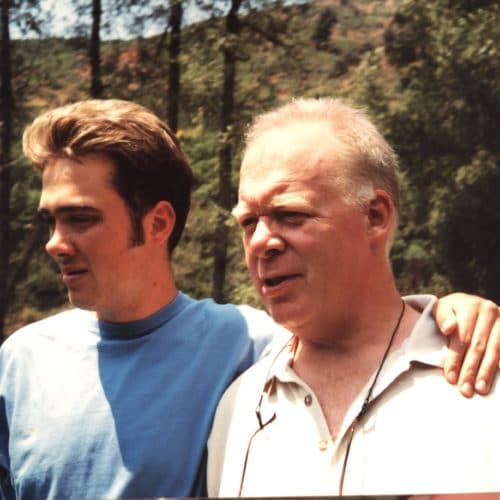

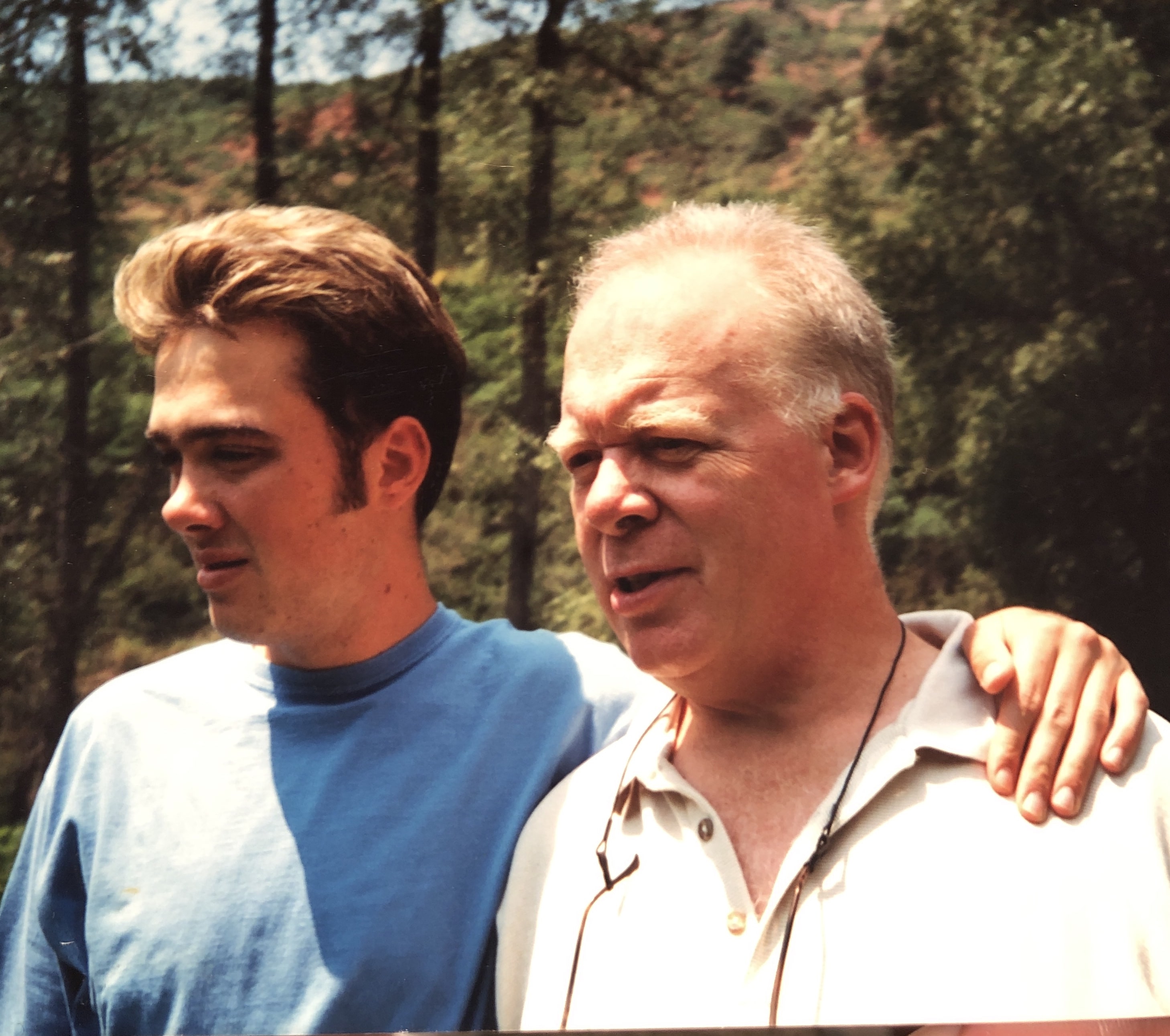

Lynn Harrell’s son: My father never stopped reaching out

mainEben Harrell has shared with us his reminiscences of a marvellous, multi-skilled Dad.

