On London conductors – the great, the bad and the ugly

mainThe international clarinettist Murray Khouri, a player in the golden age of London orchestras, has written a memoir about some maestros he admired and others he endured. Read on….

Sitting in the Hot Seat (or Keeping Your Cool)

by Murray Khouri

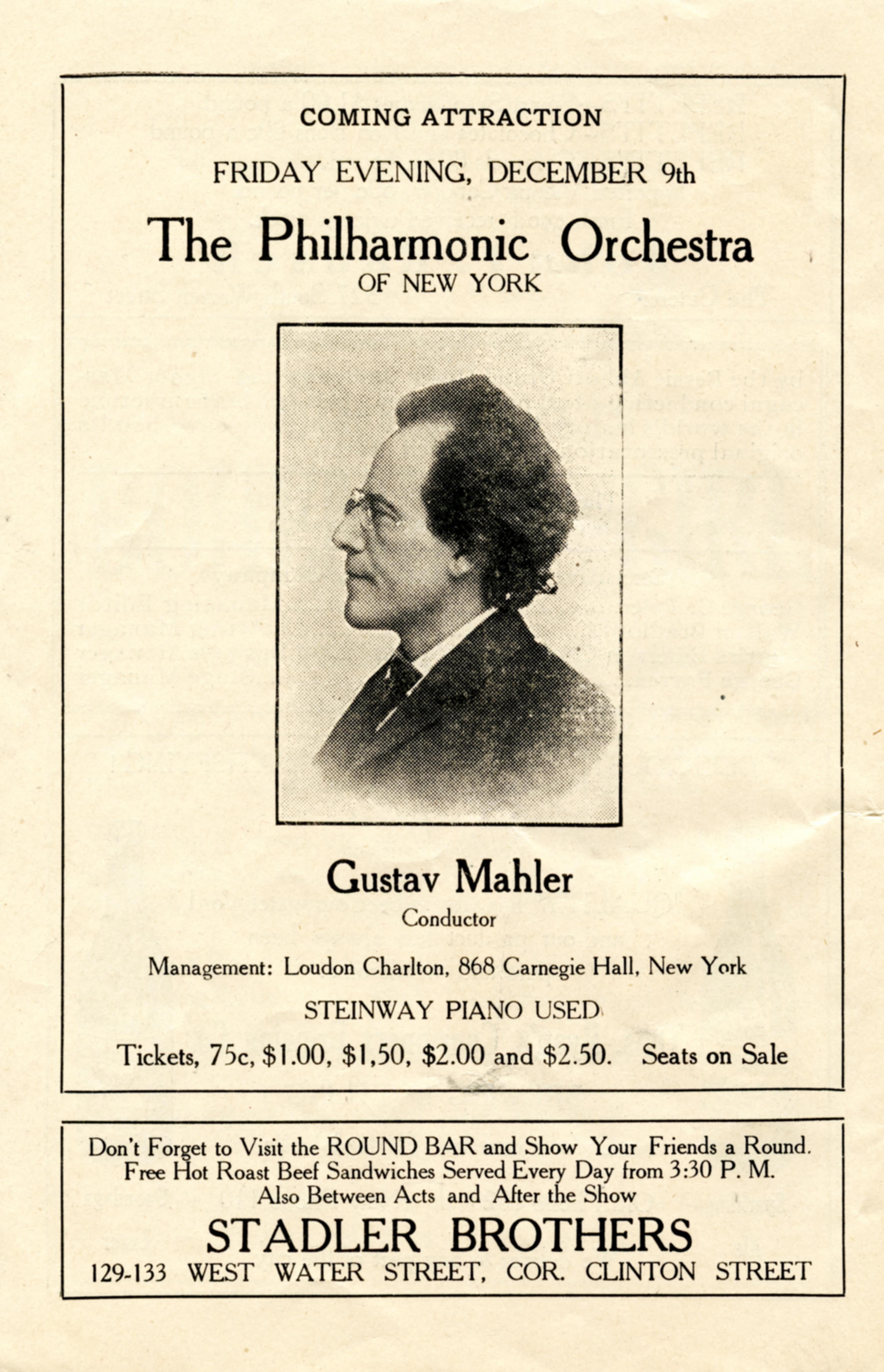

It’s a cold march morning in London. But in the Royal Festival Hall there is a welcoming warmth and on the stage the London Philharmonic Orchestra (“LPO”) is assembling at full strength ready to rehearse Gustav Mahler’s gigantic 6 th Symphony under legendary conductor George Szell. With tuning completed, Bernard Haitink, the music director, appears with Szell to introduce him and wish him well. Szell replies by saying “I last conducted this orchestra in 1937 and I don’t see any familiar faces,” looking at at least a dozen players who had played under him at that time.

