104 missing bars of Gershwin

mainFrom the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra:

There are two versions of An American in Paris on this release: the new critical edition of this iconic work, and an unabridged version which includes four passages totaling 104 that Gershwin eventually crossed out. Neither has ever been recorded. The CSO received special permission from the Gershwin estate to record the unabridged edition.

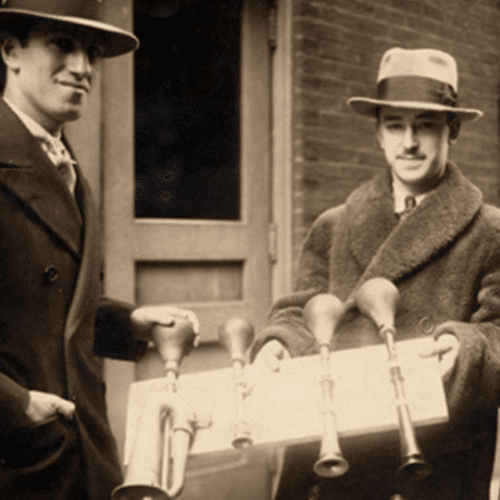

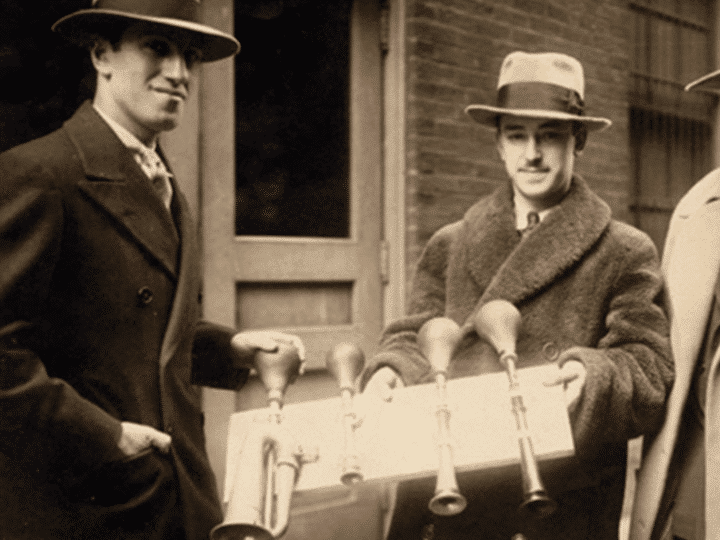

Another notable difference in this new critical edition lies in the taxi horn pitches. The Ira and Leonore Gershwin Archive uncovered a photo of Gershwin in Cincinnati from March of 1929 with CSO percussionist James Rosenberg. They are holding the four taxi horns Gershwin brought back from Paris.

The recording, titled Transatlantic, is out in a fortnight.

Comments