The night Arnold Schoenberg turned down an Oscar nomination

mainE. Randol Schoenberg, the composer’s grandson, has found a wonderful letter from the old man, declining a chance to introduce one of the Oscar winners in 1938. The winner in question was Charles Previn, for Best Original Music Score, One Hundred Men and a Girl

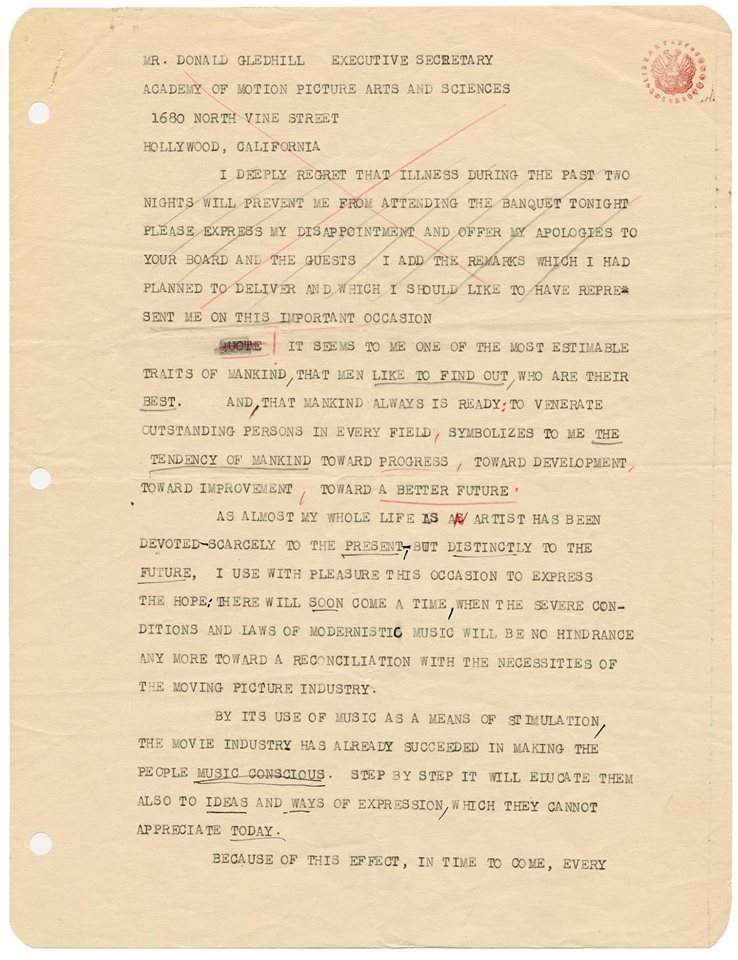

The letter reads as follows:

Mr. Donald Gledhill, Executive Secretary

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science

1680 North Vine Street

Hollywood, California

I deeply regret that illness during the past two nights will prevent me from attending the banquet tonight. Please express my disappointment and offer my apologies to your board and the guests. I add the remarks which I had planned to deliver and which I should like to have represent me on this important occasion.

It seems to me one of the most estimable traits of mankind, that men like to find out, who are their best. And, that mankind always is ready to venerate outstanding persons in every field, symbolizes to me the tendency of mankind toward progress, toward development, toward improvement, toward a better future.

As almost my whole life as an artist has been devoted–scarcely to the present,–but distinctly to the future, I use with pleasure this occasion to express the hope: there will soon come a time, when the severe conditions and laws of modernistic music will be no hindrance any more toward a reconciliation with the necessities of the moving picture industry.

By its use of music as a means of stimulation, the movie industry has already succeeded in making the people music conscious. Step by step it will educate them also to ideas and ways of expression, which they cannot appreciate today.

Because of this effect, in time to come, every outstanding man in this field will deserve the title of pioneer of culture.

Therefore I congratulate most heartily the man whose Universal Picture Company picture “One Hundred Men and a Girl” has been chosen by so great a majority of votes to be recognized as the author of this years best musical score.

Arnold Schoenberg

116 N. Rockingham Ave.

West Los Angeles.

Telephone: W.L.A. 35077

A time when class, grace, eloquence and civility ruled. Not anymore.