I am sitting on the banks of a high-mountain creek in Southwest Colorado trying to conjure my father, the cellist Lynn Harrell, who died this week at age 76. The water is high from the spring run-off and I do not know if I will find much clarity. But as I approached the banks and heard the water-music build in intensity, I knew I had come to the right spot.

My father loved to fish these alpine streams. He shared that passion with me in the summers when I would follow him to Colorado for the Aspen Music Festival, where he was a mainstay for many years. My father was an incredibly talented man—perhaps the finest cellist of his generation, he was also, at times, a 4.5 USTA-rated tennis player, a single handicap golfer (despite taking up the game as an adult) and a 1800 Elo-rated chess player. Yet he was an enthusiastic but quite ineffectual fly-fisherman. He fished because he enjoyed the poetics of dry-fly fishing—the umbilical connection to nature that a fly-line provided, and the magic of summoning wild trout from the depths simply by dancing shadows across a river’s surface.

We spoke often about the powerful ending to Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It, in which the author–an old man alone on the river—uses the rhythm of fly-casting and poetry to try to summon memories of lost loved ones. “Now nearly all those I loved and did not understand when I was young are dead,” Maclean writes, pausing a beat to let the power of his line gather behind him. “But I still reach out to them.”

My father never stopped reaching out. It is what made him such a great musician. In middle age he came to realize how playing the cello was, in part, an attempt to cross a bridge to his own deceased musician parents, particularly his father, a great singer who died when Lynn was still a teenager. He chose the cello as his instrument, he later realized, because of its proximity in range and expression to his father’s voice, and also the posture of its player, which is one of embrace. He obsessively listened to his father’s recordings and spent hours in his practice room honing his technique in the hope of recreating his father’s sound. Among instrumentalists he perhaps came closest to achieving a singing quality in his playing, but in his dark moments he knew his parents remained forever beyond his grasp. Yet he persevered; he was simultaneously comforted, compelled and haunted by the quest. Audiences around the world are richer for it.

This sounds depressing, but I believe it is the opposite. It is life-affirming. Like any great artist, my father understood that art is the only way (perhaps other than religion) to reconcile life’s most tragic elements. It offers moments—just moments—of transcendence. This is why even the most ravaged dementia or amnesia patient can hum their way through a melody without losing their way. T.S. Eliot wrote of “music that is heard so deeply/ that it is not heard at all, but you are the music, while the music lasts.”

There’s a memory I have of my father’s playing when I was a child. It’s one of the first memories. I was ill in bed with a fever. Someone (my mother?) put on my father’s recording of Bach’s cello suites. The Bach suites were written from the inspiration found through one man’s relationship with God. They are meditative, devout, at times exultant in their attempts to summon a celestial harmony. In my feverish state, I remember thinking that my father was actually in the room with me, talking to me, soothing me. When I listened to them in later years as an adult, Bach’s efforts to communicate a strong, out-of-body euphoria, the scales that unfold like a ladder dropped down from heaven, take me back to that night as a child, when I felt my father’s presence in an empty room.

A warm, emotive man with an impish sense of humor and an easy, booming laugh, my father was easy to love. But he was never great at human relationships, and he could hurt people close to him. When I was twenty he divorced my mother and threw himself into a new marriage. When they had two kids, his attention turned to building a new life with them, and he abandoned almost all his previous friends in favor of a new social circle, which I never understood and, if I’m honest, never truly forgave. It was a great paradox at the heart of the man: when he was with you, he was so totally present, but then he could disappear, sometimes forever. I am sometimes haunted by the critic George Steiner’s warning that the student of art “may begin to hear the shouts in the poem louder than the shouts in the street.”

I do not write about this side of my father in bitterness or acrimony. Some of the people once close to my father feel aggrieved. But many feel as I do: grateful for the time with a flawed but incredible artist. My father once told me that when my grandfather Mack Harrell sung Bach’s Cantata, “Ich Habe Genug,” he insisted that program notes not contain the traditional translation—“I am fulfilled” but rather “I ask for no more.”

