Is there such a thing as a Beethoven violinist?

mainWelcome to the 33rd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Beethoven violin sonatas 1-3, opus 12

We all know what a Beethoven pianist is. It’s someone who addresses the monumental challenge of the 32 sonatas, plus the five concertos and other occasional pieces. The piano was Beethoven’s instrument, his most direct form of communication. The pianist is his surrogate.

But the violinist? Aside from the violin concerto, which is probably the most important work of its kind, there is no Beethoven imprimatur for the instrument. True, he wrote ten sonatas for violin and piano, which is more than most composers, but they belong on the whole to an early period when he is still finding his voice. The first set of three, opus 12, which I’ll discuss in a moment, date from the 1790s ad are dedicated to Antonio Salieri, the politically manipulative composer who acted as a fixer in musical Vienna and may – mostly likely may not – have murdered Mozart. Either way it was important for Beethoven to get on the right side of him with a set of sonatas that sound as if they could have been written by Mozart.

The other influence is the violinist Rodolphe Kreutzer (1766-1831) whom Beethoven had just met, and who would go on to inspire his most celebrated sonata for violin and piano. Kreutzer was a busy teacher who favoured flashy fingerings. Beethoven was encouraged to make his sonatas hard to play The first review, in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, condemned him for ‘contrariness and artificiality’. The audience, however, responded warmly.

So what is a violinist to make of Beethoven’s first approach to the instrument?

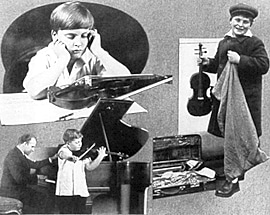

Yehudi Menuhin, aged 13, in a 1929 recording with his sister Hephzibah, displays a syrupy tone in the first sonata that mimics the crowd-pleasing effects perfected by the older generation of Ysaye and Enesco. The tone grates on the ear as the initial charm wears off. A 1955 Abbey Road recording by Menuhin with his brother-in-law Louis Kentner is quite alarmingly tentative, questioning, two characters in search of the real Yehudi Menuhin. By 1970, when Menuhin plays with Wilhelm Kempff, he is lost, a voice in the wilderness seeking his redeemer. These sonatas bring out, better perhaps than any other music, the tragedy of Menuhin’s irresoluble self-doubt, rooted in a tormented childhood.

Joseph Szigeti, partnered by Claudio Arrau in 1944, is something else altogether. Slick and quick, they have no concern at all for Beethoven style and seem rather keen to get home for news of theD-Day landings. Arrau is an equal-rights accompanist: no violinist will ever get ahead of his piano.

Who remembers Henri Temianka? In 1946, the Scottish born, Polish-Jewish violinist played all 12 Beethoven violin sonatas with pianist Leonard Shure at the Library of Congress in Washington DC. The pianist dominates the early exchanges and the sound is borderline acceptable/execrable, but Temianka is an assured performer and these concerts were the springboard for launching an international chamber music career that last almost half a century.

Jascha Heifetz outshouted his pianists; this 1947 account with Emmanuel Bay diplays him at his worst: flawless, cold and metronimic. Not a Beethoven violinist by any imaginative stretch, just the best violinist that ever lived.

With Arthur Grumiaux and Clara Haskil we reach a plateau of satisfaction, especially in the second sonata. A Belgian violinist who was almost as adept as a pianist, Grumiaux has a fine way of story-telling, amply matched by Haskil’s Mozartian twinkle at the piano. This reading must appear on any shortlist of recommendations.

Whispering Christian Ferras (1959) and authoritatian Wolfgang Schneiderhan (1961) subdue their tentative accompanists, as does Zino Francescatti (1965).

Itzhak Perlman’s set with Vladimir Ashkenazy (1977) was the go-to interpretation of its day. Perlman was Heifetz with central heating, and much else besides. He engaged full-on with an audience, and Ashkenazy was anything but reticent. This was late 20th-century power playing and it may never be bettered. Whether it speaks to a future generation is another matter. Both musicians have so complete a solution to the Beethoven problem, they leave listeners little room for fantasy.

The Soviets presented us with a choice of David Oistrakh or Leonid Kogan, the latter accompanied in Leningrad (1964) by his brother-in-law Emil Gilels. Grim sound, but sensational Beethoven. Oistrakh has Richter at the piano. The two violinists are natural antipodes. No critic should be forced to make such a choice.

Gidon Kremer and Martha Argerich (1984) are gin and tonic, irresistible at the right time of day. Anne Sophie Mutter is next-gen Perlman (1998) but Lambert Orkis is no Ashkenazy.

Among the period-intrument pairings, Elizabeth Wallfisch with David Breitman (2012) finds an authentic-sounding domesticity, a replica of the kind of presentations that Beethoven gave in the gilded drawing rooms of his ghastly Viennese patrons, who probably chatted all the way through. Viktoria Mullova (violin, 2010) with Kristian Bezuidenhout (fortepiano) are a lot showier, less deferential to period discourtesies.

Among 21st century practitioners, the standouts are a prizewinning performance by Yukiko Uno (violin) and Takashi Sato (piano) at the 2019 Queen Elisabeth contest in Brussels, and the elegant Isabelle Van Keulen with Hanness Minnaar in 2014. For intuitive communication, listen to Pamela Frank with her father Claude Frank in a non-commercial recording from 2011.

Final reckoning? Grumiaux, Oistrakh, Kogan, Kremer, Wallfisch, Uno, Frank.

Which of them is a Beethoven violinist? No such thing, I’m afraid.

Bonus track: Variations on national airs for flute or violin/piano, opus 105 and 107

Beethoven’s final commission from the Scottish publisher George Thomson was for a chamber setting of folk tunes from the Austrian Empire and the British Isles. He gave the publisher two options: the works can be played by either on flute or violin, with piano accompaniment. The French flute virtuoso Patrick Gallois has a lovely set with pianist Cecile Licad, while Daniel Hope is perhaps the pick of the violinists on record, with pianist Sebastian Knauer. Olli Mustonen, a Finnish pianist plays the set without a partner.

There’s no accounting for Finns.

Comments