‘I would work for half my pay if I thought quality would be defended’

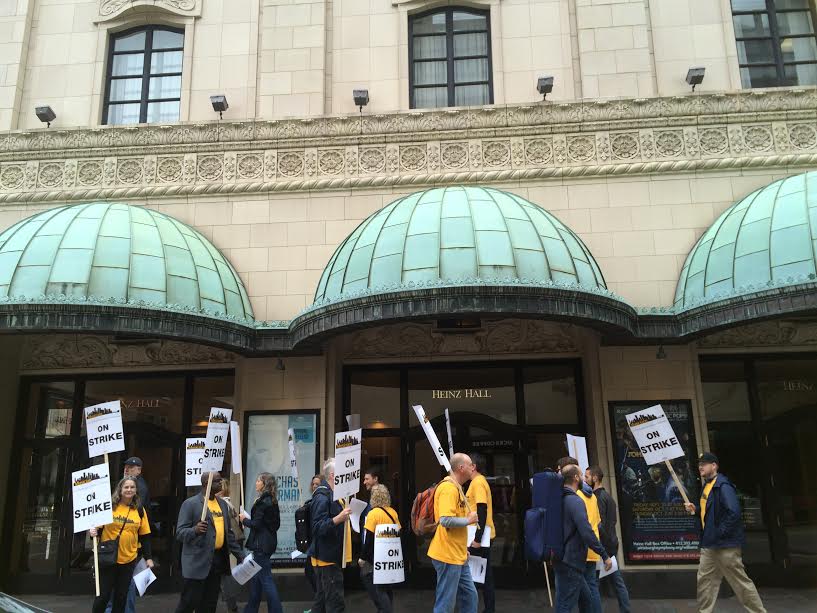

mainOur Berlin-based diarist Anthea Kreston, catching up with an old friend in the Pittsburgh Symphony, finds the mood fragile and fearful after the bitter and unnecessary lockout.

I am sitting, eating another glorious breakfast at my hotel in Waterloo, Brussels. Today is my final day of three here – this afternoon I catch a plane back to Berlin just in time to have a late evening jump-start with quartet on the Schumann Piano quintet.

The Queen Elizabeth Music Chapel is a wonderful place to reconnect to my own youth as a student – I rekindle and share my experiences as an eager student with the Guarneri, Emerson, Cleveland Quartet, Felix Galimir, Ida Kavafian, Isaac Stern, and all of the others who so deeply influenced me, challenged me, and encouraged me to always open my heart and ask more of myself. To never be satisfied, but to forgive myself at the same time. The students here are so warm and open – quick as can be, and it is a true gift to be able to teach here. I worked with the wonderful Arod and Girard Quartets this week, and equally incredible Busch and Zadig Trios.

I am thankful for many things – and at the same time, I am in contact with old friends who are struggling with their own lives as members of orchestras who are stumbling back from lockouts. As I exchanged emails with old friends this week, a voice from within the Pittsburg Symphony touched me deeply. It is a voice of a wonderful musician – someone whose soul speaks through their playing – a generous person, a person who has been an inspiration to me consistently since we met as teenagers. I think these words should be shared. This person has allowed me to include their words, anonymously.

‘Every musician who has been caught in a lockout has to consider their future quickly – most have families, children in school, people who rely on their income. They scramble to find other work, begin taking auditions for other orchestras, a gruelling process – especially when it is unexpected.

‘I think it is important that the general public knows how devastating a strike can be personally for musicians. We are hurting, and ours was far shorter than Minnesota’s! In fact, during our strike, the idea that it could go on as long as theirs, loomed over us day after day…making it that much more scary. I find myself having to use more and more self help tips on being positive and just getting out of bed at all is sometimes a struggle.

‘The PSO is back at work, but an innocence is lost. It is no longer that place that we’ve always had that sustains us, it is a weird feeling of distrust and looking out for ones own future, because no guarantee of anything really improving. The audiences have been incredibly great, the community is amazingly supportive, which is great but further highlights the injustice of having been dragged through this nightmare of a strike because of the lack of proper management by our board mainly, who we all thought were doing their job.