“I want to play this symphony right through and I trust that there won’t be any technical errors”. With these chilling words ringing in our ears, the rehearsal began. True to his word, we played the 80 minute work from beginning to end under his stern piercing gaze, yet never a word spoken. Four rehearsals had been scheduled, a great many at this time. My feeling was that the LPO was currently a better orchestra than he expected, hence the absence of withering criticism. The day before the concert, he stopped, pointing to our first trumpet Gordon Webb. Was he really going to have a go at Gordon Webb? “Mr Webb”, said Szell, “you are the best trumpet player I know of”. The concert was predictably disappointing. An exhausted orchestra was driven hard at the morning rehearsal on the day of the concert, leaving nothing for the evening. Szell made two conducting errors in the Scherzo movement, but had the good grace to jab a finger into his chest, acknowledging that it was his doing.

Compare the above with the universally admired Rudolf Kempe, a favourite with most players, including myself. My first encounter with him was at a Beethoven concert with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. At the start he seemed curiously detached, simply looking at the tricky moments and at the tempo transitions and concerning himself with balance in the difficult dry acoustic of the Royal Festival Hall. I felt disappointed that there seemed so few insights. How wrong could I have been? The Eroica Symphony that evening was a performance I will never forget. He was a master of psychology, able to unleash all the orchestra’s pent up energy when it really mattered, that is, in the performance. Szell had the kind of technique that demanded absolute precision on the down beat, producing great precision at the expense of warmth of sound, whereas Kempe seemed to beat so little, using the warmth of his demenour and eye contact to produce a superb result. He also had a sense of humour, a quality absent with Szell. Kempe seemed to hear the orchestra from within, never playing “on the ensemble”. After all, he had been a Principal Oboe in Germany before taking up conducting. For me this was the summit of the conductor’s art, in fact, “art concealing art”.

Hungary must have produced more conductors than any other country that I know of. I was looking forward intensely to my first encounter with Georg Solti, having been brought up on his countless Decca recordings. With him, as with Szell, the orchestra was kept in the tightest grip with orchestral soloists bound hand and foot to his baton. It was his constant pressing and aggression that led to Solti as a conductor finally losing me. We were rehearsing Bruckner’s 8 th Symphony, a glorious work with its vast cathedral like sounds. To the brass section, “smash it, smash it”, he exhorted, producing a predictably raucous result. He simply couldn’t let the orchestra breathe and relax when the music called for it. Both Solti and Szell were pianists, whereas Kempe had been a Principal Oboe. They played on the orchestra like a keyboard, exactly the opposite of Beecham or Boult. ‘Elegance’ was a word absent from Solti’s vocabulary. Many, like me, found his baton technique wanting. All the time exhorting the strings to press harder, the opposite of Leopold Stokowski, with his penchant for ‘free bowing’. When we played the Mahler Symphonies with Solti, I felt physically sick at the unrelenting driving force, with one climax piled on after the other, until one was exhausted at the lack of repose.

It is probably a good moment to introduce that old magician into this account. Leopold Stokowski came to conduct the Royal College of Music (“RCM”) Symphony Orchestra when I was a student there. I could not believe he really was there, this living legend, famous because of his work with the Philadelphia Orchestra and the star of Disney’s Fantasia. We crowded around him, successfully getting his autograph which I treasure to this day. Then we started to rehearse Brahms’s Second Symphony. He stopped twice: the first time, to say to our First Horn, ‘Bravo, First Horn, that is a real waldhorn sound’. Then he turned to me, when I had a clarinet solo, to say ‘See frescoes around the Concert Hall? Your solos must stand out like that, in high relief’. And miracles of miracles, it wasn’t long before the RCM Symphony Orchestra took on the Stokowski sound. He was absolutely hypnotic, saying all the times to the String Section: “Free bowing, free bowing!”. All of which leads to answering the question: “What does it take to be a great conductor?” At its best, it is drawing the sound out of the players, the score in his head, not the head in his score. He didn’t beat time in the literal sense, rather, getting all the players to take responsibility for the end result, with him standing there, moulding and shaping the music. Another way of putting it is the ‘man on the podium is the conduit to the composer’s wishes, all the sounds passing through the one man’. There are of course many takes of Stokowski’s mannerisms: his affair with Greta Garbo and his curiously accented English pronunciation. After all, he grew up in London, going to America in his early 20s. And, driving past Big Ben in the Houses of Parliament, he drawled: ‘What name, big clock?’

