Slipped Disc book club: The author responds

mainFrom our moderator:

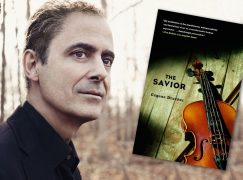

This second installment of the Fortnightly Music Book Club revolves around the first 5 chapters of The Savior, a novel written by Eugene Drucker, a founding member of the celebrated Emerson String Quartet. The book is a dark, often surreal novel centred around a young German violinist, Gottfried Keller, in the waning days of World War II. Many readers responded with questions, and Mr. Drucker will answer below. Please continue to submit questions via email to: Fortnightlymusicbookclub@

For those who have not begun reading it yet, the first five chapters of The Savior trace the experiences of Gottfried, a talented German violinist whose weak heart prevents him from serving as a soldier, during the final months of the War. We follow him on his assignments to play for the wounded and dying soldiers. He is dejected, apathetic and reluctant, and one morning he is driven by an SS officer not to the usual hospital but to a new assignment. He arrives at a concentration camp on the outskirts of town and is made to take part in a strange experiment probing the nature of the human soul. The Kommandant, surprisingly knowledgeable about classical music, orders Keller to perform four concerts over as many days to a select group of prisoners, ones who have been brought back from the brink of death. The aim is to investigate whether they can once again find hope through music.

Through a series of flashbacks, triggered by Keller’s feelings of guilt, we begin to see Keller more deeply. He is increasingly revealed to be a conflicted soul whose own past relationships with several Jewish musicians put him in jeopardy.

Reading ahead, we will begin to see a different side to the prisoners and to Keller himself, as the lives of the guards, the musician, and the prisoners become increasingly intertwined.

Eugene Drucker, violinist of the Emerson Quartet, has answered questions below. See you in a Fortnight!

– Your description of the Paganini Caprices 5, and 9 are riddled with evocative language such as hunting horns, scales hurtling down, fistfuls of chords, ricochet. Is it your intension to bring the brutality of the book into our ears with this music?

Answer: I would probably have described those two Paganini caprices with similar language, even if the setting had nothing to do with a concentration camp. In this chapter I was trying to demonstrate the incongruity of music and the brutality of the camp atmosphere. The contrast comes across more pointedly in the next piece on his first program: the Ysaÿe Sonata, which creates a soundscape full of vibrant color, so much at odds with the dead acoustics and the human misery and bleakness surrounding Keller as he plays. The deepest music in Keller’s four performances — the sonatas and partitas of Bach — is continually presented as incompatible with the situation in which he finds himself. He begins this series of concerts, this “experiment,” feeling totally alienated from his listeners and from himself as a performer. In the course of the novel, he and they come closer together, and he changes at least as much as they do.

– Ernst, a Young Jewish violinist and friend to Keller, is barred from playing the Brahms Violin Concerto because he is Jewish. Is this based on an actual event?

Answer: Yes. The character of Ernst is modeled on my father, Ernst (later Ernest) Drucker. Through a compromise, he was allowed to play (only) the first movement of the Brahms Concerto at his graduation concert from the conservatory in Cologne in 1933.

– How did you find the time to write a novel – you are one of the busiest performers alive. Were you compelled to write it?

Answer: I wrote the novel gradually over the course of many years, repeatedly revising the basic story, evolving stylistically through several versions and taking significant chunks of time away from the project. Yes, in a sense I felt compelled to write it, because the story was meaningful to me both as a performer and as the son of a refugee from the Third Reich. With my background as an English and Comparative Literature major at Columbia University, I also felt a general need to express myself in writing, in addition to my musical activities.

– Do you believe that music has the ability to heal or hurt, or to bring the listener or player to places we can’t reach any other way? Why do you play the violin?

Answer: I believe that music has the ability to heal in certain situations. Oliver Sacks demonstrated that patients with certain neurological deficits could be helped enormously by listening to music. It’s more of a challenge to imagine a situation in which music could hurt people. But music, and the musicians who perform it, can sometimes be manipulated for propagandistic purposes, a phenomenon that is ultimately harmful. An entire book has been written about the political uses that have been made of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony during the past two centuries. The beautiful slow movement of Haydn’s “Emperor” Quartet became the Austrian national anthem and later, unfortunateIy, the German anthem under the Nazis. Many people who are old enough to recall broadcasts of Hitler’s speeches have profoundly negative associations to that work.