‘There are people on our board who honestly believe that classical music is a thing of the past, no longer relevant and others who think we’d be better off as a smaller band. Knowing that just eats at me and I think that is what has hurt us all more than anything! I would work for half of my current pay if it meant that the quality was going to be defended tooth and nail, if our pay was going to procure the best soloists, or for us to play more Mahler or commissioned works, for example. Take my pay, and cut the many video game and backup band type concerts we’ve played more of recently in order to “make money”. Those are so degrading.

‘I think my main desire of having (I will insert here that this person began to take auditions again) another job was just to finally say goodbye to the filth of all that bad music and to dedicate my full time to quality, opera music especially, which I’m dying to play. They work really hard? Great! Count me in! I can still play hours and hours a day no problem when I love the music making.

Oh Anthea, I’ve gone on today, a low one. Thanks for reading, “listening”.;).’

Every person tells a different story – has a different path through the complicated life of a classical musician. No path is easy – all require sacrifices for the player and their family – and challenge our innate need to do the fundamental, important work that we were trained for, and that we fell in love with, many of us, before we could even read or write. We hold onto that love, and it will always come back to us – one way or another.

This Pittsburgh musician is going to have a difficult future because it is normal practice for USA orchestras to play video game music, movie music, music with hip-hop artists, music with rock artists, pops concerts, educational concerts etc. Looking through the Baltimore or Washington symphony concert programs these efforts are also a significant chunk of the orchestra’s responsibilities.

There’s a financial reason to do this, but there’s also demographic reasons, as Mahler and mainstream opera are (presumably) performed in front of old, white audiences. (I myself have seen the difference in the audience when Marsalis, rather than Mahler, is performed). I suspect that younger classical musicians are less likely to find concerts outside the canon to be “degrading” and “bad”. They may be pleased to have a wider audience with respect to age, ethnicity and level of musical education.

Also if one seeks government or community support for orchestras – this falls in the USA to the political center (well maybe not anymore) or left. Based on some knowledge of the grants process, the broadness of the demographic groups likely to benefit from an arts effort plays an important role in receiving government support.

On the other hand, there are folks (like Philip Kennicott here in DC) that have said that taking the orchestra away from performances of the canon or challenging new works takes it away from what it does best. He argues this effectively in this article

https://newrepublic.com/article/114221/orchestras-crisis-outreach-ruining-them)

I am sure that there are musicians such as the Pittsburgh musician quoted here that are discouraged by these other ventures. But I run into young musicians that are very pleased to play video game, movie music or hip-hop as part of their music career. If they only played in front of a select audience, they would definitely feel something missing.

I lean on the side of the traditional role for orchestras, but I think that I and the Pittsburgh musician are swimming against the tide here.

That article by Kennicott is a strong one. The predicaments it describres are also appearing in Europe, but less so, its musical tradition more resistant. But it is the same problem.

Quote:

“Americans tend to draw the line between connoisseurship and fatuousness at a level just slightly higher than their own degree of appreciation.”

I feel for your PSO colleague. That is a hard place to be in. It’s like when a relationship goes bad: it can damage your faith, not only in your own ability to even have a good relationship, but whether good relationships are even possible.

We like stories of resilient people who pick themselves up and dust themselves off and continue undeterred on their chosen path, apparently no worse for wear. The truth is, not everybody finds it easy to “just move on.” I hope this person can.

I am disheartened by the statement that members of the board believe that classical music “is a thing of the past, no longer relevant…”

These sorts of statement make me wonder why those person are on the board if they believe as they do.

It’s far from the only symphony board where that is the case.

The burning subject of relevance of symphony orchestras, and of classical music in general, is the central concern of the Future Symphony Institute in Baltimore. A recent essay on their website is by British philosopher and musicologist Sir Roger Scruton:

http://www.futuresymphony.org/the-virtue-of-irrelevance/

There is more to come.

Im with David’s comment on the Board. Im glad that musicians such as your friend dont want ‘dumbed down’ orchestras – play some of the lighter stuff that puts bums on seats, yes, but classical music is far from dead. Lets hear the Mahler. On another note, the line that really spoke to me personally was “To never be satisfied, but to forgive myself at the same time”. That can be a fine balance – its good to be reminded of it!

Minnesota was LOCKED OUT, not striking. There is a big difference.

I notice that Anthea’s friend, whether she means to do so or not, is blurring the distinction between a strike and a lockout. She’s basically using the two as synonyms.

