Welcome to the new caring, sharing musicology

mainSlipped Discers have been sharing opinions from both sides of the fence on William Cheng’s forthcoming book and its advocacy of ‘a musicology that upholds interpersonal care as a core feature.’

William has asked us the share a sample of his book, which we do with pleasure. Here goes:

*

This is an excerpt from William Cheng’s Just Vibrations: The Purpose of Sounding Good (University of Michigan Press, 2016, foreword by Susan McClary), available both in print and Open Access. A version of this essay was presented at the 2016 Meeting of the Society for American Music in Boston, MA. Reprinted with permission from the University of Michigan Press.

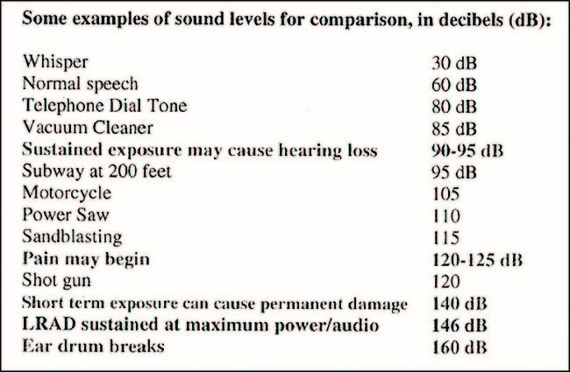

Arriving at the twilight of summer, we’ve witnessed yet another season of broken hearts and windows and formations and bodies and boundaries. Shouts of “Black Lives Matter!” have reached fever pitch amid civilians’ protests against racism, hate crimes, police brutality, and injustice. In addition to using batons, tear gas, stun guns, smoke grenades, rubber bullets, and other crowd-control tactics, officers in several cities have employed Long Range Acoustic Devices (LRADs), which can weigh over three hundred pounds and fire cones of noise up to almost 150 dB and 2.5 kHz.

Development efforts for the LRAD originated in the wake of the 2000 terrorist attack on the USS Cole in Yemen. Since then, the LRAD Corporation, based in San Diego, has sold its line of products to military and security personnel worldwide. Thanks to strong international business, LRAD’s revenues totaled $24.6 million in the fiscal year 2014, up 44 percent from $17.1 million the year before. As of today, more than seventy countries have purchased LRAD systems.

Protest and LRAD at the 2009 Pittsburgh G-20 Summit.

Protest and LRAD at the 2009 Pittsburgh G-20 Summit.

The LRAD Corporation markets its devices in benevolent, caring terms. Promotional materials stress LRADs’ utility for wildlife protection, emergency mass notification, public safety, and rescue operations (such as talking a suicidal person off a bridge or communicating with stranded hikers on a mountain). The websitestates, complete with emphases: “LRAD is not a weapon; LRAD is a highly intelligible, long range communication system and a safer alternative to kinetic force. But a blanket denial of LRADs as weapons runs counter to the maker’s proud claims about the devices’ potential to scare off sea pirates and overcome enemy combatants in wars abroad. “If [LRADs’] maker tempered its initial [weapon] metaphors,” Juliette Volcler points out, “it’s because this allows distributors to sidestep the U.S. and European prohibitions on weapons sales to China that have been in place since the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. It allows . . . the LRAD Corp. to publish glowing notices after its products are used to distribute information to survivors of natural disasters, such as in Haiti, or to counter anti-capitalist protesters in Canada.”

LRADs use a technology called piezoelectric transducers to focus sound waves into a narrow field of impact (hence their moniker of sound cannons). In January 2010, the Disorder Control Unit of the NYPD released a seven-page briefing on the LRAD. One section stated that “while the sound being emitted in front of the LRAD may be very loud, it is substantially quieter outside the ‘cone’ of sound produced by the device. In fact, someone could stand next to the device or just behind it and hear the noise being emitted at much lower levels than someone standing several hundred feet away, but within the ‘cone’ of sound being emitted.” Security forces and governing bodies to date have not subjected LRADs to extensive regulation, presumably because the devices fly under the radar as weapons in their own right. Page 3 of the “Briefing on the LRAD by New York City Police Department: Special Operations Division/Disorder Control Unit” (January 2010)

Page 3 of the “Briefing on the LRAD by New York City Police Department: Special Operations Division/Disorder Control Unit” (January 2010)

LRADs’ ability to focus sound into a narrow field doesn’t eliminate the risk of collateral damage. In any case, the promise of exactitude doesn’t make LRADs less problematic than drones (with purported capacity to carry out precision strikes) or sniper rifles (in the hands of a mass murderer). More generally, there’s a lack of research on LRADs’ injurious capabilities. Here’s Amnesty International’s report on the use of LRADs in the Ferguson protests two summers ago:

