When Pierre Boulez stopped speaking to me

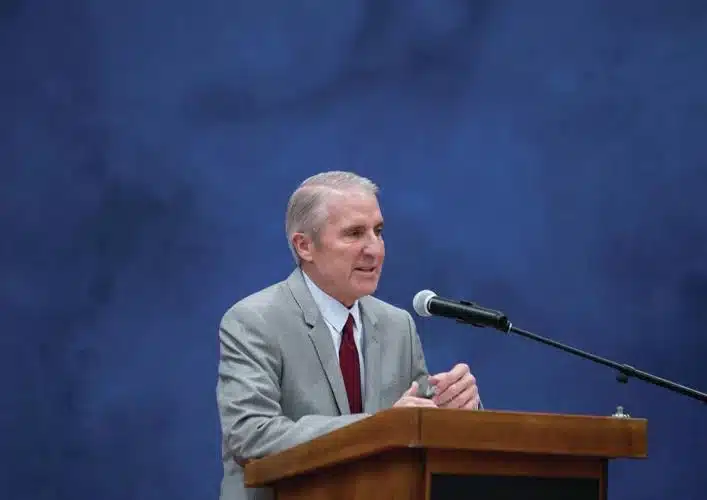

mainIt was George Crumb’s 90th birthday yesterday. Twenty years ago, I wrote a column on his 70th, pointing out that George was possibly the most undervalued living composer and contrasting the modesty of his birthday with the fireworks the music biz was putting on for the 75th of Pierre Boulez.

This is part of what I wrote.

HERE is a wad of ammunition for those who maintain that musical reputations are manipulated by a metropolitan clique of critics, broadcasters and publishers.

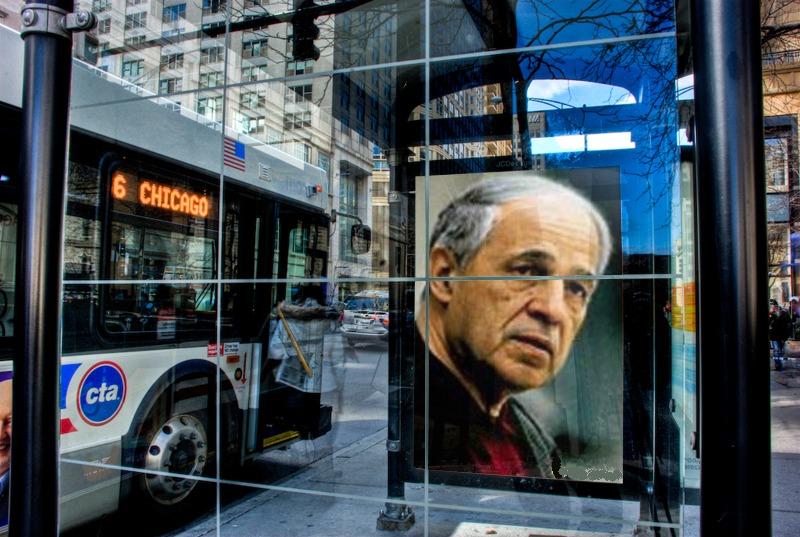

Next month, Pierre Boulez will preside over celebrations of his 75th birthday. The bash begins with an LSO series at the Barbican, followed by an extended tribute at the Festival Hall, every note reverentially aired by the BBC. A gush of records will hit the stores. Interviews will appear in most serious dailies. Until winter’s end, it will be hard to avoid the sight and sound of the amiable French ringleader of post-war avant-gardism. It seems only yesterday that we went through a similar carnival for his 70th.

Last weekend, the American composer George Crumb flew in to play percussion at a 70th-birthday concert in the Wigmore Hall. The gig was put on by a guitar magazine and attended by cognoscenti. No broadcast, not a word in the press – this was as private a party as an MI5 reunion.

The next day I got a call from an orchestra PR saying that my meeting with Boulez in Paris the following week had been cancelled. When I asked why, she said he had taken against being compared to an American composer, especially one as obscure as Monsieur Crumb.

Dis-donc!

Well, maybe it was the next two pars that made him see red.

Without stretching the contrast, Boulez is a relic of an empirically discredited movement. He has not composed a work of substance for 18 years. His pseudo-scientific theories of musical progress are laughed off by today’s composers. Not one of his works is standard repertoire. Boulez is starting to resemble Arthur Scargill and Egon Krenz, true believers whose creed collapsed.

Crumb, on the other hand, is one of the few composers to change the perception and function of new music in the last third of the 20th century. His electronic string quartet, Black Angels, was an ear-opener to America’s Vietnam generation, suggesting that Haydn’s art form could grapple with post-nuclear conflict. Hearing Angels inspired the formation of Kronos and other front-line ensembles; it has been recorded four times and performed, I suspect, more than any modern string quartet.

Whatever (which is English for quand-meme)…. at 75 and still vituperative about any composer who did not follow his route, Boulez might have been expected to be able to take a little rough with the supersmooth. Mais, non. With skin as thin as a newborn’s cranium, he banished me from his presence for a few years, after which I may have lost interest in renewing our acquaintance. Tant-pis. I don’t think we ever met again.

Thanks to Abbie Conant for reminding me of the Crumb column.

Comments