The Siberian State Symphony Orchestra has cancelled its 2020 US tour after being denied visas.

CAMI Music chief Jean-Jacques Cesbron enlisted US Senator Dianne Feinstein in a bid to change the verdict, but to no avail.

No reason was given.

It’s cold war out there.

The London-based Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment has decided to travel by train, not plane, on this month’s visits to Poland and Hungary.

The switch will increase the journey time from two and a half to 24 hours, but the CO2e saving will be 15,000 metric tonnes.

The period-instrument band aims to be a brand-leader in environmental awareness.

The Spanish conductor Gustavo Gimeno has renewed to 2025 with the Luxembourg Philharmonic Orchestra.

Gimeno, 44, recently signed on as chief with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, giving him major North American exposure.

What has little banking Luxembourg done to keep him?

The clue’s in the lux.

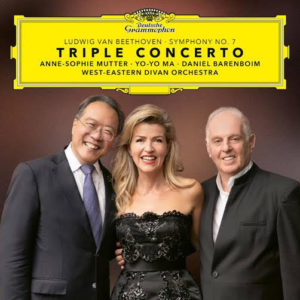

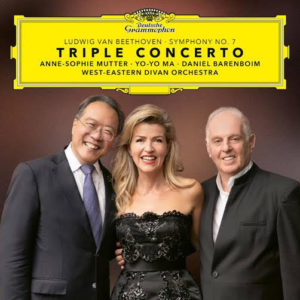

The recorded history of Beethoven’s triple concerto is littered with disasters, none more embarrassing than Herbert von Karajan’s conduct when he was confronted by the three Soviet stars, Richter, Oistrakh and Rostropovich.

Richter said: ‘It’s a dreadful recording and I disown it utterly…’

Now DG have unveiled their team for the Beethoven centenary.

What could possibly go wrong?

Ivo Van Hove’s new Broadway production of the Leonard Bernstein musical has been marred by nightly demonstrations against one of its dancers, the Bronx-born Amar Ramasar.

Ramasar, 38, had been fired in September 2018, then reinstated by NY City Ballet, after he was sent nude photos of Alexandra Waterbury, a fellow-dancer, without her consent. Waterbury implicated her ex-boyfriend, Chase Finlay, and another NYCB dancer, Zachary Catazaro, in the offensive distribution. Finlay resigned from the company. Ramasar was taken back after intervention by his union, the American Guild of Musical Artists.

We have been asked to clarify that Amar Ramasar didn’t circulate images of Alexandra Waterbury, and Alexandra’s lawsuit does not allege that he did. He received her images from Chase Finlay and did not share them further, and the lawsuit does not allege that he did. Amar replied with an image of his own girlfriend, Alexa Maxwell, who issued a statement last week, that Amar has regained her trust and they are putting this mistake behind them

You can read the lawsuit here.

The producers of West Side Story issued this reason yesterday for retaining him:

The West Side Story Company stands, as it always has stood, with Amar Ramasar. While we support the right of assembly enjoyed by the protestors, the alleged incident took place in a different workplace — the New York City Ballet — which has no affiliation of any kind with West Side Story, and the dispute in question has been both fully adjudicated and definitively concluded according to the specific rules of that workplace, as mandated by the union that represents the parties involved in that incident. Mr. Ramasar is a principal dancer in good standing at the New York City Ballet. He is also a member in good standing of both AGMA (representing the company of NYCB) and Actors’ Equity Association (representing the company of West Side Story).

There is zero consideration being given to his potentially being terminated from this workplace, as there has been no transgression of any kind, ever, in this workplace. The West Side Story Company does not as a practice terminate employees without cause. There is no cause here. The West Side Story Company’s relationship to Mr. Ramasar is completely private to that company and exists solely between Mr. Ramasar and his fellow company members. He is a valued colleague who was hired to play a principal role in this production, which he is doing brilliantly, and which he will continue to do for the entire unabated length of his agreement.”

Waterbury’s supporters on change.org retorted:

The statement released by West Side Story today demonstrates that the production cares more about money and talent than the safety of its performers. Amar Ramasar’s behavior at City Ballet was vile — yet West Side Story chose to hire him anyway.

Just because the production is not legally obligated to fire him doesn’t eliminate their moral obligation to keep abusers off the stage. Ramasar shared explicit photos of fellow ballerinas without their consent. His behavior was disgusting, damaging and unlawful.

Despite the parish paper’s invocation of a ‘new era’ at the Met, the novelty value is confined to a clutch of fashionable directors and a showing of Heggie’s Dead Man Walking, ordered to please Diva Joyce. There are just five new productions.

What caught our eye more than the glitz is the number of conductor debuts, some of them long overdue.

Here’s a list:

Lorenzo Viotti in Carmen

Hartmut Haenchen in Tristan

Speranza Scapucci in Traviata

Michail Jurowski in The Fiery Angel

Nimrod David Pfeffer in Bohème

Giacomo Sagripanti in Barber

Jakub Hruša in Rusalka

Kensho Watanabe in Dead Man Walking

At least three of these names are making serious waves in the world. And it’s good to see Italians back in the reckoning.