For many years now, even when we saw one another only once or twice a year, my father’s recordings have been the connective tissue that kept us close. So it will continue to be. His playing is how I want to remember him. Befitting the instrument itself, much of the cello’s greatest repertoire has mourning at its core. I think of the longing melodies of Dvorak’s cello concerto, written with great homesickness after Dvorak moved to America, or the arpeggios—the broken chords–that open the Elgar concerto, perhaps the most profoundly sad opening to any work of art. (“If you want to feel the tragedy of World War I,” my father once told me in one of our long, unforgettable discussions about music, “Listen to the opening bars of the Elgar. An entire society cracked apart, the scalding sadness and cumulative regret of so many lives cut short. It’s all there in just a few opening notes.”)

And so it is.

The challenge for the cellist wishing to master this aspect of the repertoire is to be defiantly mournful—to earn redemption from the heartbreak by showing the audience the beauty inherent in loss. Through the power and physicality of his playing, his near flawless technique, and the singing, human quality of his sound, I believe my father delivered this transcendence in his recordings and performances.

As a child one of my favorite pieces that my father played was Schubert’s An Die Musik, a song also sung by my grandfather. My father read the lyrics at my wedding four years ago.

‘Du holde Kunst, in wieviel grauen Stunden,

Wo mich des Lebens wilder Kreis umstrickt,

Hast du mein Herz zu warmer Lieb entzunden,

Hast mich in eine bessre Welt entrückt!”

“O sublime art, in how many bleak hours,

When the wild tumult of life ensnared me,

Have you kindled my heart to warm love,

Have you carried me away to a better world!”

I have just started the process of grieving and I know there will be much pain and mourning ahead. But as I sit by the playful, gurgling river, I know the memories that scald now will soothe me later. And when I reach out for my father, he will always be there. Music was the best of him. It is the best of us all.

(c) Eben Harrell

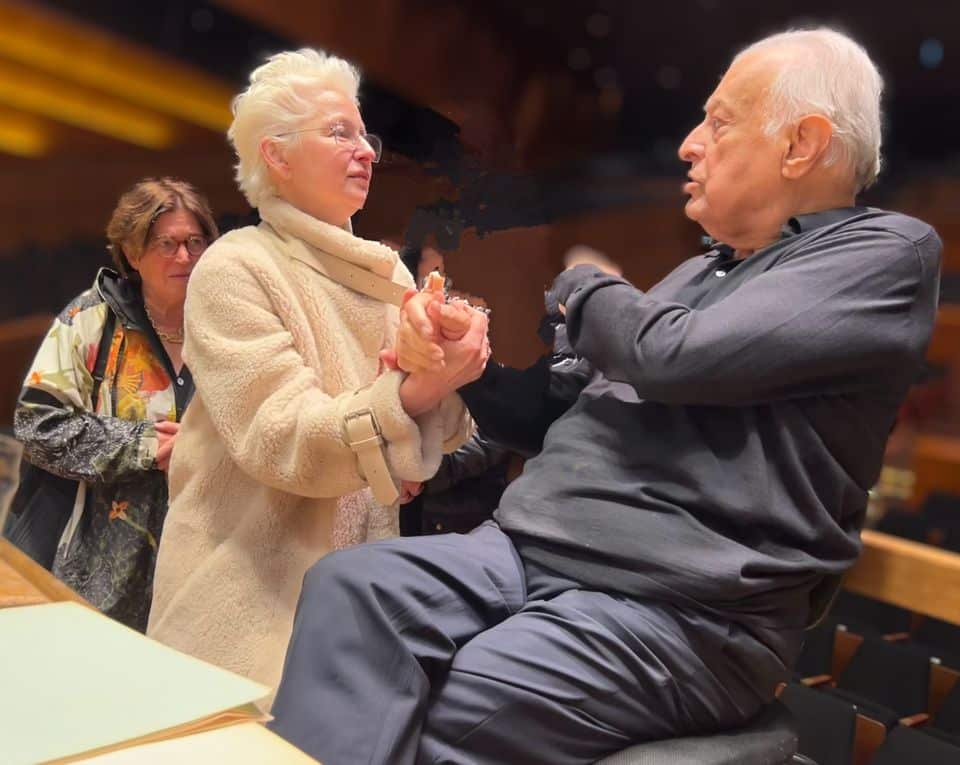

Lynn Harrell playing Bach at the border of South and North Korea, April 27, 2019.

Comments