What’s Beethoven harping on about here?

mainWelcome to the 54th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

String quartet no 10, The Harp, opus 74 (1809)

It is the year of the Emperor Concerto. Beethoven was at the summit of his fame and success. Publishers in three countries were demanding new works. Aside from his deafness and some worries about his brothers and their families, he should have been basking in his achievements and enjoying some of the rewards.

Instead, he lived in squalor. Here’s a visitor’s report from this time:

‘Picture to yourself the extreme of dirt and disorder: pools of water decorating the floor and a rather ancient grand piano on which dust competed for room with sheets of written or printed notes. Under it – I do not exaggerate – an unemptied chamber-pot… Most of the chairs had straw seats and were decorated with clothes and with dishes full of the remains of the previous day’s supper.’

Amid noisome chaos that would drive any sensitive person outside for fresh air and a fire hose, Beethoven created works of taut discipline, not a superfluous note, each part fitting the others like a machine-tooled jigsaw. From time to time he rushed to his brother’s cellar to hide from the unbearable noise of French guns.

The tenth of his string quartets takes its title The Harp for its plucked sections in the opening movement. Its opening is as laidback and relaxed as Beethoven ever gets. He even marks it sotto voce, so quiet it is announced as if under its breath. The second movement, equally slow, was a favourite of Mendelssohn’s for its lilting, smiling melody, as if the composer had not a care in the world. The contrast with his physical situation and the surrounding uncertainty is so extreme as to suggest a possible bipolar condition. The third movement opens with a flagrant allusion to the opening of the fifth sysmphony. The finale has a retrospective feel to it, as if the composer is looking back at his rackety life thus far and preparing himself for the next great leap.

The Melos Quartet, a mainstream German ensemble from the 1960s on, present a textbook performance that leaves the listener plenty of room to fantasise about the composer’s ultimate intentions. If I had never heard the work before, I should probably start here, and maybe return to it as a point of reference, although not for ultimate revelation. You will want more salt and pepper in subsequent hearings.

Remarkably, the first recordings of this concerto were made in the mid-1930s by two Hungarian quartets – the Lener Quartet, which lasted only until 1939, and the Budapest Quartet which continued in different formations until 1967 having settled after much turbulence in the United States. Both of these performances are highly individualistic, the characters of their players emerging with striking difference. The calibre of the Budapest – Joseph Roisman, Sasha and Mischa Schneider, István Ipolyi – is a cut above and the vigour of their playing takes the breath away. A much later best-selling recording for Columbia lacks the original fire. A third Hungarian quartet – Sandor Vegh‘s in 1952 – is perhaps just a little too Magyar, sloping the accents some way off the straight and narrow, albeit in the most agreeable fashion. Wrong as it may be, I do love this reading.

Half a century later, in 2002, the Hungarians rise again with a rivetting Decca recording by the Takacs Quartet – Edward Dusinberre, Károly Schranz, Geraldine Walther, András Fejér – that has just about everything: poise, fantasy, wit and perfectionism. Not quite in the same class (though still of interest) is the Bartok Quartet (2014), playing a little too safe. I have no way of explaining why the Hungarians understand this quartet more roundly and profoundly than anyone else, but the recorded evidence is incontrovertible.

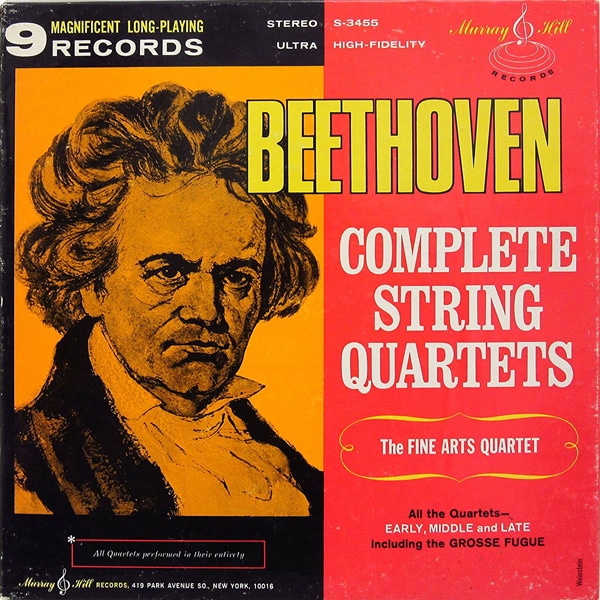

There is also a line of development in American interpretations of this enigmatic work. The Juilliard Quartet led by Robert Mann (1965) has a locker-room athleticism and a certain roughness to the sound. The Fine Arts Quartet (1966) present greater style and sophistication – also greater relaxation: listen closely and you’ll hear how American life has speeded up since then.

The Guarneri Quartet (1970) are masterful, measured, magisterial: one imagines pupils sitting at their feet, knowing that they will never attain this exceptional sheen. And I can never hear the Emerson Quartet (1997) without learning something new – in this instance, the play of light and wit in the theme and variations in the finale. As with the Hungarians, we are witness to an evolving tradition.

There is more contrast to enjoy – the warmth of the Amadeus (1988), for instance, against the clinical coolness of the Alban Berg Quartet (1979), or the studied hush of the Belcea Quartet (2012) compared to the headlong passion of the Cuartetto Casals (2019). And for the most exquisite and timeless eleganceno-one should ignore the Quartetto Italiano at their peak. If pressed, I would choose the Budapest and Takacs as being the most indispensable.

That a single string quartet can accommodate so many different style is itself a testament of its genius. And bear in mind that the Harp is not, by any measure, the most important of Beethoven’s string quartets. When we arrive at the late works the approaches are so varied that there is no telling right from wrong. All we can do is marvel at the diversity.

Comments