Although they were quite different personalities, Sir Adrian Boult and Stokowski, in conducting technique, had many similarities. Boult’s relaxed fluid stick control was not rigid, giving the orchestra ample room to breathe. My first outing with Sir Adrian was in Elgar’s Second Symphony. There seemed to be no help from the podium, with everyone left to fend for themselves. I was quickly cautioned, “Don’t look”, and once I just sat there and played, all was well. In the many concerts I played with him, none were more memorable than with the Elgar works especially the Second Symphony. His knowledge and advice were truly inspirational. ‘Take out the bar lines’ and ‘swing it’ were popular phrases. During the 1950s and 1960s he was the LPO’s music director and he had his detractors. A story related to me concerns a visit to Russia in the early 1960s. In the grand hall of the Moscow conservatory, playing a Tchaikovsky Symphony, he was heard to say, ‘Change gear here. Double the clutch now and then slam on the dust bin lid’. I can’t imagine what the Russians thought of that. He rode the wave of the British musical renaissance giving great performances of Vaughan Williams’ Holst, Elgar, Stanford, Parry and many others. His seemingly impassive exterior concealed a bad temper and great depth of feeling. He stood tall and erect on the podium, feet firmly in one place. Not for him Leonard Bernstein’s dancing all over the place.

Of all the regular conductors there remains Bernard Haitink. I played in his first ever English concert, a performance of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony and found him sober and dull. How wrong I was. His gradual development bore rich fruit. He was exactly at opposite poles to Solti and his cycles of Mahler and Bruckner were, in my opinion, the best. His signature work was Mahler’s Third Symphony. Its primitive child-like elements were beautifully drawn and as the finale reached its climax, one saw him break down in tears. The magical off-stage post-horn solo arrived like a messenger from heaven. And just like Otto Klemperer, he had a rock solid ability to finish his symphony over a long span, ending the work without uncalled for tempo variation. He headed an enviable list of conductors appearing with the LPO: Karel Ancerl, Walter Susskind, Jean Martinon, Evgeny Svetlanov and Eugen Jochum, to list but a few. It was also a demonstration of Haitink’s generosity of spirit that he welcomed these distinguished colleagues.

I had become useful at the BBC both in sound and television and it was with the BBC Symphony Orchestra that I first came into contact with Pierre Boulez, quite an event. There seemed now to be two basic schools of conducting. One I will call “interventionist”, the other “non-interventionist”. Boulez had the most acute hearing of anyone in the business and at first he seemed to do very little other than beat time. We were playing Webern’s 6 Pieces for Large Orchestra (Op.6), when in the middle of one of the great climaxes, he stopped and said to the Third Trombone ‘You’re too sharp’.

And just to show he wasn’t a cold fish, at the climax of the dawn music of Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloe, he suddenly threw one arm across his chest in a moment of deep emotion. Playing some of the more chamber-like pieces such as Messiaen’s Oiseaux Exotiques and the Webern Songs, he required each instrumentalist to play his part alone before he would begin. He had made friends with Otto Klemperer and the two had much in common. There was a certain belief in the “neue sachlichkeit” (“new objectivity”), the opposite from conductors like Bruno Walter and Wilhelm Furtwangler. Boulez’s scores were models of pristine clarity making him the epitome of the composer/conductor.

Time to mention other conductors with whom I was associated from time to time. It is a long list, some names are illustrious, some less so. Antal Dorati did excellent work with both the London Symphony Orchestra and the London Philharmonic and together with Neville Mariner, is the most recorded of all London conductors. A pugnacious man who once caught a second violinist reading a book during a recording session, tried to flee the hall, only to find all the doors were locked. He was forced to sheepishly remount the podium and resume recording. Then there was Walter Susskind, complete with toupee, built-up shoes and facial make-up, but a conductor of vast experience very much at home with Czech music, the music of his homeland.

