First reviews are trickling in. Here they are, more or less in order of online appearance:

New York Classical Review:

This was the role debut Metropolitan Opera audiences have been dreaming of for more than a decade: on Saturday night, in a performance that was sold out months in advance, Anna Netrebko sang her first Tosca. The reigning diva of the opera world finally appeared as the greatest diva written for the stage.

Leading the season’s second cast in the new production by David McVicar that opened on New Year’s Eve, Netrebko gave a sensational performance. As ever, her soprano is dark and powerful, especially in her viscous, smoky middle range. Her top is as focused as it has sounded in years, soaring to majestic heights in “Vissi d’arte”; the passionate lament of Act II was breathtaking for both the passion of its delivery and the precision of its phrasing. The urgent piano singing in her plea after the aria was if anything even more affecting, a dramatic detail that completed the scene…

Poison Ivy:

So … how did the performance stack up against the hype? Pretty well, all things considered. Anna Netrebko is a Superdiva and Tosca is a Superdiva and the singer and the role were well-matched both musically and temperamentally. Netrebko’s voice has grown so much in volume and richness but lost a lot of flexibility. I saw a recent video of her Lady Macbeth in London and while it was exciting she struggled in the passagework of the role. Tosca makes no such demands. It allowed Netrebko to do what she does best, which is flood the auditorium with huge waves of sound. And her instrument is still a miracle. You can quibble with the suspect pitch, mushy diction, weird dipthonged vowels, and occasionally loosened vibrato. But to have a voice that can sing high, sing low, can fill any house with surround sound stereo volume, and with a gorgeous, plush timbre to boot — that’s God’s gift.

photo (c) Ken Howard/Met

Kurier (Vienna):

Anna Netrebko als Tosca – das ist wie ein Meisterwerk in einem Museum, das jeder sehen will und bei dem sich wohl nur die wenigsten Gedanken über den Kontext oder die Hängung machen.

Aber was macht Netrebko so besonders in gerade dieser Rolle? Sie war ja zuletzt auch als Aida in Salzburg extrem erfolgreich, als Maddalena di Coigny in „Andrea Chénier“ an der Scala oder als Elsa in „ Lohengrin“ in Dresden, als Lady Macbeth in München oder als Leonora im „Trovatore“, an vielen Häusern und auch in Wien. Die Antwort lautet: Sie singt die Tosca exakt zum richtigen Zeitpunkt. Viele wagen sich zu früh an diese Rolle und müssen sich in einem Gewaltakt bis zum Finale, zum Sturz von der Engelsburg, retten. Andere singen die Tosca noch zu spät, zu dramatisch, mit scheppernder Stimme. Netrebko, schon bei ihrem Erscheinen auf der Bühne mit Auftrittsapplaus bedacht, nimmt sich der großen Puccini-Diva am Zenit ihrer Karriere an (wobei Zenit? Wer weiß, was bei ihr noch kommt).

Parterre.com:

Feminine and vulnerable yet mercurial and implacable, Netrebko’s Floria Saturday night was already an astonishingly complete realization of a quintessential diva role she initially swore she would never do and since has suggested she doesn’t particularly like. I don’t much care for Tosca either, but Netrebko’s been absent from the Met for a year so I along with an eager, jam-packed house welcomed her back with open arms and hearty bravas.

New York Times (Tommasini):

Ms. Netrebko knew what she was doing. She was a magnificent Tosca. From her first entrance, Ms. Netrebko, one of the opera world’s genuine prima donnas, seemed every bit Puccini’s volatile heroine, an acclaimed diva in the Rome of 1800, seized in the moment with jealous suspicions over her lover, the painter Mario Cavaradossi. As she hurled accusations at Mario — Why was the church door locked? Who were you whispering with? I heard a woman’s rustling skirt! — it took a couple of minutes for Ms. Netrebko’s voice to warm up fully. By the time Tosca, having pushed doubts aside, beguiles Mario into a rendezvous at his villa that night, Ms. Netrebko’s singing was plush, radiant and suffused with romantic yearning.

We understand that a member of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra has been sacked from his lecturer’s post at the University of Music and Performing Arts and suspended from playing in the orchestra. The man is not being named while investigations continue.

The Vienna State Opera and the Vienna Philharmonic tonight issued the following statement:

The University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna informed us about their immediate dismissal of a lecturer, a member of Vienna State Opera Orchestra and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. We immediately started looking into the case and collecting any information in relation to this message, which we received with great surprise and regret. Until the facts have been clarified, the management of the Wiener Staatsoper has consensually released the musician from his duties for the time being. The Vienna Philharmonic is sharing this measure.

