Beethoven takes two steps back, one forward

mainWelcome to the 39th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Piano sonatas 9 and 10, opus 14, no 11 opus 22 (1798-1800)

Regression is extraordinarily rare in Beethoven’s output. He seems to take a giant stride forward with each work and never to look back. So it’s almost a relief to find that, coming towards the end of his early period, he wrote a set of piano sonatas that were intended for home use, easy enough for a half-trained amateur to knock off on the family upright after lunch. The opus 14 sonatas are inscribed to Baroness Josephine von Braun, wife of the head of what would become the Vienna Opera, and they are so disarmingly simple to play you wonder if great minds of the instrument might have found in them some mysterious hidden depths.

Maurizio Pollini (2013) one of the most serious contemplators of the Beethoven sonatas, fails in the ninth sonata. His boundless technique, applied to a folktune opening (is it My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean?) reminds me of a brain-surgeon’s scalpel being used to crack open a peanut. Andras Schiff (2006) is a little more playful, but the effort to amuse becomes tiresome as the work progresses. Murray Perahia (2008) tries some blood and thunder, to the same limited effect. Richard Goode (1993) is very good indeed without fully engaging the listener’s heart and mind. Artur Schnabel (1932) plays it like a walk in the park.

Before I sound too dismissive, the Canadian pianist Angela Hewitt (whose recording is not yet on Idagio) points out in a sleeve note that ‘small hands will have difficulty with bars 17–20 and breaking the chords is musically not very satisfying…. The sforzando alternations between G natural and G sharp in bars 46–49 must be brought out while the inner part remains piano, and the bass a determined forte. The notes aren’t complicated, but their characterization is.’ Hewitt is surprised to find ‘how close the writing is to that for a string quartet’. Myself, I don’t hear that.

Matters don’t much improve with its companion piece, the tenth sonata. The opening looks back determinedly to the sonatas of Joseph Haydn, where the sun is always shining and there’s a lovely young maiden bringing a two-foot glass of beer to a thirsty composer (I may exaggerate, but you get the idea). Given the lack of complextity, I thought I’d listen to some lesser-known interpreters – Saleem Abboud Ashkar, for instance, a Palestinian-Israeli Christian from Nazareth who recorded four Beethoven sonatas for Deccca in 2017. Without knowing much about him, I was reminded of Daniel Barenboim who, it turns out, has been his mentor. For sheer freshness, I preferred Saleem to Barenboim’s 1984 recording, made at about the same age.

Not far down the road, there’s Einav Yarden of Tel Aviv, a student of Leon Fleisher’s at Baltimore, now teaching in Germany. Lovely, warm tone, not much by way of humour in the nursery-rhyme middle movement. The Lebanese Abdel Rahman El Bacha has recorded all 32 sonatas on the Mirare label; he’s very fast in this one, ideal for your morning workout.

Daniel-Ben Pienaar, a South African now teaching at London’s Royal Academy of Music, has levity in the opening movement, growing heavier as the work progresses. Konstantin Lifschitz adds wit to the picture. A Russian-Jewish pianist living in Switzerland, his 2019 recording in Hong Kong has an abundance of character, almost too much for this flimsy piece. But I prefer his reading to such heavyweights as Igor Levit who seem to be playing for posterity. Lifschitz deserves more applause than he gets at the end of this recital.

Prepare for a revelation. Trudelies Leonhardt, sister of the Dutch early-music master gives an absolutely stunning Haydneqsque reading of this harmless sonata on as deep-voiced fortepiano. I would also urge you to enter the richly coloured world of the Canadian pianistLouis Lortie who, in recording the 32 sonatas, leaves no phrase unplumbed for inner meaning.

When all’s said and done, though, the only pianist who consistently challenges and surprises us in these determinedly unchallenging and unsurprising sonatas is the unfathomable and insuperable Russian pianist Sviatoslav Richter who, at tempi and dynamics that are entirely his own, recreates whatever music he touches in a manner that is unteachable and does not bear imitation. This Decca recording from 1963 takes us places that Beethoven never imagined.

Beethoven gets back on track with his 11th sonata, the one he was most proud of among his early efforts. The opening phrase delares it to be a big statement and, while the sonata is not known to the public as a major milestone, many pianists look upon it as such. In the middle of the 20th century it was said to be practically unplayed, returning to the British concert hall through the advocacy of John Lill and Bernard Roberts, neither of whom are found on Idagio. My starting point is Louis Lortie (1998) with a youthful freshness that conceals structural assurance. His hushed storytelling in the slow movement is masterly, suggesting deep tensions beneath an apparently untroubled surface. This is music making at the very highest level – a realm occupied on record by the likes of Brendel, Ashkenazy, Kempff, Gulda and Arrau.

You need to listen to Maria Grinburg, in terrible Soviet studio sound, just to hear how Beethoven can sound when an artist gives no thought to safety or career, just to preserving an early-Russian style that, she must have known, would not survive contact with the material world. Richter is als wonderful and Lifschitz needs to be heard. When all is said and played, though, in this sonata I will always return to Emil Gilels. He says it all. Just listen.

*

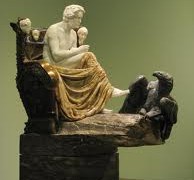

For your weekend reading, I would like to direct you to the website of the Beethoven House in Bonn, where Jessica Duchen offers a guided tour in how Beethoven’s image changed down the years – from handsome youth to gruesome monster. Jessica writes: I’ve seen descriptions of him as “physically ugly” time and again. But those Young Beethoven images – why? Physically ugly? No: he is strong, characterful and full of charisma. Besides, the attraction of a male musical star has never depended upon classic good looks (I’ve not noticed Hollywood-style matinée idols among the Beatles or the Rolling Stones or any recent pop singers, for instance…). Just because he was short and dark, that is no reason that Josephine or Julie or any other female would have failed to be magnetised by him.

Read on here.

Comments