We saw a lot of John Pritchard, witty and urbane, who could be relied upon to do a professional job under all conditions. His visit to Australia was marred by a Sydney Opera House official who barred him entry to the building. ‘Never heard of you,’ was the remark. So Sir John Pritchard retired to a nearby restaurant and after frantic searching was finally found enjoying an elegant dinner. The performance finally took place almost an hour late. The Glyndebourne Opera took up much of his time, where he delivered polished performances of the Mozart operas.

I never had the opportunity of playing under Sir Malcolm Sergeant as he died soon after I entered the profession. He was heartily disliked by most orchestral players because of his patronising attitude towards the band. But he was capable of delivering outstanding performances of choral works, though in corrupt performing editions. One occasion he was greeted after a performance by a lady mayor who said, ‘Sir Malcolm, if I pluck your carnation, will your blush?’ To which he replied, ‘Madam, if I pull your chain, will you really flush?’. He showed great courage right the end, rising from his death bed to greet the BBC Promenaders one last time.

Then there was Raymond Leppard, whose tirades against the musical establishment resulted in his emigration to the United States. His performances of Monteverdi and Cavalli established new standards in this repertoire. Leonard Bernstein had visited London in the early 1950s to conduct the London Philharmonic Orchestra. He was deeply shocked by the drabness of the city and the working conditions of the musicians. Bernstein of course was a great composer/conductor, but for enjoyment, a tour with William Walton conducting his own works was unforgettable. He had no pretensions as a conductor but knew how his works should go with everything taken at a cracking pace. It remains in my memory, the opening of the violin concerto and the thrilling climax of Belshazzar’s Feast. Malcolm Arnold appeared from time to time and was hugely popular with everyone. His ebullient manner masked a very troubled man: in later years he was notoriously unreliable but works like “The Tam o’ Shanter Overture (Op. 51) and his Symphony No. 2 (Op. 40) have stuck in the repertoire as indeed they should.

I would like to sum up with some observations about the art of musical direction which we call conducting. The days of the tyrannical conductor have gone. There are no Fritz Reiners or George Szells to be found. And if it were not for Toscanini’s genius, orchestral players would not have tolerated his temper tantrums. The nature of orchestral players has changed. Both sexes are to be found, generally. There is also a better interaction between conductor and players. The Abbados and Rattles don’t have to raise their voice to get a superlative result. They signal a new era in the art of orchestral performance.

Murray Khouri

More, please!

Now that was interesting.

I always loved british musicians pragmatic and yet merciless and downright obectivity concerning orchestral life. London orchestras are a gold mine concerning not only anecdotes but the combo history and psychology in particular.

I would recommend Alexander Kok’s A Voice in the Dark, where he depicts a pretty

thorough and entertaining picture of London’s musical life, from the immediate post-war years until the 70’s. It mentions a wide range of typical orchestral-life issues, from the veneration and controversies towards “mythical conductors” through tea-breaks and sportcars (mainly Dennis Brain’s and Karajan’s common interest).

Beecham, Boult, Sargent, Toscanini, Cantelli, Karajan and Klemperer are each given very special mention – some of them even an own chapter, and legendarian luminaries such as Pablo Casals, Pierre Fournier, Arthur Schnabel, Dinu Lipatti, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf & Irmgard Seefried and many more are given vivid first-hand characterisations.

https://www.amazon.com/Voice-Dark-Philharmonia-Years/dp/0950620963

Great, illuminating article. Thank you

I like the idea of “playing on the orchestra like a keyboard.” That is, I don’t like it, but it’s a good description of what some conductors do.

One of our music directors gave a few conducting lessons to an orchestra musician, who passed along this bit of advice: you must move in such a way that, if you were playing an instrument, you would make a good sound on that instrument.

I don’t conduct, but having kept that advice in mind over several years, I appreciate it more and more: musicians, like anyone else, tend to mirror the body language they see in front of them. (Google “mirror neurons” for more information) A conductor with tight shoulders, stiff back, set jaw, etc., will trigger the same in the musicians. It can lead to a certain generic “energetic” quality in the music-making, but with a predictable lack of variation, as well as a common refrain of “I don’t know why, but playing for ______ makes my shoulders hurt.”

Very fascinating.