COMMENTS: Please do not mention the name of any player in the Vienna Philharmonic.

UPDATE: The player has been cleared by the Vienna State Opera and the Vienna Philharmonic.

press release:

Wigmore Hall Director John Gilhooly has invited Holocaust survivor and cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch to speak at a specially-programmed concert at Wigmore Hall following her recent address to the Bundestag in Berlin.

For this extraordinary event, Anita Lasker-Wallfisch – a survivor of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen – will describe her life story and the importance of learning from one of history’s darkest chapters. She is joined on stage by her son, the acclaimed cellist Raphael Wallfisch and the pianist John York for music by Bloch, Ravel and Korngold.

The event will be filmed and live-streamed via Wigmore Hall’s website.

Gilhooly felt compelled to bring Anita Lasker-Wallfisch’s message to London saying:

“After I saw Anita Lasker-Wallfisch’s address to the Bundestag, I felt it had to be heard in London, so I invited her to give the address in English at Wigmore Hall. As a non-Jewish leader working in the arts, I feel it’s necessary to give a public platform wherever possible to highlight the dangers of anti-Semitism, and I am puzzled as to why other non-Jewish voices have yet to speak out. After all, the Jewish diaspora has done so much for this country, in the arts, sciences, politics, medicine and not least philanthropy. Anita’s words are so important to hear, as history has shown, time and again, that where anti-Semitism, racism and extreme views are on the rise, dark times are usually never far behind. Combined with powerful and appropriate music, this very special event is presented as a timely lesson for all generations and creeds.”

In her address to the Bundestag, Anita Lasker-Wallfisch said:

“Anti-Semitism is a virus which is two thousand years old and apparently incurable […] No other genocide is as comprehensively documented as the Holocaust. And yet there are still the deniers, people who claim that all the accounts are fabricated and that the Holocaust never happened […] There are no excuses and no explanations for what happened all those years ago. All that remains is hope: the hope that ultimately, one day, reason will prevail.”

