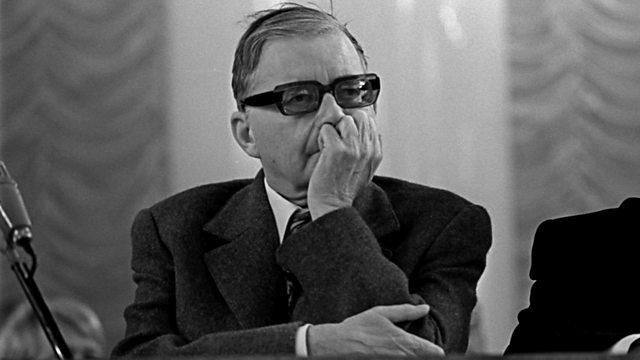

The virtuoso who just gave away his best violins

mainTully Potter has written a nice piece about Henryk Szeryng’s appetite for owning some of the most cherished violins, and his habit of just giving them away.

Szeryng’s Stradivari was the 1734 ‘Hercules’, once owned by Eugène Ysaÿe but stolen from the Green Room at the Imperial Theatre in St Petersburg in 1908, while Ysaÿe was on stage playing his Guarneri. In 1925, having surfaced in a Parisian dealer’s shop, the Strad was acquired for the Alsatian violinist Carl Münch, then concertmaster at the Leipzig Gewandhaus and later famous as the conductor Charles Munch, by his wife. Szeryng originally borrowed the ‘Hercules’ from Munch for some performances of the Schumann Concerto and bought it from him in January 1962 for $40,000.

Gary Graffman, who appeared several times with Szeryng at the Library of Congress in Washington, recalled: ‘He travelled with two violins, a Strad and a del Gesù, and my wife had to sit backstage cradling whichever one he wasn’t using.’ …

To his pupil and protégé Shlomo Mintz, Szeryng gave a fine old French fiddle by Jean-François Aldric, of which he said that it was ‘quite extraordinary’ and Mintz had often been asked if it was a Strad. To his student and teaching assistant in Mexico, Ecuadorean-born Enrique Espín Yepez, a professor at the National Conservatory, he gave his 1801 violin by the Cremona maker Giovanni Battista Ceruti. …

Read on here.

Comments