“Boulez’s scores were models of pristine clarity making him the epitome of the composer/conductor.” Aside from having a hands-on understanding of compositions, what else do they have in common? Furtwangler, Mitropoulos, Wand, Bernstein, Boulez, Sinopoli, Segerstam, Salonen: aren’t they vastly different?

His admiration goes to the very conductors I have always found mild and slightly dull.

Have listened to Kempe’s Brahms Requiem from the 50s and Lohengrin from the early 60s?

Maybe you are just a superficial listener, Stephen.

Surely he is wrong about Szell and Mahler’s 6th? He was due to conduct it just months before he died and had to cancel. He was replaced by Silvestri, conducting the 1st. Can anyone put me right on this?

Szell conducted the LPO in Mahler 6, and the Philharmonia in Mahler 4 at RFH in the same season in the late 1960s.

Yes, my programme collection shows the concert on 20th March 1969 with Janet Baker singing four of the Knaben Wunderhorn songs. Have to admit I don’t specifically remember how the concert went but I do recall Szell with the LSO playing Mozart 41 with such manicured precision that all the life got sucked out.

Kempe was a marvellous conductor to hear as was Klemperer until his very last years. Solti had more warmth than he’s often given credit for – he did a concert performance of Figaro which was relaxed and avoided pressing and I also remember a warm performance of Beethoven 4.

Very interesting! Wish more players would write memoirs. Too bad John Pritchard is so unknown these days. What few recordings I have are superb. Bernstein thought London drab? Well it was decades ago that he was there. Not today!

If you haven’t read it, Richard Adeney’s “flute” is very engagingly written.

JP was a friend and supporter of mine. I owe him a tremendous amount and miss him terribly. He was a consummate musician.

Well, to fair, London was pretty drab after the war and well into the 1950s and even later. It has really been only over the last 40 years that London has become exciting and vibrant.

Well said.

Perhaps the response was crafted by a ghost writer…

“The days of the tyrannical conductor have gone. There are no Fritz Reiners or George Szells to be found.”

How is a certain JvZ getting along with his new band?

And there is DB,of course…

He is not tyrannical, but exacting, and the players appreciate it and become more exacting than they were before, if possible. They feel they’re growing. That is how he can build-up an orchestra’s performance profile (like the Hong Kong Phil who is doing all the Wagner nowadays to great acclaim).

Maybe he learned something when JVS lost control over his ego in hiring a new principal musician. Dallas Symphony operates in a right to work state, unions aren’t as strong as say NYC. I did get unpleasant there when the musicians committee did not support is candidate. Both candidates were exceptional musicians. Involved story, but his made life miserable for members of the committee. Gent heading up the players side was an object of JVS anger. JVS would stop rehearsal to berate the fellow for messing up a section. Only problem individual in question was in the middle of a long rest. The DSO board stepped in to cool things off when the story hit the paper.

NY Phil is a different world. It will be interesting to watch.

Barry Tuckwell had a different view of Szell at the LPO. Tuckwell said that Szell expected the best of his players, but wasn’t Fritz Reiner. Tuckwell summed up his comments with “we kept hiring him.”

Did Tuckwell play with the LPO?

Yes – In 1955, he was appointed first horn with the London Symphony Orchestra.

During his 13 years with the LSO, which is a co-operative orchestra run entirely by the players, he was elected to the Board of Directors and was Chairman of the Board for six years. The chief conductors during this time were Josef Krips, Pierre Monteux, István Kertész and André Previn.

Don’t understand this. The LSO is not the LPO. Did Tuckwell play in the LPO or not?

I enjoy the vast majority of Szell’s recordings, especially those of pieces by German/Austrian/Czech/Hungarian composers. That said even Szell admitted that the CO often played their best at the dress rehearsal. I’ve never understood why he insisted on over rehearsing. In his autobiography Starker mentioned that after Szell’s first rehearsal with the CSO he felt compelled to tell him how much he enjoyed the experience but soon became annoyed by the constant repetition. I was hoping that Michael Charry’s Szell biography would have addressed why such a superb musician seemed incapable of operating harmoniously.

Reiner dominated his players by pulling a face as if he had just sniffed at a thermometer:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mlfWkSMVSt8

Reiner would right CSO principals repeating a passage over and over until they mad an error. He started in on the principal trumpet one morning. After a few runs of this, principal trumpet said, we’ve got twenty minutes until lunch. You can keep this up if you want, I’m not going to make a mistake.