These appointments might be Yannick’s major contribution to the ‘new era’.

The Manhattan parish paper has picked up our exclusive story on Anthea Kreston teaching violin in China during the coronavirus epidemic.

The paper does not credit Slipped Disc.

It’s too parochial.

Read the NYT interview here.

Latest review from Birmingham in the exclusive Slippedisc/CBSO100 season coverage:

CBSO at Symphony Hall ★★★

The gear change required between the opening andante and subsequent allegro sections in the first movement of Schubert’s Symphony No. 9 is notoriously difficult to navigate. Start with the famous solo horn theme too slowly and portentously and when it returns triumphantly in the coda it’ll sound like a speeded-up record. Juanjo Mena avoided this pitfall; the tempi matched seamlessly and there was no need for an old-school ritardando. There was a price to pay though as Mena’s relentless briskness gave it a Rossini-like lightness and banality. Elspeth Dutch’s horn call was perfect for Mena’s approach but never suggested the promise of romance and mystery that left Schumann awe-struck. As we raced onward the symphony was gradually stripped of its majesty with only small pockets of beauty as compensation. Mena used a large body of strings but, in not doubling the wind section, left much of their music inaudible.

These deficiencies were highlighted by a wonderfully attentive, scrupulously observed and moving performance of Berg’s violin concerto. Ilya Gringolts, a late replacement for the indisposed Leila Josefowicz, was always gritty enough for the concerto’s occasional acerbities, there was a spirited tussle with the snarling trombones as the soloist’s nemesis, but also produced playing of ravishing beauty – the final Bachian chorale was balm from heaven. Mena ensured that Berg’s large orchestral forces were handled deftly, always allowing crucial details their full weight – such as the uncannily life-like impersonation of a small church organ by the clarinets of Oliver Janes and Joanna Patton.

Norman Stinchcombe

We are disturbed to learn that San Diego Opera has co-commissioned a new work with the US Army which ‘captures the spirit of the U.S. Military and explores themes of family, service, and sacrifice.’

The task of an Army is to make war. The job of an opera house is to make opera.

No useful purpose is served by blurring those roles except, perhaps, in San Diego’s case, to please the Texas garrison. This feels all wrong.

Press release below:

San Diego Opera’s 2019-2020 season comes to a close with Zach Redler’s opera about military spirit with The Falling and the Rising. The Falling and the Rising opens May 8, 2020 at 7:30 PM at the Balboa Theatre as part of the dētour Series. Additional performances are May 9 at 7:30 PM and May 10 at 2 PM.

The Falling and the Rising is a co-commission between San Diego Opera, the US Army Field Band and Soldier’s Chorus, Seattle Opera, Arizona Opera, Opera Memphis, TCU, and Seagle Music Colony. The Falling and the Rising centers around an unnamed female Soldier who is severely wounded by a roadside IED. Placed in an induced coma to help minimize the extensive trauma to her brain, the soldier must now make a journey towards both healing and home. With a libretto taken from dozens of interviews with active duty soldiers and veterans at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, The Old Guard at Fort Myer, and Fort Meade, Maryland, The Falling and the Rising tells a story of family, service, and sacrifice inside a period of great uncertainty. The opera stars Sergeant First Class Teresa Alzadon (soprano) as the Soldier. She is joined by mezzo-soprano Gabrielle Florez as Doctor 1, baritone Babatunde Akinboboye as Doctor 3, and bass Walter DuMelle as Doctor 4. Casting for Doctor 2 will be announced shortly. Alan Hicks, who directed the season opener Aida, returns to stage the action. Bruce Stasyna, who will have last conducted The Barber of Seville by the time the opera opens, returns to lead these performances. The set and lighting designer is Chris Rynne, who last lit the season opener Aida. The video designer is Caroline Andrew. These are the first San Diego performances of The Falling and the Rising. The opera received its world premiere in 2018 at Texas Christian University. The Falling and the Rising will be performed in English with English text above the stage.

Welcome to the 32nd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Beethoven’s ’10th’ symphony

Musicians and computer technicians are presently racing against the clock to produce a completion of Beethoven’s tenth symphony, using artificial intelligence tools. ‘Robots pitch in to finish Beethoven’s Tenth,’ ran the headline in the Times’s foreign pages and that’s about all we can report about it until the results are performed at an orchestral premiere in Bonn on April 28.

Before you get too excited, let’s examine the backstory, and sample the existing recordings of this contentious, possibly spurious work.

The first twitchings of a tenth symphony stirred in the mid-1980s when a British musicologist, Barry Cooper, produced 250 bars of sketches supposedly written by Beethoven in his final weeks. He offered it early in 1827 Beethoven to the Philharmonic Society in London and the sketches that Dr Cooper worked on were approximately as far as he got before death intervened, on March 27 that year.

