Worst job? Orchestral player. Best? String quartet

mainSome timely thoughts from our diarist, Anthea Kreston of the Artemis Quartet:

With the recent upheavals of the Pittsburgh Symphony and Philadelphia Orchestra, Norman Lebrecht asked me to address the differences between a life as a chamber and orchestral musician. So, here goes!

As a student at the Curtis Institute of Music, I was constantly rotating between being completely overwhelmed, inspired beyond my wildest dreams, dejected and convinced that I could never reach the level demanded of me, and soaring with a musical abandon never anticipated. In hallowed halls, which have historically and currently hold the legends of classical music (both as students and teachers), I shared Wednesday teas with students who already had enviable solo careers, management, and recording contracts. Teachers, most of whom had arrived from Europe in the 30’s and 40’s, were most often octogenarians with storied pasts, with incredible careers and direct links to the great composers and performers of Europe. Alumni are amongst the front ranks of soloists, conductors, chamber musicians and hold leading positions in top orchestras the world over.

It was here that I saw the vast career opportunities available to musicians, and as most of my friends joined top 10 orchestras immediately after leaving school, or simply continued their incredible solo successes, I was adrift with indecision. In search for a deeper meaning, my first quest post-Curtis was to buy my first car (a used Buick Skylark) and drive solo cross country to temporarily join a commune in Oregon and assist in the home birth of a dear friend from high school. From there, I moved to Oberlin to have a musical detox, finding a house (which was immediately condemned and destroyed after I left 6 months later) in which, to get from the bedroom to the kitchen, a person would have to take a running jump across a disturbingly sagging floor to cook their rice and beans.

All the while, old friends would be in contact – I would drive to visit them in their posh apartments and swanky homes – they had adult clothing and matching dishes – leased cars and international touring schedules. Although no one challenged me directly, they would ask my plans – why didn’t I audition for an orchestra? I didn’t know the answer, but I did know that orchestra wasn’t the answer.

I moved to Cleveland soon after, started a degree in Women’s Studies, and began to experiment with effects processors and foot pedals. Before long, I had a steady gig with a rock band, and I considered the evening a raging success if I left the bar we were performing in not drenched in beer.

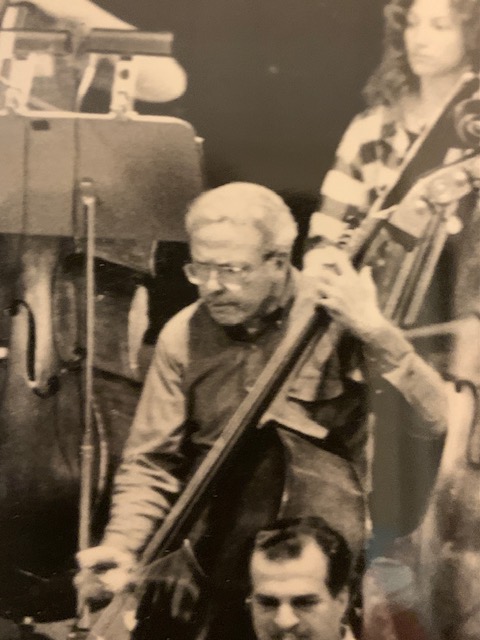

One day, my “a” string broke, and I decided to go to the Cleveland Institute of Music and see if they had a music supply store. As I wandered the halls, a tentative voice said “Sarah? Sarah Kreston?”. This was before I changed my name to Anthea. The voice belonged to Nicole Johnson, an incredible cellist I grew up with, and daughter of the esteemed cellist and teacher Mark Johnson of the Vermeer Quartet. She could barely recognize me – in my outsized black army boots, red kilt, white t-shirt with a hand-lettered political statement, and a nearly shaved head, she had to do a double take.

She wondered what I was up to – no one knew I lived in town. She had a string quartet which was going to Norfolk for the summer and their violist just dropped out. Would I like to read with them? We exchanged numbers, and my obsession with chamber music began.

The first 10 years were difficult in every way, but I loved the challenge and didn’t mind being poor. As my focus eventually broadened to Piano Trio and university teaching, my financial portfolio grew. I had variety, stability, a beautiful farm house in Connecticut, a wonderful partner and friends.

It was during this time that the first break-downs of the American Orchestra machine began. First one orchestra and then the next folded, went on strike, took multiple pay-cuts. Suddenly the diversity of my life offered a financial stability which did not exist for orchestral musicians who were locked into a one-salary position.

In 1996, a landmark study was published by Harvard Psychology Professor Richard Hackman. It detailed his study of the most and least satisfying jobs in America. A surprise to most, but certainly not to me, was the placing of an orchestra musician low on the list, just after that of a federal prison guard, and sharing the top spot with cockpit crews was the job of a string quartet musician. I guess it was all worth the wait.

*

In the erratic rhythm of my life, the weekly writing of this diary offers me a calming and thoughtful personal reflection on both the micro and macro of my life. More and more people have been asking specific questions of me, via email, Facebook and through the comment sections, and I try to answer as many as I can, and incorporate big topics into the diary. I would like to invite readers to directly email me at GeigeBerlin@yahoo.com (the hotline email I began immediately after my violin was stolen earlier this year) with questions or topic suggestions.

Comments