On the night of Aug. 18 [2014] at approximately 10:00 p.m., following the reported throwing of bottles at police and a group of protesters stopping in front of a police line in defiance of the five second rule, law enforcement activated a Long Range Acoustic Device (LRAD). The LRAD was pointed at [a] group of stationary protestors on the street approximately fifteen feet away. Members of the media and observers were likewise about the same distance from the device. No warning from law enforcement that an LRAD would be used was given to the protesters. After providing earplugs to a member of Amnesty International, a St. Louis County police officer says, “This noise will make you sick.” Several members of the delegation reported feeling nauseous from the noise of the LRAD until it was turned off at approximately 10:15 p.m. LRADs emit high volume sounds at various frequencies, with some ability to target the sound to particular areas. Used at close range, loud volume and/or excessive lengths of time, LRADs can pose serious health risks which range from temporary pain, loss of balance and eardrum rupture, to permanent hearing damage. LRADs also target people relatively indiscriminately, and can have markedly different effects on different individuals and in different environments. Further research into the use of LRADs for law enforcement is urgently needed.

On 12 December 2014, attorney Gideon Orion Oliver sent the NYPD commissioner a memo on behalf of several people who claimed to have been injured by an LRAD while protesting the Staten Island grand jury’s failure to indict the primary police officer involved in the death of Eric Garner. Oliver requested that the NYPD refrain from using LRADs until thorough and independent testing has been conducted, until guidelines have been drafted and published, and until officers have received appropriate training to operate these devices. But a hurdle in such pleas lies in a lack of public awareness and empathy. Unless you’ve been bombarded by an LRAD, it’s difficult to imagine or even believe the degree and nature of pain that this sonic artillery can inflict.

The fact that LRADs tend to leave few visible traces of injury on victims’ bodies doesn’t make the devices any less in need of regulation than, say, bullets and batons. LRADs are a sonorous smokescreen: because a relative absence of discernible wounds raises the victim’s burden of proof in a court of law, these devices require stricter, not laxer, operational guidelines. It’s too easy to write off an LRAD’s deployment as mere warning shots that precede escalation of true force.

In a video that shows a nighttime demonstration in Ferguson, we first hear the sounds of LRADs and police instructions; then we hear and see rubber bullets and tear gas lobbed into the crowd. No matter how piercing the LRADs may have felt to this crowd, our attention (as YouTube viewers here and now, as protesters then and there) necessarily jerks toward the bullets once they start flying. Because look:bullets. During violent confrontations, nonlethal weaponry can serve practically as a euphemism for prelethal. The announcement of a technology that’s unlikely to kill nonetheless augurs the presence of external force and the weighted options of consequent lethality. By the same mortal token, a tragic reality in the name Black Lives Matter is how it comes fueled by laments that black deaths matter—for it isblack deaths that repeatedly and horrifically make the news, inciting outrage and after-the-fact damage control.

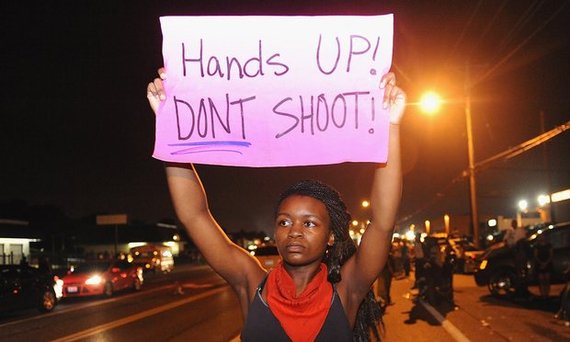

Photograph: Michael B. Thomas/AFP/Getty Images

Photograph: Michael B. Thomas/AFP/Getty Images

LRADs leave protesters with little choice but to cover their ears with both hands. There’s a brutal irony here given how one of the rallying cries of Black Lives Matter is precisely, “Hands up! Don’t shoot!” Many protesters in the above-mentioned Ferguson video already had their hands raised above their heads to signal their weaponless status and to decry police killings of unarmed individuals. Police actions that force protesters to cup their ears effectively strip the hands-up-don’t-shoot gesture of its symbolic charge. The raising of hands transforms from a deliberate sign of willful pacifism into a reflexive show of self-preservation. So beyond the capacity of LRADs to inflict harm, the devices pervert the protesters’ choreographies of resistance. They also drown out protesters’ words and music, overriding free speech and rendering dialogue among assemblies inaudible.

For the wielders of an LRAD, a major selling point is the clarity with which it amplifies the speech of those controlling it. The makers declare that “LRAD’s optimized driver and waveguide technology ensure every voice and deterrent tone broadcast cuts through wind, engine, and background noise to be clearly heard and understood.” Voices transmitted through the devices boast exceptional intelligibility and range. But are such clarion vibrations just when protesters’ voices are getting muted? In this case of asymmetrical conflict, should police have access to a technology that broadcasts crystalline instructions when the people’s calls for reform are going unheard?

Remember, folks: this is the new musicology.

Comments