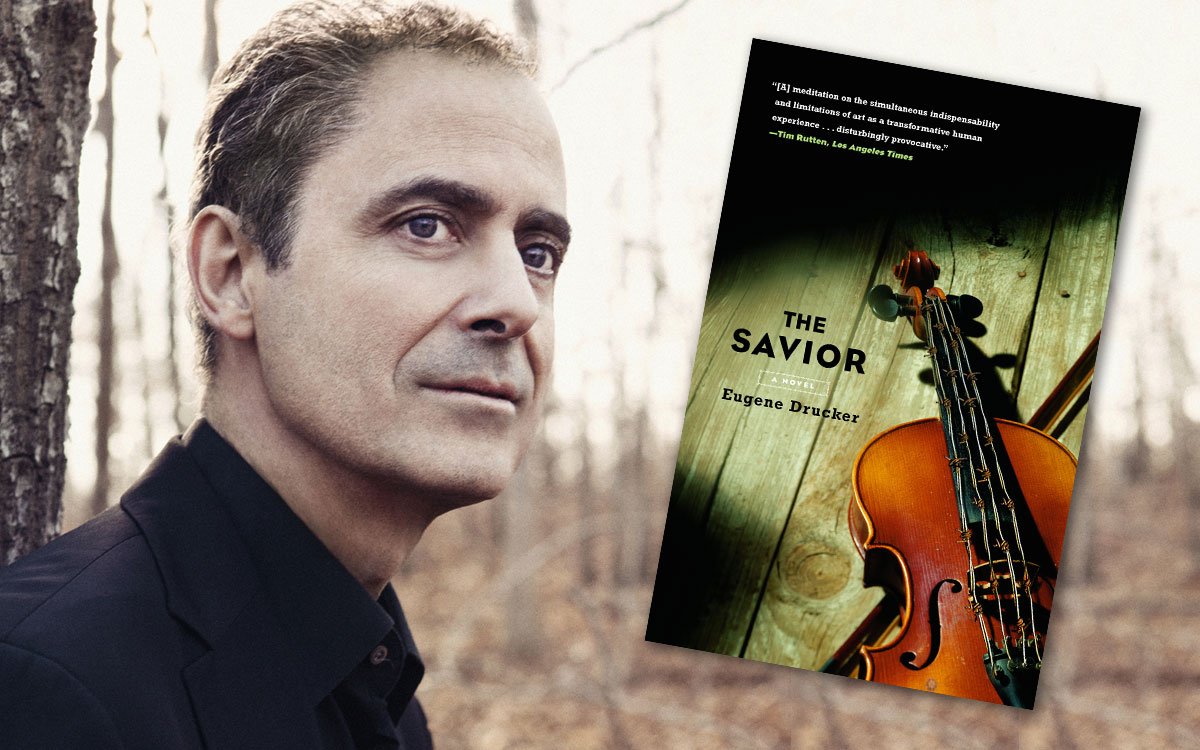

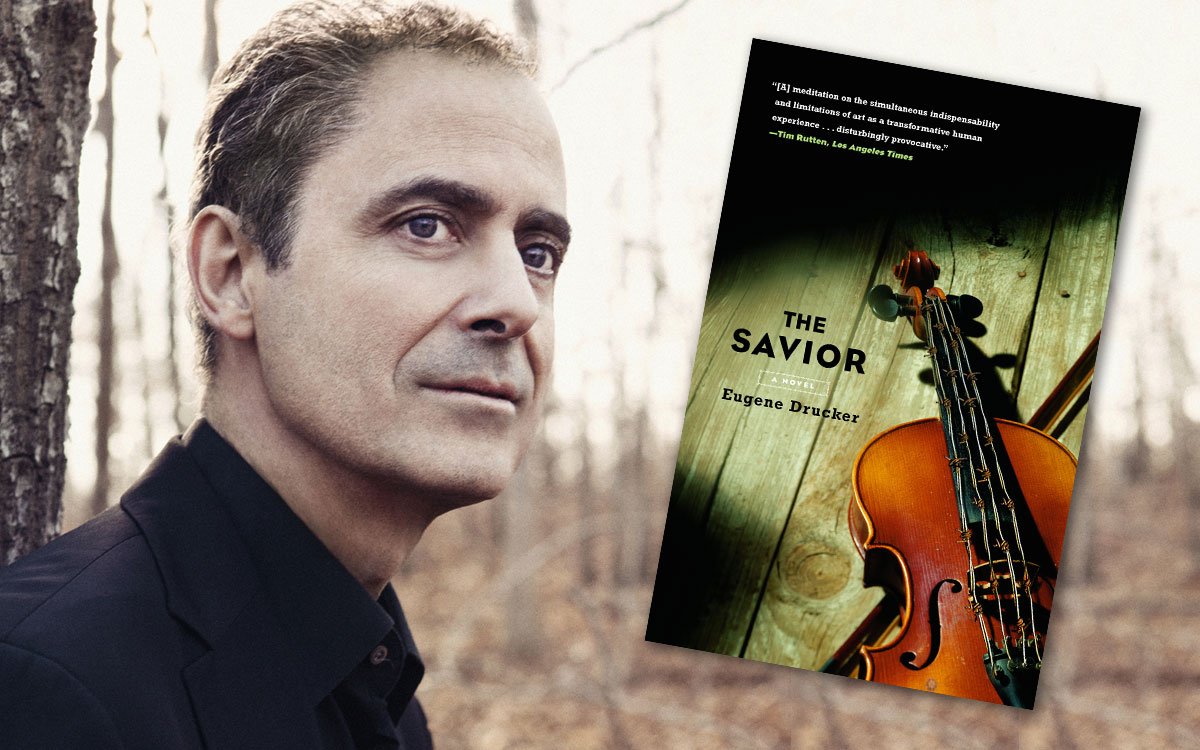

This third instalment of the

Fortnightly Music Book Club revolves around chapters 6 through 11 of

The Savior, a novel written by Eugene Drucker, a founding member of the celebrated

Emerson String Quartet. The book is a dark, often surreal novel centered around a young German violinist, Gottfried Keller, in the waning days of World War II. Many readers responded with questions, and Mr. Drucker will answer below. Please continue to submit questions via email to:

Fortnightlymusicbookclub@gmail.com. If you have interest in forming a brick-and-morter Fortnightly in your town, please write so we can find ways to connect.Keller, our violinist protagonist, is increasingly involved with the concentration camp. These layers of involvement are complex and intertwined – his relationship with the Kommandant, a somewhat sympathetic guard, and the prisoners (his audience). Keller is an unwilling part of the Kommandant’s experiment to see if prisoners’ hope can be revived through music, and as his concerts continue, the audience does begin to change, and Keller along with them.