I listened to some of the first movement and am still looking for character, joy and beauty. They must have been squeezed out, along with the mistakes.

Thanks. The best Slipped Disc post in ages !

And how about this bit ? 😉

==When we played the Mahler Symphonies with Solti, I felt physically sick at the unrelenting driving force,

A memoir along the same lines would be very welcome I’m sure.

In the LP box set of Mahler symphonies conducting by Bernstein, there was an extra LP of reminiscences by musicians who played for Mahler. (They were recorded by Bill Malloch.) It’s been years since I listened to it but as I recall it had some interesting comments in it.

Maybe the players didn’t have the stamina to keep up with Solti. After all, the CSO was/is a better orchestra. Solti was used to working with a much better orchestra than the LPO.

Solti went to Chicago after he’d been conducting in London for many years. He was older, more settled, more relaxed, more collegial. Reading descriptions of him by 1960s-era British musicians and watching him rehearse in Chicago many times in the early ’80s, one would think it was two entirely different conductors and personalities!

It was the LPO who named him “the Screaming Skull,” not Chicago…

I think all the disparaging nicknames started earlier than his tenure at the LPO at the Royal Opera Covent Garden. It was a mediocre band until he made it into a decent orchestra.

And in his autobiography, Solti admits most of these flaws in his 1960s London conducting, and regrets that he didn’t dial back the demands a bit…..and maybe take his foot off the gas once in a while.

My impression of him (grew up in the Chicago suburbs so I heard a LOT of Solti from ca. 1981 until his passing) was that while he sometimes got carried away and overheated the music, his demands on the players were driven by the heat of the moment. He wasn’t mean and vindictive like…..some conductors were back in the day (and a few still are >>cough!<>cough!<<).

I remember Solti doing the Beethoven Fifth a LOT in Chicago in the early 80s….and just not getting it right. (How can the guy who polished off the whole Ring cycle for Decca NOT get The Fifth?) Then finally ca. 1986 or so he threw out all the practices he'd accumulated, bought a clean copy of the score, re-learned it from the ground up, relaxed a bit and stopped applying Solti Hot Sauce to it….AND finally did an excellent LvB 5. At least in the later performances I heard….

Musicians who performed under Solti who may be reading this: Did you notice any "mellowing" in him in the 1970s and '80s??

Music making is not a sport and about who can play loudest or has the most “stamina”, Van.

Ha. That’s what you think.

RODNEY,

Are you the former leader of the LPO? Would love to hear from you.

Murray

I heard Solti’s performance with you of the Mahler 1st in about 1966. It was wonderful – and the orchestra applauded him at the end. I didn’t notice you were sitting on your hands!

I agree. Puts Slippery D up in my estimation. Some authoritative and wonderful memories. I hope more including Klemperer, Davis, Kubelik, Keliber, Kertesz, Maazel. The list could go on (and on)

Fascinating read!!!!

Having played in the New York Philharmonic for quite a few years, I am surprised that you put Boulez in the same category as Stokie, Szell, Lenny, etc. In my opinion, Boulez single-handedly destroyed the musicianship of the New York Philharmonic that Lenny, Bruno Walter, Toscanini, produced. Boulez was a time beater who may have had good ears, but except for the pieces he knew, didn’t elicit much music out of the orchestra. Different Strokes for different folks I guess.

PB wanted to delete the expressive/emotional dimension from the scores, and concentrate on their purely sonic qualities. There is something to be said for avoiding the over-romantic pathos and bombast, but PB went into the other extreme. He wanted to hear what is clearly and precisely written in the score, but that is not possible because there is much music between the notes which cannot be clearly notated and are dependent upon the conductor’s musical udnerstanding. I rest my case.

Yes, .et’s have more memoirs by orchestra platers. Just reading Anshel Brusilow’s “Shoot the Conductor.” It’s great.

Very interesting….. memoirs of orchestral players could be quite embarrassing for conductors, so the players should try to live very, very long.

Great memories. Thank you for sharing.

This was a fascinating look into these legendary musicians, presented in much the same way as the old Movietone newsreels did the news. Sort of a “soundbyte” moment of each remembrance, but revealing and salient in that brevity.

No comments on von Karajan?

Of UK orchestras he only conducted the Philharmonia, so the Kok memoirs would be the relevant read I guess.