Arnold has just gone up in my estimation 100%. There must have been nobody that year who was writing sentimental schlock with mawkish and sentimental lyrics. I don’t watch the tired spectacle of virtue-signalling which has become modern entertainment award ceremonies. Back in the days of the Freed Unit of MGM and the excellent music of the greats of American musical theatre in some pretty stunning film musicals the choices were obvious for prizewinners. Excellence was the order of the day. Talent abounded. Alas, not any more.

It should be noted that Previn won the award as head of the music department, not as the composer. This was apparently the norm for a time where the producer got the credit.

There were two new songs and the rest of the score were taken from classical music, some conducted by Stokowski, some uncredited. The works included Tchaikovsky’s 5th, Berlioz’s Rakoczy March, and Wagner’s Lohengrin. Far from looking forward, rather it emphasized already that only music a hundred years old mattered. The selection of almost century-old classics beat out new film scores from Steiner, Newman (2 films), and Disney’s multi-composer Snow White.

Feedback from this likely led to the change in 1939 where “original” actually had to mean that.

I felt a similar “huh?” from the Grammys in 1991, when “Unforgettable”, a song from the late 40s, won “best song” award which normally goes to the songwriters. It basically told 2 generations of songwriters that they’ll never be as good as the songs your grandparents listened to, so why bother? I felt it very insulting.

“…Far from looking forward, rather it emphasized already that only music a hundred years old mattered.”

How much atonal, 12-tone music do you think there should have been in a Deanna Durban movie?

Hollywood was so often accused of being immoral and superficial, they may have wanted to note that they had something classic and durable in their bag of tricks as well.

https://youtu.be/TNJrwcS9u34

Well, I wasn’t expecting 12-tone (though it did come in the 50s with some scores from Rosenman, and even a bit of West Side Story)…I was just pointing out that “original score” meant something very different in 1938 to 1939 and today.

Had the rules of 1938 remained in place, Kubrick might have gotten an Oscar for score for 2001: A Space Odyssey. (Granted, not many knew that the works from Ligeti, or even the Strauss excerpt, were not made specifically for the film, but there we are).

And though we’re talking Schoenberg because of the context, 12-tone wasn’t the only composition style at the time, obviously. Korngold was about to give romanticism a shot in the arm in the film world that would never leave, while Disney’s composers, especially Frank Churchill, would remain influenced by impressionism (Debussy and Ravel) until the war changed the nature of the studio’s output. Copland was just about to hit his popularist peak, and neo-classicism was a movement with quite a lot of support.

My original post wasn’t meant to imply that film composers should have been 12-tone. It was simply a comment that an “original score” full of 50 to 100 year old classical works was deemed by the Academy to be the “best” among a field of contemporary film composers, thereby telling them (in parallel with the Grammies 55 years later) that their efforts would never be as good as the composers of the past.

In light of who won, and what that original score contained, Schoenberg’s intended comments have something a dark irony to them.

It turns out there were fourteen (!) nominees for Score that year. Anyone who lost had lots of company and probably didn’t lose any work over it.

I’m extremely doubtful that any lasting message was inflicted on Hollywood composers by this outcome. A perusal of Best Score winners over the years shows that many major talents would get their due for their original efforts.

I’ll also note that this was only the fourth year for the Score award. What made a great score was perhaps not as obvious then as it is now.

“A perusal of Best Score winners over the years shows that many major talents would get their due for their original efforts”

Which is pretty much what I said. There probably was some backlash over ‘original’ at the time, resulting in a change in the rules such that 1) the composer, not the producer, gets the award, and 2) it must be actually original, created for the film it was nominated for.

So no, it didn’t change the composers but it did change the awards.

Not the last time. Things change all the time in regard to feedback, such as how the Sound awards are divvied up (which makes no sense at all to an outsider).

“How much atonal, 12-tone music do you think there should have been in a Deanna Durban movie?”

Right. Because that was the only kind of music being written at the time.

Arnold Schönberg lived 11 doors down on the same street as O.J. Simpson, where the “bloody glove” was found after the double murder.

I have never been able to forgive the family for acquiescing in the relocation of Schönberg’s collection and archive from L.A. to Wien, an outrage.

It’s very weird to mention Arnold Schönberg and this other guy in one sentence. There is definitely no link. Because he was born in Wien it’s absolutely natural coming home after a very long time in cultural isolation…

Oh, you’re so funny. And original.