I do believe that music can bring the listener to a plane of emotional or spiritual receptivity that is otherwise difficult to reach. I feel that I can sometimes achieve moments of deep connection with the core of the great music I am privileged to play. I hope that at least some audience members feel the same way at those times. Those are some of the most satisfying experiences of my professional life.

– Was there ever a real-life example of a violinist who played in a death camp? If not, is Keller your fantasy or your fear?

Answer: There were bands and orchestras in death camps, but as far as I know, they consisted of inmates, not visiting performers. The most famous one was in Auschwitz, led by the violinist Alma Rosé, the niece of Gustav Mahler. The function of such groups was to provide entertainment for the guards and administration of the camps, and to play while inmates were marched out the gates to their places of forced labor. So Keller is my fantasy, a sort of musical Everyman who is confronted with a painful moral dilemma and fails to rise above it. You could say that he is my “fear” as well, because he is emblematic of the ways in which even the noblest expressions of the human spirit could be distorted and perverted in the service of evil.

– Identifying the precise music that Keller plays adds realism–a musician would remember specific pieces–and constitutes the piercing detail, what Roland Barthes called the punctum, by which the reader identifies with the story. But would a completely different repertoire have changed anything in the plot or psychology of the novel?

Answer: Since I was writing about a solo violinist rather than a solo pianist, the choices of repertoire were much narrower. That made my task as storyteller considerably easier. Though there is music for unaccompanied violin that predates Bach, it’s unlikely that a mid-20th century violinist would have been familiar with it. There are a dozen fantasias by Telemann, but, while beautiful, they lack the complexity and emotional heft of Bach. Keller’s attempt to break the ice at the first concert with Paganini caprices fails, partly because of their technical difficulties (for him), but also because the type of virtuosity and celebration of the violinistic self that they embody feel painfully out of place in the camp. The sonatas of Ysaÿe may have been unlikely repertoire for a German violinist of that era, but not out of the realm of possibility; they provide a useful change of color, not only in the concert programs I was imagining but also in the descriptive language I was using. The two remaining pieces — a sonata by Hindemith, whose music had been condemned as “degenerate” by the Nazis, and an imaginary piece Keller himself had composed — are meant to illustrate the temptation an artist in the Third Reich might have felt to break the rules and experiment with less traditional music. In the second chapter I refer to Keller’s attraction to “the jagged edges of Hindemith, Bartok and Berg.” The Bartok Solo Sonata, one of the most difficult pieces for unaccompanied violin, was a staple of my own programming during my 20s. I felt a strong affinity for that piece, and would have liked to offer my protagonist a chance to play it. Its emotional sweep and sonic palette would have provided a lot to write about in the imaginary setting of Keller’s performances. However, the Bartok Solo Sonata was completed in the U.S. in 1944, and would have been unavailable to a German violinist during the war.

A different repertoire might well have changed the plot or psychology of the novel, and I chose the pieces for the four concerts carefully in order to reveal and explore Keller’s psychology and to move the plot forward.

– How far would you take the idea of Keller’s complicity? Does it extend to any musician who remained in Germany and performed during the war?

Answer: Though I intended Keller’s situation and his actions to be symbolic of the passivity of a large swath of the German population — a gray area in the broad spectrum between active collaborators and heroes of the Resistance — I would not say that any musician who remained in Germany and performed during the war was complicit in the horrors of the Holocaust. My father often pointed out that Wilhelm Furtwängler — who was subjected to international boycotts in the late 1940s, especially in the U.S. — had kept a number of Jewish musicians in the Berlin Philharmonic for as long as possible after the Nazis came to power. Furtwängler also protested against the Nazi ban on performances of Hindemith and clearly chafed against many of the artistic restrictions imposed upon him by the regime. But he will always remain a somewhat ambiguous figure because of the inevitable compromises he made in order to stay in Germany and continue as an active performer.

Thank you for joining us, and see you in two weeks.

Comments