A really insightful summary of those orchestral times, much of which I was in the audience, goggle eyed. I wouldn’t argue with any of MK’s opinions in his piece, but he’s hard on Solti, whose time at Covent Garden was full of wonders, Rosenkavalier, Arabella, the Ring and so much more, and his recordings, helped by a great team at Decca were groundbreaking. Also Klemperer, who conducted all the Beethoven symphonies sitting in a chair wavIng his arms ineffectually in front of him, no beat In sight, but the rock solid rhythm and huge sonority wS mind-blowing. The Philharmonia musicians knew exactly what he wanted.

The three conductors whom I most admired and held in great affection were Sir Alex Gibson, Claudio Abbado and Bernard Haitink. They all were more concerned with the music than their own image and were respectful of and loved by the players. I could give examples of each one’s gentlemanly behaviour,but one really stands out. During a break in Fidelio rehearsals at Glyndebourne a group of us were queuing with Haitink in the old courtyard cafe when the leader came up to Haitink,. “Bernard ,Nicholas is so upset at cracking in Abscheulicher that he is almost ready to resign.” Haitink asked for him to be brought to him. A couple of minutes later the obviously distraught horn player arrived and Bernard took him aside,but we could hear the exchange that followed. “Nicholas,how long was I principal conductor of this orchestra?””Twelve years” “How many years have you been playing first horn for me at Glyndebourne?” “Twelve years” ‘Now do not realize Nicholas that I would not have had you as my First Horn for 14 years if I did not think you were the best horn player available?” Silence. “I think you are the best horn player in Europe and you can crack in that aria every performance and it will not change my opinion: You are the best horn player in Europe,!” The horn player then burst into tears , at which point Haitink put his arm around the man’s shoulders and lead him off for a stroll in the garden. No wonder the orchestra were so fond of him. I can imagine the reaction of some other conductors to such a problem. Of course the player never cracked in the aria again.

I imagine the horn player was Nicholas Busch (spelling?) Yes, a truly great horn player. I’ve been listening to Haitink all my life and share your enthusiasm. Every time he comes to Paris, it is a a real event for musicians and audiences alike.

Haitink has become one of my favorite conductors. With Skrowaczewski no longer with us and opinions divided over Muti, Haitink may well be the genuine “last of the breed” of larger-than-life conductors.

I have to say, this story raises him even *higher* in my estimation. Great music rigor coupled with Dutch plain spokenness and real humanity. What a man!!

Early in my music journey Haitink had a prominent place (still one of the best Emperor Concerto recordings EVER with Arrau), then I kind of lost interest in him….and now as I get older and so does he, I’m enjoying his performances more and more.

I heard an interview of him a while back where he admitted that toward the end of his Concertgebouw music directorship, his interpretations got kind of stale. I wasn’t thrilled when he was announced for filling a sort of interim “music advisor” role at the Chicago Symphony between the Barenboim and Muti administrations, but it turned out to be the Golden Age of the post-Solti era. The CSO (and by extension, its audience) was so fortunate to have him!

Are you the singer

First of all, I’d like to thank the writer for his interesting summary of the conductorial styles of the various individuals referenced. I think it was an illuminating and interesting read. It confirmed what I knew to be true about several of the conductors mentioned, of whom I knew several as an adolescent.

With that said, I’d add that first impressions are often correct. That could not be more true than with Haitink. The writer’s first impressions were spot on. Yes, musicians love him, and he’s a literate, intelligent, perceptive man, but since the beginning of his career, he has been characteristically incapable of rendering a performance with his personal stamp interpretively. He conducts a summary of the notes, often gorgeously played by leading orchestras, but in my worthless opinion, his performances categorically fail to incandesce. There are many other conductors who are capable of remaining true to the score and composers’ intentions but manage to bring more character and illumination to their interpretations than Haitink ever has, notably Abbado, Kleiber and Jochum among others. Haitink is clearly the third most overrecorded conductor of all time after Karajan and Ormandy. The only place Haitink truly succeeds is due to his emasculative effect on massive, heavily orchestrated works, such as the symphonies of Shostakovitch and the Tone Poems of Richard Strauss, which pruned of their bombast, come up elegant and insightful. Pretty much everything else, in my mind, is characterless drivel. Sorry. But first impressions are right.