Although Arnold formed a friendship with George Gershwin and a bunch of intellectuals, it has to be said. The Arnold Schoenberg Centre in Wien is very good.

I doubt they met. 🙂

Why mention this? Brentwood is a des res in LA. Schoenberg died in 1951, when Simpson was 4, so I doubt he had bought the property yet.

If you tried hard enough I daresay you could find all sorts of undesirables who had lived, at some time or another, in proximity to where some more admirable sort lived. It would take a peculiar sort of personality to make such associations, though.

You appear to be conflating the return of Schoenberg’s archive to Vienna with Simpson. I seriously doubt it ever entered anyone else’s mind.

Paragraphs are to separate thoughts, are they not?

No, they are not. The last sentence of one paragraph should be a link to the next paragraph. It’s rather akin to creating a ‘long line’ in music. It’s also a basic lesson for people learning to write.

I’ll try bullets next time.

The home that Simpson lived in was non-existent when Schoenberg was alive. There were very few homes on Rockingham, mostly vacant lots.

OLASSUS SAYS: “I have never been able to forgive the family for acquiescing in the relocation of Schönberg’s collection and archive from L.A. to Wien, an outrage”

In fact, the University of Southern California had decided that USC was not “getting their bang for the buck” as they indicated on BBC radio. They, in effect, evicted the family. Happily, it now flourished in Vienna celebrating its 20th year.

http://www.schoenberg.at/index.php?lang=en

As I recall, the family could have vetoed the move and chose not to. It was a huge loss for Los Angeles.

As I recall, USC were prepared to throw the collection onto the street. Nobody in LA seemed bothered.

Someone should have called USC’s bluff until a new home, in L.A., was secured. There is no way that collection should have left.

Well, if it’s any ‘consolation’, a huge amount of materials and artefacts from the MGM Freed Unit of the 30s and 40s was destroyed – and that was reprehensible.

OLASSUS SAYS: “Someone should have called USC’s bluff until a new home, in L.A., was secured. There is no way that collection should have left.”

I agree that “someone should have” but no one did!

Sorry, Mr. Schoenberg, but the someone I was referring to was you. The family had a tough task thrown in its lap, but instead of slogging it out and securing a new home in Los Angeles, as civic pride would have dictated, the easy option was taken to send the material out of the United States in the knowledge it would be welcomed and safe.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gBAK-hEzM0w

There was a wonderful woman by the name of Clara Stuermann ( wife of Edward Stuermann) who I believe helped and spearheaded the collection when it was in L.A.

Arnold Schönberg was born, raised, and grew as an intellectual and creative musician in Vienna. For all its warts, Vienna was the city that helped make Schönberg the creative force he was. That city and not so far away Berlin, where Schönberg later taught, remain more devoted to his music than any like centers in the USA. Schönberg was not the first great composer treated poorly by the political failings of Austria. Should we disallow museums devoted to Franz Schubert in Vienna because Clemens Metternich ran a police state that refused the impecunious Schubert the right to marry his young love? After all, the probable reason Schubert died at age 31 was his being weakened by venereal disease.

In a liberal democracy, under the rule of law, the sins of a guilty father are not to be visited upon his innocent sons and daughters. If such guilt could be so transferred, would not the American history of slavery disqualify our country as well from having a center devoted to Arnold Schönberg?

When I worked at the School of Performing Arts at the University of Southern California during the initial set-up of the Arnold Schoenberg Institut, the Berlin government gave $100,000 to equip the Institute building. Using the moral standard of OLASSUS, the entire run of that operation from inception in 1974 until USC gave its considerably enhanced collection to Vienna in 1996 would have been morally tainted.

Vienna’s Arnold Schönberg Center has a budget many times larger than USC ever provided, even in its heyday, and now, after some twenty years running, it does exemplary work advancing the life, legacy, and relevance of Arnold Schönberg to the world today.

Schönberg will remain relevant for research and understanding of what happened musically in the last century, and therefore it is of great importance that the Schönberg Centre remains in Vienna as a monument to its history and cultural relevance, and provides material which throws a light upon S’s works and life. Schönberg was and always remained a Viennese.

