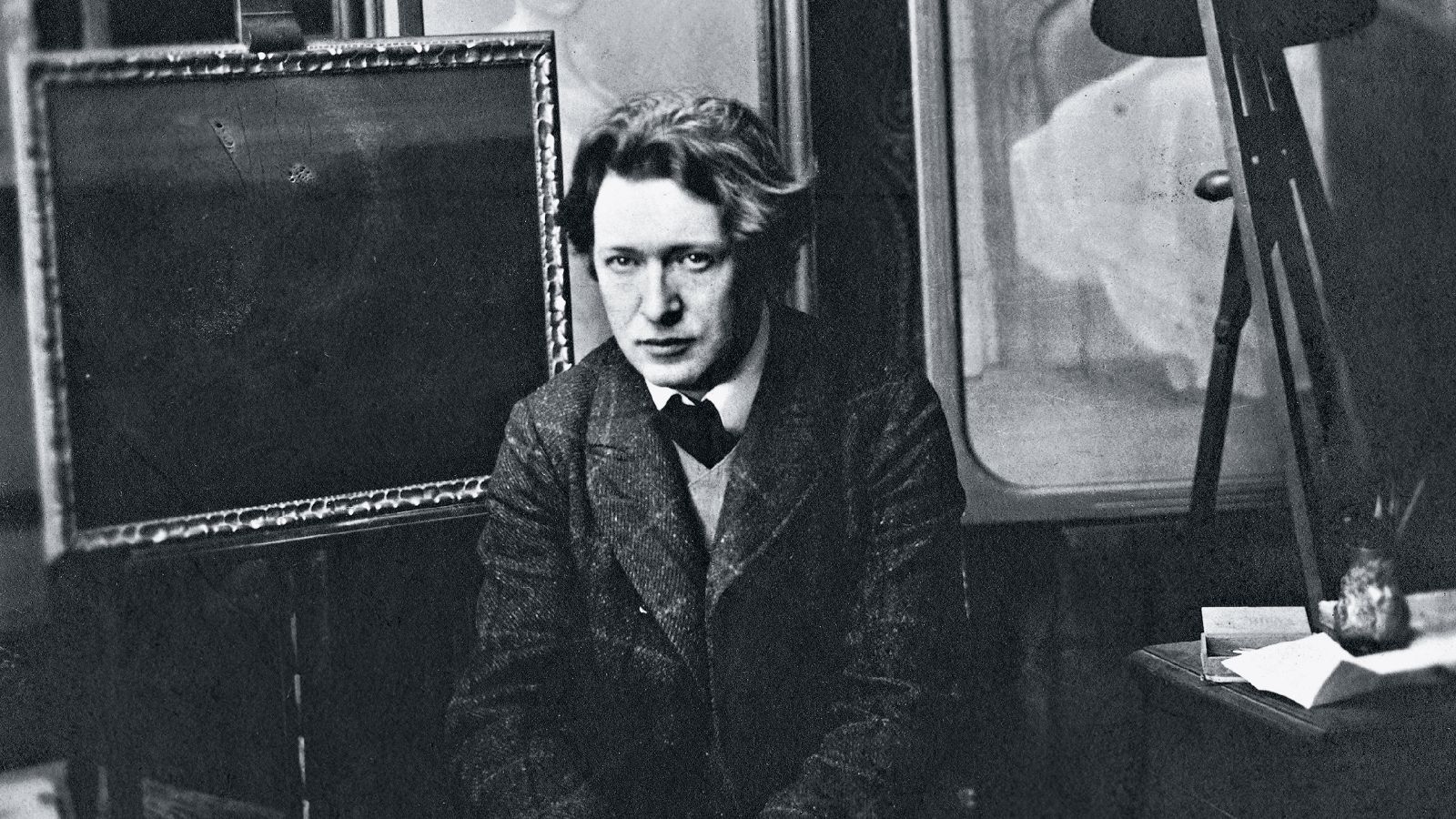

Leonard Slatkin: Then the nurse asked, ‘how do you write music?’

mainThe conductor, recovering from heart surgery, is having close encounters with the medical community.

After a couple days, I was told that it was time to take a little walk in the hallway. This was not easy, considering that I was hooked up to various medical devices, not to mention the pain from the surgery. There were others doing the same thing, all of us moving at the speed of the zombies in Night of the Living Dead. Most were accompanied by nurses and sometimes a friend or relative.

It was during one of these excursions that the person assigned to me for the day—they each take 12-hour shifts—asked me what I did for a living. I simply said that I was a conductor for symphony orchestras. And then came a question that was completely unexpected.

“How do you write music?”…

Read on here.

A couple of years ago I took a friend with a master’s degree in molecular biology to a symphony concert for the first time. The conversation after we got in our seats:

“So what’s on the program today?”

“Beethoven 5th”

“I didn’t know Beethoven had a great-great-grandson who is also a musician.”

A true story!

This story is certainly not true but it is nice.

A young music student was asked by his teacher in the first day of school how many symphonies Beethoven has written. The answer came quickly: “Two. The Fifth and the Ninth”.

Beautiful story. I love that Maestro did not give a speech about the difference between a conductor and a composer. Perhaps later she may have comfirmed on Google who was Leonard Slatkin.

Indeed. I can think of plenty of other conductors who would have delivered the nurse the full “Do You Know Who I Am?” treatment.

Tchaikovsky’s response when asked that question: “Sitting down.”

Overheard of couple leaving after outdoor Shakespeare festival perf of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” —

“Shakespeare sure uses a lot of quotes!”

I like that Maestro Slatkin explained that music is a written LANGUAGE. As such, ideally, children should be introduced to that language in their grammar school years. I’ve never met anyone who ever regretted learning how to read music.

Bravo.

Agree and I think there are many people (including me) who regret not having continued learning music.

I DID learn to read music, and I regret it. Printed music is a crutch to me, it helps me avoid using my ears. And certainly printed music CANNOT capture the nuances, such as rhthymic, that makes music great, particularly genres that heavily emphasize rhythm, such as jazz. I’m not totally against teaching reading – I would make it maybe 25% of the curriculum, with the remainder ear training – dictation, sight singing, transcription.

Patrick, I would consider those things part of a basic music curriculum as well (ear training – dictation, sight singing, transcription, etc.). I know what you mean!

Re TFA — Words words words, and “Cageian” words at that. I’d look to future with more optimism if LS had given her a little digital keyboard and the WTC instead.

I believe John Cage defined music (perhaps I’m paraphrasing a bit here) as an arrangement of sounds in time and space.

Leonard, those bass drum thwacks at the start of In The South, we rarely hear them. But I think the opening sounds better when they’re played loud. The late Edward Downs encouraged his BBC Philharmonic player to hit them so they had more weight and sounded out, but without being over the top. This opening apparently portrays the motion of the sea journey the Elgar’s made from Dover to Calais in December 1903.

Fascinating read. Thanks to maestro Slatkin.

Some years ago, my father-in-law was asked about his profession during jury duty.

The judge said, ‘Mr. ***** what do you do for a living?’ Response: ‘I’m a conductor.’

Judge: ‘Really? Which train?’

Overheard at a record store, “Why does this album say ‘The Late Beethoven String Quartets’? Everyone knows Beethoven is dead”

That’s better than, “hey, do you have that song by Beethoven, the one that goes . . . “

I would say his explanation was a bit over-complicated and perhaps more about the academics who write tedious soon-to-be-forgotten music than the real composers who have stood the test of time.