Can I still play the old Curtis way?

mainFrom our diarist, Anthea Kreston:

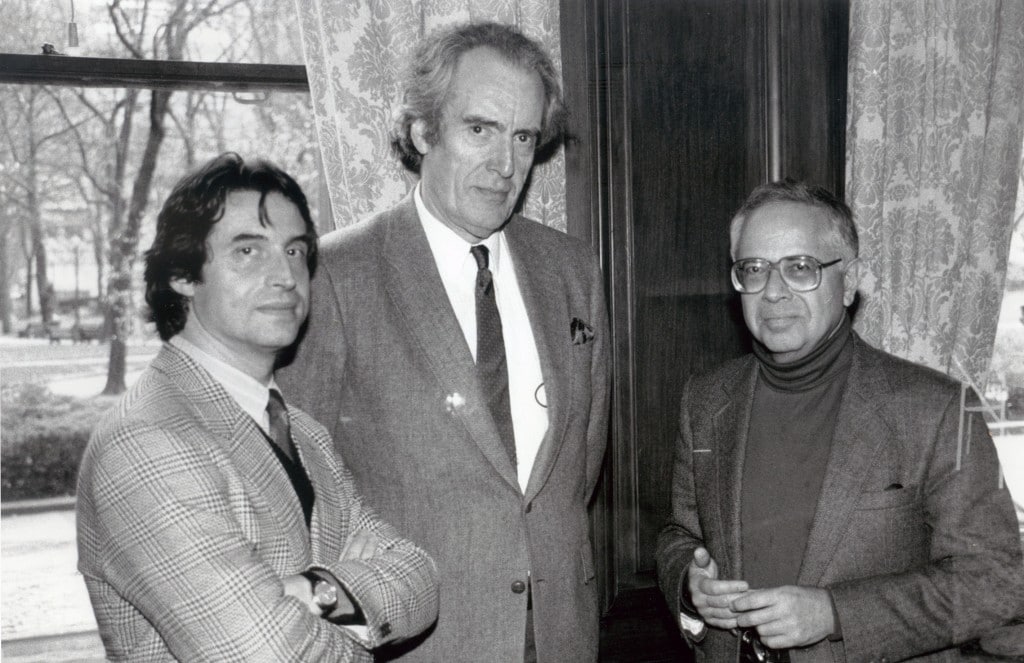

I am awash in memories, after spending a glorious and hard-working Brahms week with my piano trio and guest violist Roberto Díaz, President and CEO of Curtis. I went straight from my early morning train from a Quartet concert in Frankfurt to a long Trio rehearsal at the Universität der Künste. It feels like ages since we have really dug in together, and yet, a mixture of my new musical life in Europe found a balance with the traditions of my rigorous, romantic training.

Sitting down with Roberto Diaz was both an absolute pleasure, and a reminder of how I have changed – the depth of his sound (and of our pianists’ sound), the flexibility of phrase, the unapologetic, thick sound, the width of vibrato and crazy-seeming bow techniques. These brought me back to my fundamental training in music – the Curtis Sound (the Philadelphia Sound?).

The hours under the baton of Otto Werner Müller, our conductor and teacher – his relentless training if us all – the strictness of the length of notes (so much more sustained and with a length which is non-negotiable), the meaning of a dot over a note (refers to only that note, no preparing for the dot with the note before) distinguishing so clearly between composers – no bleeding between styles, each composer with a rigid yet full-throated and singing universe. Müller (whose hometown, Bensheim, Germany, I recently performed in), was a consummate trainer of both his conducting students and all players at Curtis, whose student body is exactly the size of a symphony orchestra. For example, there is one Tuba position, therefore only one opening every 4 years (17% of principal players in the top 25 US orchestras are Curtis graduates). Müller was demanding, honest, life-changing. He prized score-study above all else (there was nothing more insulting to an orchestra than to have a conductor step in front of them unprepared). He diligently edited all parts for the orchestra – remarking rests to be logically partitioned, adding his own rehearsal letters, bowings, clarifying articulations and answering questions in advance – anything that would streamline rehearsals. Every Saturday I had an additional 3 hours of “lab orchestra” as a part of my student work-study – those hours have influenced every part of my musical philosophy.

Roberto’s length of notes were so absolute – something I have veered away from because I was sounding inappropriately long and romantic here. After our first reading, I raised my arms in a “whoop-whoop” – and said “I am so all-in on these long quarter notes!”. Roberto looked at me, and said “oh, you mean not clipped?”. Exactly. There is only one length, and if you would like to go shorter or longer, you have to negotiate terms – but the fundamental rules form a firm communal sound – it is so easy to play together, even though three of us went to Curtis at different times.

Before the second movement of the Op. 25 Brahms Piano Quartet, Roberto said to me – “well, either you can tell me your bowings, or I can tell you mine”. The opening violin/viola duo has many options, and no clear choice. I have so many different ones crossed out, multiple ups written over multiple downs. It is a mess. I said, “let’s not talk – I have a feeling we will have the same bowings”, and low-and-behold, for the entire Quartet, we rarely were at odds. After the reading, he said “well, I guess we got the same free education”. The only differences – I sometimes would choose huge areas of all up bows, and he chose all downs. In the concert, we spontaneously did the first time all ups, then did all downs on the repeat. It was a fun time to have that kind of spontaneity and flexibility in a performance.

By this time next week, I will have played in Princeton and Library of Congress, staying with the widow of Isaac Stern and Andrew Moravcsik and Anne-Marie Slaughter. I have opted out of many of the hotels this time, preferring to stay with family and friends, to avoid the loneliness I experienced during my last US tour. Friends meet me along the way, with Trader Joe’s Trail Mix, – I am maxed out on all of my comps – hoping for a balance of fun, great music-making, and connecting with old and new friends.

Comments