Sadly, there is a link between O.J. and Schoenberg. Ronald Schoenberg, the composer’s son, was the judge who ruled on Simpson’s 1989 spousal abuse charge (five years before the murders.) Despite the photos of beaten Nicole, Schoenberg ruled O.J. should serve no jail time.

People don’t generally go to jail when found ‘not guilty’ thanks to the work of a tricky lawyer.

No there isn’t. This is about a letter from Arnold Schönberg (he was one of the most important composers in the last century!) and not about a letter or anything from his son Ronald Schoenberg. Got it?

FYI. The sentence in 1989 was the result of a plea bargain and recommendation by the City Attorney. The evidence, including photos, were not part of the record since there was no trial. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T06F_zYyRM4 and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gBAK-hEzM0w

And lest you offer criticism of the plea bargain, remember that Nicole Simpson had reconciled with OJ and retracted her claim of abuse. The DA couldn’t even convict OJ when he murdered her. Just imagine what problems they would have had trying to convict him of spousal abuse.

Back to Hollywood: It is well known that Schoenberg was involved in discussions to write the score for The Good Earth (1937) but demanded total authority over its use. He also wanted $50,000. No dice.

Now that’s a collaboration I would like to have seen. Irving Thalberg had just died when that film was released and the ‘fortunes’ of MGM were somewhat unclear.

I should say “when that film was being made”.

The letter says that Schönberg hoped that through the developments of the genre, the movie theatre, the barriers that still hindered the understanding of progressive music (like his) would, at some stage in the future, be overcome, so that the public would finally begin to understand the real music of their own time (like his), and finally be allowed to share in the progress of the times, the REAL times. The whole thing merely reveals the progressivist thinking of Schönberg and the sad misunderstanding he suffered from concerning ‘the movie’. Obviously this ‘One hundred men and one girl’ is one of those sentimental dragons dragging ‘oldfashioned’ music in its wake, including a ‘Russian’ conductor who forgot his accent.

This little speech is actually a put-down of the Previn award, notice that he avoided even mentioning the winner’s name, and his references to the whole silly production in corporate terms. Its disdainful drift would have been rudely obvious in the day, that’s how educated people insulted one another. The headline was, My day will come.

And it did! Except that his style of composing was published and promoted in the movies to signify & enhance fright, creepiness, not-right-ness in general. And there, amongst the broad masses, it has remained.

Yes, and what an irony this is.

It’s sad that (apparently) the son (Larry Schoenberg) of one of the great figures of music posted on this thread and we’re talking about drivel like O.J. Simpson.

Last year, I made a YouTube compilation for those who would prefer or find it necessary to have melodies to hum with or whistle (with tongue in cheek) to the works of Arnold Schoenberg. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BFD46uUQwGM

I ABSOLUTELY ADORE this arrangement – and all things Wienerisch, it has to be said.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yR94CiqtFLs

Comparing S’ early works with his later ones merely reveals the sad deterioration of an organic musical language into cramped, forced attempts to ‘speak’ through a machine.

http://subterraneanreview.blogspot.nl/2017/05/comprehensibility.html

Or maybe it only reveals something about the person doing the comparing.

Indeed, it may show a true understanding of Schoenberg’s achievements. Or at least: an alternative opinion to received wisdom which has accepted the theories of S and his circle as orthodoxy.

One can still have the greatest respect and admiration for S’s wide-ranging imagination and intelligence, and still object to the tragic developments in his thinking and composing. I believe he stopped being a composer of genius with opus 23 and everything that followed, and there are good arguments for it. The awful and misconceived convention to call S and his two pupils the ‘Second Viennese School’, in an attempt to give their works an academic aura, says it all. S was, in a deep sense, a traditionalist composer, longing for the greatness of Beethoven’s and Brahms’ music, but being captured by the 19C scientific belief of ‘progress’. He had the talent to restructure the tonal tradition to his own personal taste, as his 1st Chamber Symphony demonstrates, but his intellect – infected with progressiveness – would not let him. His tragedy is not better expressed than in the 2nd piece of the Fuenf Orchesterstuecke: ‘Vergangenes’. What he ironically called ‘die blumenreiche Romantik’ was the locus of his real artistic soul, that is why he could weep over it so eloquently:

ww.youtube.com/watch?v=dwnBAtpqOJw

PS:

ww.youtube.com/watch?v=dwnBAtpqOJw

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dwnBAtpqOJw

Easy to make broad pronouncements; harder to back them up. Explain again why each and every one of these works fails your test for “a composer of genius.”

