How Beethoven dealt with Mozart’s shadow

mainWelcome to the 62nd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Variations in F major on Mozart’s ‘Se vuol ballare’ for Violin and Piano WoO 40

The story goes that Beethoven,aged 17, was brought to Mozart’s home in Vienna and told to play something. He struck up Mozart’s C minor concerto, only to be told to perform something of his own. Mozart was impressed, telling his wife Constanze, ‘watch out for that boy, one day he’ll give the world something to talk about.’

Whether that meeting ever happened in 1787 is a matter of conjecture. Beethoven certainly visited Vienna but Mozart was mostly out of town and there is no reliable corroboration of the anecdote. What is certain is that Beethoven knew Mozart’s music and was confident enough when writing his own not to attempt imitation. By the time he returned to Vienna as a young composer in November 1792, Mozart had been dead less than a year and there was a big gap in the pantheon. Beethoven was talked about as a successor but he understood that, to make his name, he needed to be different from Mozart in significant ways.

Knowing Mozart’s music, however, he could not altogether escape its influence, nor did he want to. At key points in his mature output, he references Mozart, consciously or otherwise. The opening of his Eroica symphony, for instance, is strikingly similar to the introductory phrase of Mozart’s little opera Bastien et Bastienne. Compare them here. And here.

A second affinity can be found in the start of the third movement of Beethoven’s fifth symphony (here) and the first eight notes of Mozart’s 40th symphony (here). There is also a case to be made that Beethoven’s 3rd piano concerto in C minor draws upon Mozart’s in the same key, the one that Beethoven allegedly started to play at Mozart’s home. Did that experience challenge him to go one better in C minor?

These echoes are extremely interesting without being of lasting significance in our appreciation of Beethoven’s originality. Sure, he quoted from Handel’s Messiah in the Missa Solemnis, but that work could not have been written by anyone other than Beethoven. We know that at an open-air performance of Mozart’s C minor concerto Beethoven said to a pupil, ‘Ah, Cramer, we will never be able to do anything like that.’ Somewhere within that remark one can imagine Beethoven thinking, ‘thank goodness we don’t have to do anything like that.’ Beethoven never saw himself as the next Mozart, only as a completely different kind of composer.

He was unstinting in his appreciation of Mozart’s operas and, in his first months in Vienna in 1792-3, he composed four sets of variations, two on themes from Marriage of Figaro and two from the Magic Flute. Only one of these essays made it into his final catalogue but they have always been popular with audiences.

The ‘Se vuol ballare’ theme from Figaro uses the violin initially as a plucked instrument before the piano changes to a plusher sound. Yehudi Menuhin and Wilhelm Kempff, opposites in almost every human aspect, are aptly matched for cut and thrust in the 12 variations on this 1970 recording. One can almost smell the effort each of them was making to stay polite. Elsewhere, in a fairly thin field, I am also drawn to a 2019 set by James Ehnes and Andrew Armstrong, a convincing reflection of a young composer’s respect for a half-resented forbear.

Variations in C major on ‘Là ci darem la mano’ by W. A. Mozart for 2 Oboes and Cor anglais WoO 28

Better known by far is Beethoven’s riff on a Figaro theme delivery boys were whistling in the Vienna streets. The appeal of this piece is so extensive that musicians have often felt free to change the instrumentation. The woodwinds of the Berlin Philharmonic, for instance, deliver a horribly reverential, pedestrian group exercise. Sabine Meyer, her brother and a friend play on two clarinets and a bassethorn, nothing like what Beethoven had in mind but warmer and livelier than the Berliners.

The Frenchman Francois Lelux goes for oboe, clarinet and bassoon, perhaps the most convincing of these renditions. Avoid, at all costs, the London Baroque Ensemble‘s prissy, undernourished take of 1991.

Variations in F major on ‘Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen’ by W. A. Mozart for Violoncello and Piano op. 66

There is a veritable cornucopia of high-powered performances on record. Pablo Casals and Rudolf Serkin at Perpignan in 1951, before the cellist had fully established his summer festival at nearby Prades, give an account of great restraint and solemnity, perhaps still shadowed by the recent war. For painful beauty, it’s hard to beat.

Gregor Piatigorsky is always compelling and, with the Lukas Foss at the piano, memorably challenging as well.

Mstislav Rostropovich has Vasso Devetzi as his pianist on a little-known 1974 recording in which the cellist seems more than usually restrained but unfailingly glorious in tone. For demonstration purposes you would want to play János Starker and Rudolf Buchbinder, both pedagogically inclined. My ultimate choice would be Mischa Maisky and Martha Argerich, utterly uninhibited and full of the mischief that Mozart first invested in this aria.

Variations in E flat major on ‘Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen’ by W. A. Mozart for Violoncello and Piano WoO 46

This aria sounds as if it started as a nursery rhyme and got lost on the way to the bathroom. Taken literally – as Elly Ney and Ludwig Hoelscher play the score – it is insufferably puerile. Given some air by Alfred Cortot and Casals (1927), it’s a different piece altogether, a gentle rejoicing in the pleasures of love and life itself.

You might find Yo Yo Ma a bit big in this, even with Emanuel Ax at the piano, urging restraint. Mischa Maisky and Martha Argerich are inevitably recommendable. But spare a few moments for a 2015 Wigmore Hall recital by Ralph Kirshbaum and Shai Wosner, a performance that brings out the serene informality and semi-privacy of chamber music at its best.

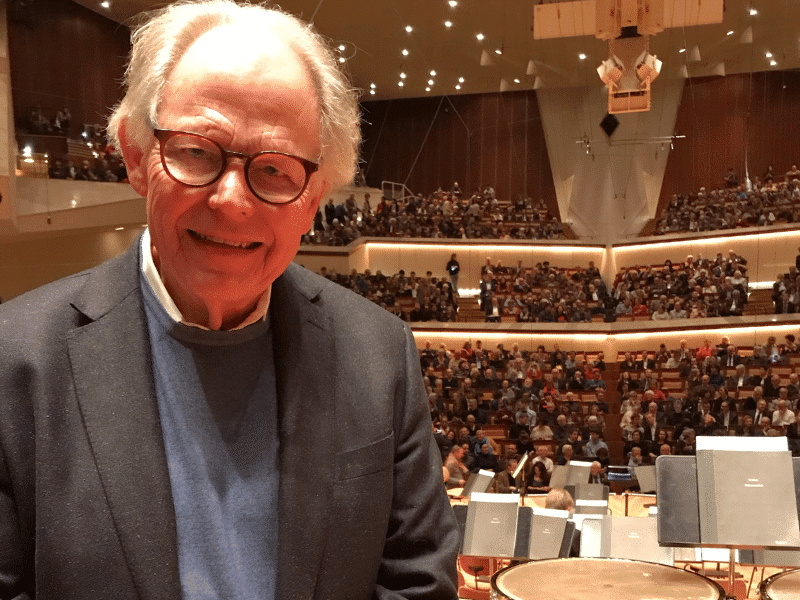

A fantasy illustration from the fanciful meeting

Comments