I always found Haitink a musician of admirable integrity and modesty, not wanting to impose his ‘ego’ on the score, but trying to render it as faithfully as possible and within the boundaries of good taste (where people like Mahler and Strauss often spill over them). You could call him a ‘classicist’: choosing the moderate, the elegant, the pure, the sophisticated and polished. That is why his performances often have the atmosphere of an English tea afternoon party and this may explain his popularity in the UK.

It is late, and, having dined, I am not at my sharpest. But I shall pick up a lance in BH’s defence.

The fact that Haitink does not try to impress his own ‘interpretative stamp’ on the works he conducts is, I think, exactly why some of us so prize him. Many music lovers, after all, go to concerts in order to listen to the works on the advertised programme — not to hear those works as ‘stamped’ by Maestro X. (Why is ‘stamping’ thought to be a good thing?) For my part, I can only report that this modest approach has often led to performances which live long in the memory precisely because of their lack of egotism or eccentricity. E.g.:

a Mahler First (at the Barbican in January 1998, during BH’s first concerts with the LSO) which, for once, sounded like the music of a young composer rather than middle-aged bombast;

a *Don Quixote* with the BPO at the 2000 Proms which, for once. sounded like music;

a *Pastoral Symphony* with Chamber Orchestra of Europe at the Barbican in (??) 2016, where one had the wonderful illusion that the score was playing itself.

As the last example shows, Haitink is still able to produce performances at this level even in his late 80s. May he long keep going.

Willi~ Per my comments above, I do somewhat agree with you about Haitink’s work in the ’70s and ’80s. He did drift into blandness. Sad to say, I thought some of his most boring work ever was with the London Phil, though I’m going only by the recordings – never heard them in person. But once he got past the grind of being the ACO’s MD, I think he settled into a phase where he conducted less but put more into it. (But how can an outsider really say?)

I thought he and the Chicago Symphony were a superb combination: a steady hand on the tiller, which the orchestra needed at the time, while the orchestra seemed to electrify his conducting.

But one man’s “bland” conducting is another’s “doesn’t impose his personality on the music, etc.” Haitink’s more in the Monteux mold – his interpretations are not extremely individual and personal, but always highly musical.

And as somebody above said, *nobody* paces the final movement of Mahler 3 better than BH (evidence: CSO recording, Proms concert last year – or was it 2016?).

You have not heard truly lobotomizing and boring performances than BH leading the BSO during the period between Ozawa and JL. After one especially brutal Brahms 1st, at the beginning of the next performance, the principal tympanist Vic Firth seemed to be willing BH to invest some vitality with especially urgent playing. After the first 30 seconds the performance bogged down in the typical BH snooze. I was surprised to read the earlier comment about Reiner trying to induce principal trumpet Herseth into a mistake through repetition. My understanding was that AH was one of the few musicians FR genuinely admired. A more typical FR story is the glowing recommendation he wrote for a CSO violinist applying for a position with Szell in Cleveland. The audition went well, Szell hired him and thanked Reiner. At the first live performance Szell realized the violinist suffered from paralyzing stage freight and that he’d been duped.

Actually, I believe you about a Haitink snoozefest with the BSO. As I said, he had a looooonnng boring phase that he didn’t really shake until….well, I discovered he’d broken it during his CSO “advisorship”. And let’s face it, the Ozawa-Era BSO had its own problems extending into the post-Ozawa Era – some folks say it persisted through the Levine Era.

Reiner doggin’ Bud Herseth: Yep, sounds like Reiner. He liked to push players to see if they’d break. If they did, it was “You are the Weakest Link. Good-bye.” But if they stood their ground and were good musicians, he’d respect them. Did the same thing to Ray Still, who was a pushover for nobody, and same deal: Still passed the “test” and was OK in Reiner’s eyes.

Reiner unloading a problem player on Szell: Ha, good story. Too good, actually. So good, I suspect it’s Urban Folklore. But who knows?

I one of my earlier careers Reiner’s actions would get him labeled a “Toxic Leader.”

The end of the Reiner-Szell story was supposedly Szell telling Reiner that he wrote an equally glowing recommendation for the violinist prior to an audition with the Met orchestra of the 50’s. Supposedly Szell indicated that his aversion to audiences wouldn’t be an issue due to poor attendence!

Some interesting anecdotes about LPO, LSO, Solti, Haitink and many more here.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Special-Timpanist-Alan-Cumberland/dp/1541383508

Nice article Murray, great insights. R.I.P.

AL