op. 24 Serenade for clarinet, bass clarinet, mandolin, guitar, violin, viola, ‘cello and baritone voice (4th Movement: Sonnet of Petrarch)

(1920–1923)

op. 25 Suite for piano (1921–1923)

op. 26 Quintet for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon and horn (1923–1924)

op. 27 Four pieces for mixed chorus (1925)

op. 28 Three satires for mixed chorus (1925–1926)

op. 29 Suite for piano, piccolo clarinet, clarinet, bass clarinet, violin, viola, and ‘cellouite (1925–1926)

op. 30 Third string quartet (1927)

op. 31 Variations for orchestra (1926–1928)

op. 32 “From Today till Tomorrow”, opera in 1 act (Text by ‘Max Blonda’, recte Gertrud Schönberg) (1928–1929)

op. 33a

& b Piano Pieces (1929 / 1931)

op. 34 “Accompaniment to a Film-Scene” (1929–1930)

op. 35 Six pieces for male chorus a cappella (1929–1930)

Moses und Aron. Opera in Three Acts (1926–1932)

Konzert für Violoncello und Orchester (D-Dur) nach Matthias Georg Monn: Concerto per Clavicembalo (1932–1933)

Konzert für Streichquartett und Orchester (B-Dur) nach Georg Friedrich Händel: Concerto grosso, op. 6 Nr. 7 in B-Dur (1933)

Suite in olden style for string orchestra (1934)

op. 36 Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (1934–1936)

op. 37 Fourth String Quartet (1936)

Johannes Brahms: Piano quartet g minor, op. 25 for large orchestra (1937)

op. 38 &

op. 38b Chamber symphony No. 2 (1906–1939)

op. 39 Kol Nidre for speaker, mixed chorus and orchestra (1938)

op. 40 Variations on a Recitative for Organ (in D) (1941)

op. 41 Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte (Lord Byron) for String Quartet, Piano and Reciter (1942)

op. 42 Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (1942)

op. 43a

& b Theme and Variations for Full Band (Orchestra) (1943)

op. 44 Prelude for Mixed Chorus and Orchestra (1945)

op. 45 String Trio (1946)

op. 46 A Survivor from Warsaw for Narrator, Men’s Chorus and Orchestra (1947)

op. 47 Phantasy for Violin with Piano Accompaniment (1949)

op. 48 Three Songs for low voice (1933)

op. 49 Three Folksongs for mixed chorus a cappella (1948)

op. 50A “Thrice a Thousand Years” for mixed chorus a cappella (1949)

op. 50B Psalm 130 for Mixed Chorus a cappella (six voices) (1950)

op. 50C Modern Psalm, for speaker, four-part mixed chorus and orchestra, unfinished (1950)

To RS:

It is not difficult to ‘back them up’. First, there is the aural experience of small snippets that circulate within a static field and that don’t make sense; second: there is a serious theoretical problem with the idea of the chromatic, equalized field (with practical problems as a result): it is a physical fact that different intervals have different wave ratios which are immediately perceivable by the human ear (the art of piano tuning is based upon this practical fact). Hence the conflict between Schoenberg’s and Berg’s musical intentions and the frustrations of these intentions created by the confines of ‘the system’. In Schoenberg’s ‘free atonal period’ the dissonances do work because the style is referring all the time to the symphonic repertoire it descends from, and they are not hindered; hence the effective expressivity of most of these pieces. The 12-tone system freezed all of that. In the orchestral Variations the problem is obvious: gestures from the earlier symphonic repertoire battle against entirely artificial constraints and the effect is some ‘lava’ of static despair. It is all explained (among other things) in this book, chapters 2 & 3:

http://www.amazon.com/Classical-Revolution-John-Borstlap/dp/0486814483

Obvious from your response that you haven’t even listened to most of the works.

During his years in Los Angeles, Schoenberg barely eked out a living. LA was just the destination for many intellectuals fleeing Hitler, and AS always seemed an odd fit there. Most of his greatest music was not written there, and by the time the collection was taken and moved to Vienna, he was a mostly forgotten footnote in LA. I lived in Los Angeles during those years and remember not being surprised.

That said, Vienna seems like a much more fitting repository for this collection.