Eugene Drucker, violinist of the Emerson Quartet, has answered this week’s questions below. We will have one more opportunity to explore The Savior, and if you would like to read ahead, the next selection will be “Gödel Escher Bach” lead by composer Daron Hagen, one month from now. See you in a Fortnight.

Question:

You say your father wrote to the Nazi paper, but the book doesn’t mention Ernst doing that — why?

Answer:

On page 41, Ernst tells Gottfried, “I’m going to write a letter to the editors, pointing out that Brahms dedicated his immortal German concerto to the Jew, Joseph Joachim, who helped him write the violin part.” A large part of the conversation between them from this point on involves Gottfried’s fear of the possible consequences, and his attempt to persuade Ernst not to write the letter. It’s true that I (as author) don’t confirm that Ernst really went ahead and wrote the letter. Actually it was not quite as dangerous in July 1933 to write such a letter as I made it seem, for the purposes of dramatization of the contrast and conflict between the two young men. My father never led me to believe that his writing the letter was an act of extraordinary courage, but it was undoubtedly an act of defiance.

Question:

What conclusion should we draw from the ant experience? (As a boy, Keller kills a handful of ants, and asks his parents why they didn’t hide from him)

Answer:

I believe that every human being has an innate capacity for anger and violence, as well as for good. Upbringing and culture, both within one’s family and in the society at large, contribute to the outcome of the struggle between these conflicting tendencies. Children often behave cruelly toward animals before they learn to empathize with the suffering of other creatures — before they can identify with the subjective experiences of animals and even of other human beings, rather than regarding them simply as objects. The unbidden memory of Keller’s childhood massacre of the ants is the first (largely unconscious) intimation of a link between him and the purpose of this camp.

Question:

In the Author’s Note at the end you say some of the bizarre moments in Keller’s performances for he inmates were based on your experiences playing in hospitals, psych wards, etc. Can you tell me more about your own experiences and whether your music made a positive change in the people you played for?

Answer:

In an alcoholics’ ward I was asked repeatedly to play The Flight of the Bumblebee, which was one of the few violin pieces that the patients were familiar with. When I replied that I couldn’t play anything I hadn’t prepared, this seemed to frustrate my listeners, one of whom turned her back to me and stared at the wall during my whole performance of music by Paganini, Ysaÿe and Bach. In a psychiatric ward, a young woman had fashioned a homemade mask out of some cloth. I was told by an attendant that this seemed to make her feel more secure in her interactions with other patients and staff. In a drug rehabilitation center for young women, I sensed that even without any background in classical music, my listeners were somehow open to the gestures, colors and emotions of the music. I can’t say whether my performances had lasting positive impact, as I didn’t follow up with subsequent visits to any of the six or seven facilities where I played.

Question:

Do you think Bach could have “done better” in depicting Judas’s despair, rather than writing a cheerful tune in G Major? (Pg 95-96)

Answer:

No, I don’t believe that Bach “could have done better.” But having played St. Matthew Passion three times in my mid-20s, and having performed the violin solo in that same aria each time, I often asked myself why Bach chose to represent the episode of Judas and his attempt to return the silver pieces in this particular way. The best answer I could come up with (as a non-musicologist) was what I offered on page 96: “ … he wants us to identify with Peter, but not with Judas. The aria isn’t sung from his point of view: we see him from the outside, so all we hear is the clink of coins.”

Question: Have you had deep musical experiences off the concert stage? (Page 117)

Answer:

As a listener, I have sometimes been very moved by all sorts of music, both in concerts and when listening to recordings in my own home: Lieder, opera, symphonic works and chamber music. The performances would have had to be great, and I would have had to be in a receptive mood. The criteria that allow for a peak experience don’t always line up perfectly, but one tries as both performer and listener to achieve this heightened state from time to time. Sometimes in my car, during a long solitary drive, I’ve also felt the type of exaltation I’m describing (though never in heavy traffic!). Tears have come to my eyes — fortunately not to the extent where they dangerously blurred my vision — and chills have run up and down my spine. Beethoven, Brahms and Mahler symphonies particularly have had this sort of effect on me while I’m driving. And at those times I’ve felt profoundly grateful that such music exists, and that I’ve been privileged to learn about it and to be able to respond to it like that.

Thank you for joining us, and see you in a Fortnight.

Thomas Sleper retired this week after 25 years at the head of the Frost Symphony Orchestra at the University of Miami.

He made it a rare bastion of American and English 20th century music.

Read here.