Cooper, a lecturer at the University of Aberdeen, collated the sketches into a 15-minute orchestral movement with three subsections – Andante – Allegro – Andante. He thought there might also exist some ideas for a scherzo second movement, but these were not developed enough for realisation. Amid some musicological scepticism from jealous colleagues, Cooper produced a score that was recorded by two different orchestras and conductors, the second of which was accompanied by a lecture from Cooper explaining what he had done.

You can listen to the lecture here.

Cooper’s movement was premiered in London in October 1988 by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by the former Vienna Philharmonic concertmaster Walter Weller, under the auspices of the Philharmonic Society. Learned opinion split down the middle. One newspaper critic, who wrote that the ‘music sounded half formed’, was the composer Anthony Payne who went on himself to make a completion of Edward Elgar’s third symphony. Payne did, however, recognise that there were ‘fresh and fascinating things’ to be heard in the Cooper score. Within a week, a second performance was given by the American Symphony Orchestra and Jose Serebrier at Carnegie Hall. After that, interest faded and there have been few revivals – until the present Beethoven anniversary year when the work is being dusted off again for public contemplation.

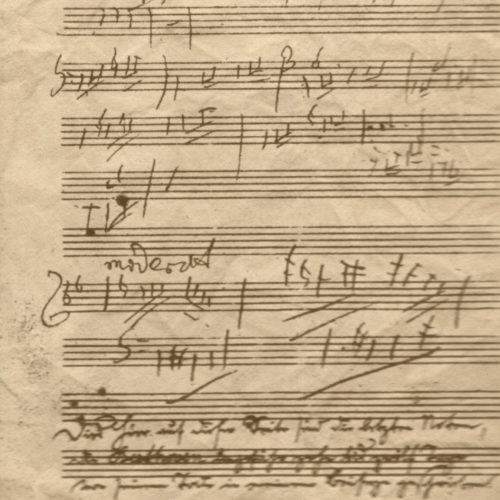

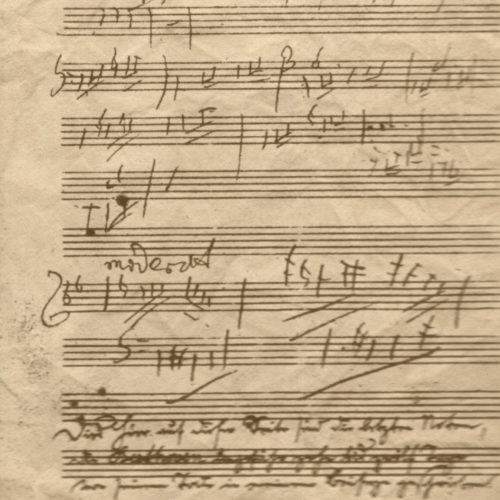

Once the musigologists stopped squabbling it emerged that a violinist called Karl Holtz, who worked as one of Beethoven’s copyists, left an account in which he reported hearing the composer play through some of his material for the tenth symphony at the piano. There is also an archived sheet of music (above) on which Beethoven’s close friend Anton Schindler wrote: ‘These notes are the last ones Beethoven wrote approximately ten to twelve days before his death. He wrote them in my presence.’ That amounts to fairly compelling proof that Beethoven had another symphony in mind as he died, and that these materials were part of it.

So, is it the symphony as it stands worth hearing, and does it advance our understanding of the greatest mind ever to be applied to music?

There is no simple answer to these questions.

Two recordings exist. One is conducted by Weller with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra on Idagio (listen here). The other was rushed out by the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by the blustery Wyn Morris, once referred to as ‘the Welsh Furtwängler’. His performance, archived on Youtube, starts out in a more exciting and emphatic fashion, but loses whatever thread there is in the score and threatens at two or three points to unravel altogether. Weller, in Birmingham, is measured, coherent and sometimes convincing.

The tentative nature of the opening takes some getting used to. Beethoven, so assured in his symphonic statement, appears to be feeling and fidgeting around for something new to say. He falls back on familiar phrases, from the ninth and sixth symphonies, and in the middle section on big-gun bluster from the third and fifth. For the first time since the second symphony, he’s taking us back rather than forward. Was the tenth symphony to be a kind of summation of his symphonic life? We can but speculate. The more you listen to Weller and the CBSO, the more the material seems to be pre-used. At 8:45, it’s the finale of the Ninth, around the 14-minute mark, it’s all Pastoral Symphony.

You have to listen in between the fumblings for a big new theme to hear – at 08:30 for instance and again at 11:10 – that Beethoven is reaching into some deep, dark silence for a sound world he cannot access. And every now and then he draws on the new language of the last string quartets to startle us with hints of atonality. Weller, who had his own string quartet, is acutely attuned to these late parallels. He may have been too subtle and thoughtful an interpreter to achieve popular appeal, but his career around the UK – especially in Scotland, where he was commemorated as principal conductor with his picture on a £50 banknote – did not go unappreciated. It may be that this recording is Weller’s greatest contribution to musical history. I urge people to listen to it at least three times to find their own meanings. The special quality of the fragments of the tenth symphony is to encourage you to build your own Beethoven.

Walter Weller died in June 2015, at the age of 75.

Time for a rethink.