Composed in Los Angeles:

op. 36 Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (1934–1936)

op. 37 Fourth String Quartet (1936)

op. 38 &

op. 38b Chamber symphony No. 2 (1906–1939)

op. 39 Kol Nidre for speaker, mixed chorus and orchestra (1938)

op. 40 Variations on a Recitative for Organ (in D) (1941)

op. 41 Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte (Lord Byron) for String Quartet, Piano and Reciter (1942)

op. 42 Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (1942)

op. 43a

& b Theme and Variations for Full Band (Orchestra) (1943)

op. 44 Prelude for Mixed Chorus and Orchestra (1945)

op. 45 String Trio (1946)

op. 46 A Survivor from Warsaw for Narrator, Men’s Chorus and Orchestra (1947)

op. 47 Phantasy for Violin with Piano Accompaniment (1949)

op. 48 Three Songs for low voice (1933)

op. 49 Three Folksongs for mixed chorus a cappella (1948)

op. 50A “Thrice a Thousand Years” for mixed chorus a cappella (1949)

op. 50B Psalm 130 for Mixed Chorus a cappella (six voices) (1950)

op. 50C Modern Psalm, for speaker, four-part mixed chorus and orchestra, unfinished (1950)

Of these, the Kol Nidre, the Ode to Napoleon and A Survivor from Warsaw are the best, in spite of the 12-tones system – which he had not needed anyway.

The 2nd Chamber Symphony was begun immediately after the 1st one, somewhere in 1907, but left unfinished. In the thirties he took it up again, in a mood of nostalgia, as he explained in an interview at that time: he always regretted that he had not developed that style further because he felt there still were many possibilities there to be explored. But the 2nd lacks the ease and the inspiration of the 1st, in my opinion.

What a silly response. It’s ok if you don’t like or understand the music. It’s not ok to pretend that your personal prejudices are important enough to share with the rest of the world.

@ Randy S: I think it’s Your response that is rude and thoughtless.

Schoenberg was my main subject in my Cambridge days, studying with Alexander Goehr, the son of Walter Goehr who was a personal friend of Schoenberg. A. Goehr was (is) a Schoenberg expert, growing-up with Schoenberg’s music, his ethos and theories, and introducing modernism in England in the sixties and seventies. A. Goehr’s thinking was very close to Schoenberg’s as there obviously was a deep affinity, which could be traced in Schoenberg’s writings. Naturally, A. Goehr’s musical thinking (he is also a composer) suffered from the same type of flaws as Schoenberg’s, so: studying the subject’s material with someone who represented that line of thinking and had been so close to the sources and mentality, offered the best possible understanding of what inspired and what hindered the great (Viennese) man.

As for the 2nd Chamber Symphony: this interview quote can be found in: ‘Arnold Schoenberg; oder der konservative Revolutionaer’, by Willi Reich, published by Verlag Fritz Molden, Wien,1968, page 307. The interview was a written one by German psychologist Dr Julius Bahle in 1931.

John Borstlap, let me know when you’ve actually listened to all of the Schoenberg works you insist on judging. Your music has changed over the years and I am sure your ear has too. You might want to listen again if you haven’t in a while. I went to your website and was enjoying your music . . . almost as much as the works you were trying to imitate. http://johnborstlap.com/audio/

If you had listened carefully enough, you could have noticed Schoenberg’s influence in the ‘Sinfonia’ fragment, and also the clear differences with stylistic models (which ones? there are no clear models). Critique and admiration can go together, concerning different works. And yes, I listened to most of the works you mentioned, but I am as stubborn in my views as AS was, and more practical.

“Hey Arnie! Lookin’ great tonight! Who are you wearing?”

Korngold and Schoenberg carried on a somewhat polemical correspondence during the LA years, I’ve seen it described as friendly/polite but pointed on K’s part, concerning Music and its future.

I’d love to read this. Does anybody know if and where it can be found?

In the correspondence database at schoenberg.at, I only see one letter to Julius Korngold. I don’t think there was any correspondence with EWK.

October 12, 1944

Dr. Julius Korngold

1606 N. Curson Avenue

Hollywood,

Los Angeles 46, Calif.

