When Beethoven’s Fifth split down the middle

mainWelcome to the 37th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Beethoven: 5th symphony (part 3)

With the coming of stereo at the end of the 1950s, performance of the Beethoven symphonies split down the middle – traditional, large orchestras to one side, small ensembles and period instruments to the other.

It took a while for the period pack to reach Beethoven. They spent the 60s in Haydn and the 70s in Mozart before anyone dared to address the big B. I think Monica Huggett and her Hanover Band – the LP cover said ‘on original instruments’ might have been first. Recorded at All Saints Church in Tooting, London, in May 1983, it’s an unusually clean performance for its time with few cracks in the valveless horns and good ensemble throughout. Huggett, primarily a violinist, was also concertmaster for Ton Koopman at the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra. The adventurous recording label was Nimbus.

Four years later, the much more famous Christopher Hogwood and his Academy of Ancient Music released Beethoven’s fifth on Decca, with less of a bang than a whimper. The tempi are unconvincing and the string quality sandpapery. Neither the original pitch nor Hogwood’s direction sets the imagination afire and some passages in the finale practically dissemble before our ears.

Roger Norrington with the London Classical Players in 1988 is far more subtle, thoughtful and introspective. This might be the quietest Beethoven Fifth ever made and the speeds are slow slow at times that the texture becomes transparent and one glimpses effects never heard before – like land exposed by a receding sea. It lacks the sweep of a Walter or a Szell, but the experience is nonetheless rewarding.

Nothing subtle about Sir John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique in 1994. This Panzer approach to Beethoven, with all guns blazing, is unquestionably exciting so long as you’re not about to get rolled over by the advancing tanks. Where the rush comes unstuck is in the second movement, which ought to arouse feelings of affection and sounds more like rape. Several on our panel pick Gardiner as their first choice. The playing is first-class.

Frans Brüggen with the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century (1992) offers a measured counterpoint, a pastoral narrative. Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1990), with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, is so unfussy as to be almost prosaic, although the symphony wakes up in due course. For a sugar-free, vegan approach, try Jos van Immerseel and Anima Eterna Brugge (2008).

Meanwhile, mainstream conductors were stealing the early-music movement’s clothes. Simon Rattle with the Vienna Philharmonic and, more consistently David Zinman with the Zurich Tonhalle orchestra were preaching period practice and tempi for performance on modern instruments. Zinman’s cycle is the most impressive of its time and his account of the fifth symphony is darkly memorable.

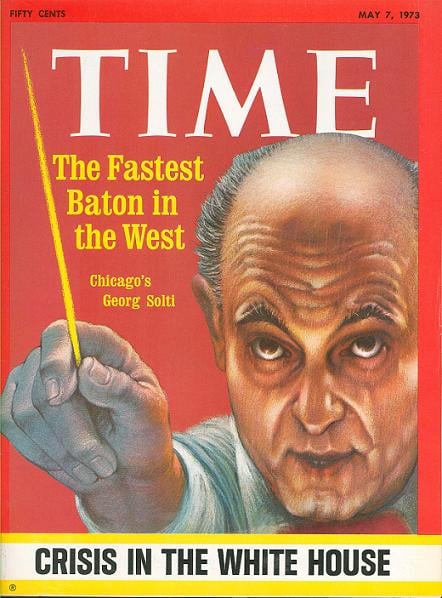

Among the unreconstructed big-band practitioners, Sir Georg Solti and the Chicago Symphony stand out for sheer vigour and vitality. Chicago, in Solti’s heyday, was the loudest orchestra in America and the conductor’s impetus brooked no resistance. Not for Solti the arguments of period authenticity. ‘Why should I prefer replica 19th century instruments that were made the week before last to the finest valve horns of the 19th century?’ he once demanded. His symbiosis with Chicago was founded on mutual underdog perceptions. Chicago resented its secondary cultural status to New York and Solti was infuriated by record critics who referred to him as ‘second only to Karajan’.

In the fifth symphony, recorded in 1975, these sentiments coalesced into a performance of massive power and beauty, a paradigm of one of the great conductor-orchestra partnerships. Every single one of the principal players is world class.

Among later interpreters, Mariss Jansons with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, on Japan tour in 2012 stands out for clarity and cohesion. Jansons spent hours adjusting the placement of seats in the orchestra, a millimetre to the right or left, to achieve the exact blend of sound that he wanted to hear. The playing standard is the highest in Germany outside Berlin, and is raised a notch or two on tour as the orchestra competes in Suntory Hall for yen supremacy – a match-winning performance.

So – final pairings for the Fifth Symphony, in order of opposites:

Erich and Carlos Kleiber, in that order

Nikisch and Richard Strauss

Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer

Furtwängler and Karajan – both 1954

Huggett and Norrington

Solti and Jansons.

If you’re the type of person who never drives without a safety-belt or leaves the house without pushing the door twice, you may find kindred souls in the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra’s conductor-free performance of October 2012. On the other hand, you might just loosen a couple of buttons on your shirt and decide to live a little.

Comments