The earliest version of Mahler 10 is brought back to life

mainThe Hong Kong Philharmonic have announced a December performance of ‘Mahler Symphony no. 10: Adagio and Purgatorio (first performance since 1924 of Willem Mengelberg’s performing version)’.

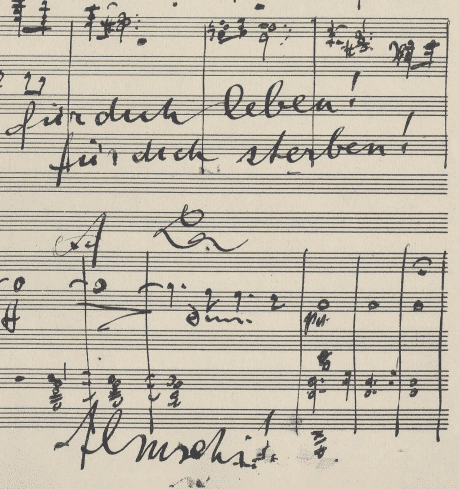

Mengelberg had staged the first complete Mahler cycle in Amsterdam in 1920. He prepared the two near-complete movements of the Tenth but his score was discarded in favour of one by Ernst Krenek, a young German composer who was married at the time to Mahler’s daughter.

Hearing it will be a curiosity.

The conductor is fellow-Dutchman, Jaap Van Zweden.

Comments