Verehrter Herr Dr. Korngold:

Es ist schade, dass mein Vortrag “Komposition with twelve tones” den ich vor ein paar Jahren hier an der University of California at Los Angeles gehalten habe, noch nicht im Druck erschienen ist. Ich glaube, er ist imstande, wenigstens die theoretische Bedenken gegen mein Komponieren zu beseitigen.

Natürlicherweise kann er nicht das Ohr meiner Hörer bekehren. Nur vielfaches Hören und Wille zu glauben kann mir darin helfen–und soweit habe ich ja hier in Amerika aufgeben müssen. Nicht einmal “einfaches Hören” wird hier ermöglicht!

Mein Vortrag stützt sich in der Hauptsache auf einer neuen Ansicht über die Funktion der Dissonanz. Ich habe schon in meiner Harmonielehre die Dissonanzen als “fernerliegende” Konsonanzen definiert. Das heisst: während der Verwendung der “näherliegenden” Dissonanzen, der sogenannten Konsonanzen, in historischer Zeit keine Beschrä[n]kung auferlegt war, konnten fernerliegende Konsonanze, die Dissonanzen, wenn überhaupt, so nur unter gewissen Bedingungen verwendet werden. Diese Bedingungen waren solcher Natur, dass die Auffassbarkeit der “sinnstörenden” Klänge erleichtert wurde durch Benützung dessen, was ich “konventionalized[!] formulas” nenne. Es sind dies Formeln, die schliesslich jeder verstehen konnte; in denen (durch Vorbereitung und Auflösung, durch durchgangsweises Auftreten oder in Manieren) der zusam[m]enhangunterbrechende Klang als etwas Vorübergehendes, seine konsonante Umgebung als das Bleibende, Grundlegende dargestellt war.

Die Geschichte zeigt uns dass das Gehör schliesslich imstande war (wie “die Elektrische”) auf die “Schutzvorrichtung” zu verzichten. Oder mit anderen Worten: in einer Reihe von Fällen konnten Dissonanze “frei”, ohne Berufung auf den konventionellen Vorgang benützt werden.

Meine Theorie gründet sich auf dem Satz von der Emanzipation der Dissonanz, das ist von der Gleichsetzung der Auffassbarkeit der Dissonanz mit der Auffassbarkeit der Konsonanz. Das Problem der Dissonanz ist demzufolge nicht eines der Aesthetik, der Schönheit, des Wohlklanges oder dgl., sondern eines der Auffassbarkeit. Ist die Verwendung der Konsonanzen ermöglicht durch die Ähnlichkeit, d.i. Verwandschaft der Oktaven, Quinten, Terzen und Sexten miteinander, so bringt die Emanzipation der Dissonanz ihr gleiche Rechte aus denselben Gründen: auch hier ist es nur die Frage die Aehnlichkeit, rep. Verwandtschaft der zusammenklingenden Töne zu erkennen.

An eine Grund-Antithese von Dur und Moll kann ich nicht glauben. Ich sehe in der Tatsache dass diese beiden Kirchentonarten”überlebt haben”, nichts anderes, als die Wirkung des Prinzips der Auslese, wonach die Tüchtigsten, die Tauglichsten siegen. In Dur und Moll ist alles enthalten–sogar das Phrygische als Progression IV-V in Moll–was in Kirchentonarten möglich war, deswegen haben sie diese überlebt; deswegen haben Dorisch, Phrygisch, Lydisch, Mixolydisch aussterben müssen–sie waren die Minder-Tauglichen.

Gewiss hat die Tonsprache damit einige ihrer Kontraste verloren. Das ist unvermeidlich bei jeder Höherentwicklung. Es bleiben genug andere–erprobte–Kontrastmöglichkeiten; und die schöpferische Phantasie findet zahllose neue: es ist ihre Pflicht.

Die alte Harmonie, die den Konsonanzen Dissonanzen kontrastierend gegenüberstellte, war mit ihren drei- bis vier-tönigen Akkorden ärmer als die neue die 5, 6, 7 etc Töne auf zahllose Arten kombinieren kann. Ist der Kontrast zwischen einer viertönigen Harmonie zu einer 6-tönigen nicht gross genug?