(Yeah, I think the friend is a woman, for whatever that’s worth.)

I know that this was a communication between two musicians and not something for the public, but even so –

– one important thing we learned (if we were paying attention) from the experiences in Minnesota and Atlanta is that most of the public does not know (or, at least, does not process) the difference between a lockout a a strike.

That fact is a serious problem in terms of keeping the public on musicians’ side, and musicians badly need the public’s support.

And I think we need to keep the distinction clear in our own minds if we’re to have any hope of getting the public to understand it. Blurring the distinction just is not helpful.

– – – – –

(Come to think of it, I suppose that, for musicians who are striking, it is helpful to blur the distinction between a strike and a lockout – in a narrow, self-interested sense. And that’s all I’ll say about that.)

So yeah. A contract negotiation stalls, and neither side will budge from whatever position they’ve arrived at. The usual “last best offer” language is duly used, and nothing happens. At this point, one side or the other may throw up their hands and say “OK, fine. We’re done with talking.”

If management initiates the work stoppage, it’s a lockout: the basic message is “you can’t come back to work unless you agree to our terms.” If labor initiates the work stoppage, it’s a strike: the message in that case is “we won’t come back to work unless you agree to our terms.” Hopefully, negotiations continue in either case.

That said, the situation can change. Once the musicians go on strike, the management can say (I’m paraphrasing, obviously): “You want to strike? Fine. We have no intention of changing our terms, and we will not let you back in until you agree to them.” Depending on factors like public opinion and the musicians’ ability to live without paychecks for an extended time, it can turn into a de facto lockout.

That’s what happened when my orchestra struck a few years ago. The musicians, for the most part, didn’t have the financial wherewithal to weather a long drought, so after 4 or 5 weeks when management offered a small (approx. $450/year) improvement over their previous “last best” offer, with the caveat that, if we didn’t accept, they would have to cancel two more months of the season, we said yes. So — our side initiated the strike, but the other side held all the power.

Not trying to justify anyone’s wrong use of words, just trying to introduce a more nuanced view of things.

Anthea’s friend is welcome and entitled to his/her own personal opinions about whether he/she would still be adequately compensated at 50% of his/her current salary, but I think it’s dangerous and insidious for musicians to take any part whatsoever in communicating to Boards and managements that all we really need is the psychic income from playing the Great Music That Is Its Own Reward. It’s not! Certainly not for anyone in the vast majority of professional orchestras in the US whose players are paid nowhere near a decent full-time salary and benefits. Careless statements like this resound throughout the country in contract negotiations for years, even decades.

At some point, American classical musicians must face reality: this is not our music.

We have our own classical music: jazz.

Trump is hastening this realization, he’s getting rid of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (PBS), the National Endowment for the Arts, the two primary nation-wide sources of European classical music in the US. We once bemoaned that only the New York Philharmonic and the Met are ever shown on PBS, but under Trump, NOTHING classical is going to be broadcasted nationwide.

Now, the public must depend on free streaming on the internet by American orchestras. But the internet provides so much competition, who’s going to tune into a live stream of the Detroit Symphony?

The future is bleak for European classical music in the US. For some people, like Trump and his America First, it’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Yeah! And let’s get rid of those irrelevant art museums. Too many dead white guy artists. And Shakespeare? OUT!!! And let’s not even talk about the printed word.

Now if Jazz is supposedly our classical music, I have news for you. The younger generation HATES it. So scratch jazz, too.

No.

Jazz is not America’s classical music.

Jazz is jazz.

American classical music is America’s classical music.

That would be, e.g., Copland; Bernstein and Gershwin (who wrote in other genres as well, of course); Reich; Glass; Harrison; the two John Adamses; Morton Lauridsen and Eric Whitacre; and two generations of younger composers, male and female. Not to mention, of course, Carter and Cage and America’s classical avant-garde. (Maybe I’m wrong, but I don’t think that John Cage could have happened in Europe.)

The two genres, jazz and American classical music, use similar instruments and roughly the same system of keys and harmony; other than that, they are utterly different. Comparable in terms of artistic achievement, but not at all alike.

(One could make an argument, for instance, that contemporary jazz has nearly as much in common with Indian classical music as with American classical music.)

I don’t think it does either genre – or us, the listeners – any good to conflate the two.