From the Lebrecht Album of the Week:

How many times have I told you not to buy a record for its cover? Well, this one justifies the purchase. The image shows the central square of a small town in Poland in the 1960s, a place where nothing ever happens yet everything is closely watched. The image has been colourised for added artificiality. It is stifling, cloying, vividly reminiscent of the oppressive dullness of Communism.

The music is made to match….

Read on here.

And here.

The film, television and stage composer Howard Goodall has issued an extensive forensic examination of the economic prospects for British music and society after Brexit. It does not make comfortable reading.

Two samples:

Music is not a subsidiary, luxury, minor industry for the UK. We are the second biggest provider of music to the world after the USA. Music is of enormous benefit to us as a country. That is a fact, not an opinion. Nor is it special pleading. For a modern, developed country to deliberately, wilfully strangle one of its lead exporters is bordering on insane. Indeed, the Creative Industries as a whole are the fastest-growing sector in our economy, worth last year just under £100bn to our national coffers (to put that in context, in 2016 the NHS cost us £115bn). The Creative Industries Federation are deeply concerned about the knock-on effects of Brexit on this sector and have published their concerns …

Even if the economic arguments for this folly were sound, the depravity of the ‘hostile environment’ it has brought in its wake, the race-hate, the bullying, the targeted governmental callousness and breath-taking ministerial arrogance would be enough to render it an experiment bound to fail on a social level alone. A stench of recrimination and intimidation has begun to seep from the pronouncements of Brexit spokespeople in recent months, from John Redwood MP’s threat to ‘punish’ businesses for speaking out against the dangers of Brexit to James Cleverly MP’s tweeted comparison of (brilliant) satirical comedy writer David Schneider to his dog, for daring to question the economic case for Brexit. Elected politicians who stoop to threats and insults demean their office and public discourse in general. Is this the Britain we should expect after Brexit?

Read on here

The Staatstoper has issued a Twitter explanation for sacking the French star Julie Fuchs:

The Hamburg State Opera regrets that we are not allowed to fill the soprano Julie Fuchs in the role of Pamina in the Hamburg production of the „Magic Flute“. After a thorough examination, it is not possible to change the staging so that there is no danger for the expectant mother and at the same time the core of the production of Jette Steckel remains. There are a variety of physically demanding scenes in this production, including several flight scenes, which are prohibited in principle for pregnant women. The legal situation for the protection of the expectant mother is clear and we will never take a health risk, even if only a risky scenic action could take place on the stage,”

(signed) Tillmann Wiegand, Director of Artistic Management at Hamburg State Opera*.

Just a matter of health and safety? Here are some online reactions:

Speranza Scappucci, conductor: Absurd and unacceptable.

Julia Bullock, soprano: Unless the production would be dangerous for her unborn baby, because of stage direction (like floating around in a harness for hours during ariel work) I cannot IMAGINE why or on what grounds a company has for withdrawing a pregnant woman from an opera. Again, without all the facts I won’t say defaming things, but the decision to perform or not should be one of the soon to be mother!

Michal Bet-Halachmi, clarinet: Isn’t there a law against this?

Brent Calis, photographer: What year is this?

Basia Jaworski, critic: If it’s so dangerous, sack the director, not the singer.

Denis Comtet, conductor: It is unacceptable and scandalous, but it is quite characteristic of contemporary western society on the mother and the unborn child…

Marina Comparato, mezzo-soprano: Una nostra collega (e che collega!) discriminata in quanto incinta di 4 mesi! Vergogna!…

* Original German text:

Wir bedauern sehr, dass sie die Sopranistin Julie Fuchs in der Partie der Pamina in der Hamburger Inszenierung der „Zauberflöte“ nicht besetzen darf. Es ist nach eingehender Prüfung nicht möglich, die Inszenierung so zu ändern, dass keinerlei Gefahr für die werdende Mutter besteht und gleichzeitig der Kern der Inszenierung von Jette Steckel bestehen bleibt. Es gibt in dieser Inszenierung eine Vielzahl von körperlich sehr fordernden Szenen, darunter mehrere Flugszenen, die für schwangere Frauen prinzipiell verboten sind. „Die Rechtslage zum Schutz der werdenden Mutter ist eindeutig und wir gehen in keinem Fall ein gesundheitsgefährdendes Risiko ein, wenn auch nur im Ansatz riskante szenische Aktionen auf der Bühne stattfinden könnten.“, Tillmann Wiegand, Betriebsdirektor