Ich weiss, wie gesagt, dass solche Theorien meinem Werk nicht helfen, mir aber sehr schaden. Ich bin ein Mathematiker, ein Ingenieur, mir fehlt Unmittelbarkeit, Empfindung, Ausdruck etc. etc. *Allright, trotzdem bin ich nicht geneigt den Trottel zu spielen, als den mich viele gerne sehn möchten. So wie ich von jemandem einmal gesagt habe, der behauptet hat er sei “als Meister vom Himmel gefallen” (Josef Hauer!!), “Ja, aber auf den Kopf”. Ihm wäre es recht gewesen, wenn man nur sein Genie gelten liesse.

Nun habe ich sie genügend belästigt–ich hoffe, nicht zu sehr und zu lang.

Ich bin, mit hochachtungsvollen Grüssen, herzlichst,

Ihr

Thank you for this, which I found very interesting, to the degree I could follow — I’m no musicologist.

My own particular interest is in K’s letters to S, which at least one biographer indicates were written over a period of time.

EWK is much too young to have corresponded with AS. And his father Julius was too conservative. So I don’t think that any further direct correspondence exists.

EWK was born in 1897; what do you mean “much too young to have corresponded”? They met up as fellow exiles in LA in 1935 “”and soon became good friends” (“EWK”, Duchen 1996)

It seems that an account of what I’m seeking is to found in Brendan Carroll’s 1997 bio “The Last Prodigy: A Biography of Erich Wolfgang Korngold” (464pp), currently the hegemonic biography. A reviewer (on AZ) says:

“Korngold never forgot that the cerebral element in music could never take the place of the emotional. For example, his friendly but deadly serious battles over atonality and serial compositions with Arnold Schoenberg are key to understanding Korngold’s philosophy of composition and are well treated in Carroll’s book.”

I assume these are in written form, or mainly so.

(I think I recall that a revised & expanded edition is out this year, but I can’t find any evidence of it.).

A fascinating letter, and an important document showing Schoenberg’s thinking. There is the historicist view upon music history: the developments in music history are seen as developing from simple (‘lower’) to more complex (‘higher’), a view which stems from biology and science. In reality, sometimes a musical language developed from complex to simple (16C polyphony to 17C monody: the Florentine Camerata, Monteverdi’s Seconda Prattica; the transition from complex baroque towards simple Empfindsamkeit and Viennese classicism in the 18th century). According to S, elements which ‘survived’ did so because they were ‘stronger’: a darwinian vision, entirely inappropriate in the arts.

Then S explains that his understanding of dissonance is historicist as well: in earlier (medieval) times, people found thirds and sixths dissonant, and later they were ’emancipated’ to consonances. After a period of getting used to what is experienced as dissonances, they turn into consonances. Of course acculturation is an important factor. But ‘a dissonant’ is not a thing that can be emancipated, since it acquires its musical meaning only within a stylistic context: what works as a dissonance in one style, can be experienced as a colouring in another. We still hear dissonances in Bach as dissonances, otherwise that music would be entirely incomprehensible; but the same tone combinations in Debussy work not as dissonances but as colourings. Schoenberg saw ‘dissonance’ as a scientific, materialistic ‘thing’ instead of a relationship and that explains his idea that in the end, one could simply cancel dissonance and treat every tone combination as a consonance.

Roger Scruton in his Musical Aesthetics (OUP 1997) explains these difficulties exhaustively and definitely.

Julius Korngold – father of Erich Korngold – was the most important music critic in early 20C Vienna, and not simply a ‘narrow-minded conservative’. He championed Mahler’s music at a time when Mahler was considered a dangerous modernist. Nonetheless, Korngold represented the classicist attitude in Vienna, fruit of 19C Bildungsbuergertum, the educated bourgeois classes, for whom culture and classicism were symbols of civilization and cohesion. His critique of Schoenberg was motivated by his sense that such developments would, in the end, destroy classical music as it flourished at the time.

The mythology around Schoenberg and his two pupils as the heroes of progress used a simplistic accusation of ‘conservatism’ of early 20C Viennese music life to create an aureole over the martyr’s head, and that was a defense reaction. People were anxious at the time that their precious musical tradition would go under, as the political context soon was to sink suddenly and with dramatic consequences.

Meanwhile the Viennese three – with Mahler thrown-in as a John the Baptist – have become established orthodoxy with its own, appropriately nonsensical monument:

http://subterraneanreview.blogspot.nl/2015/11/a-monument-for-early-modernists.html