Exclusive: My Life with Maria Callas

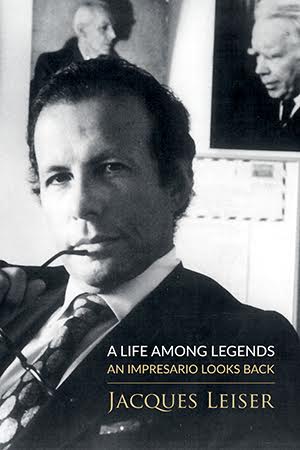

mainSlipped Disc is privileged to present an extract from the newly published memoirs of veteran artists manager, Jacques Leiser.

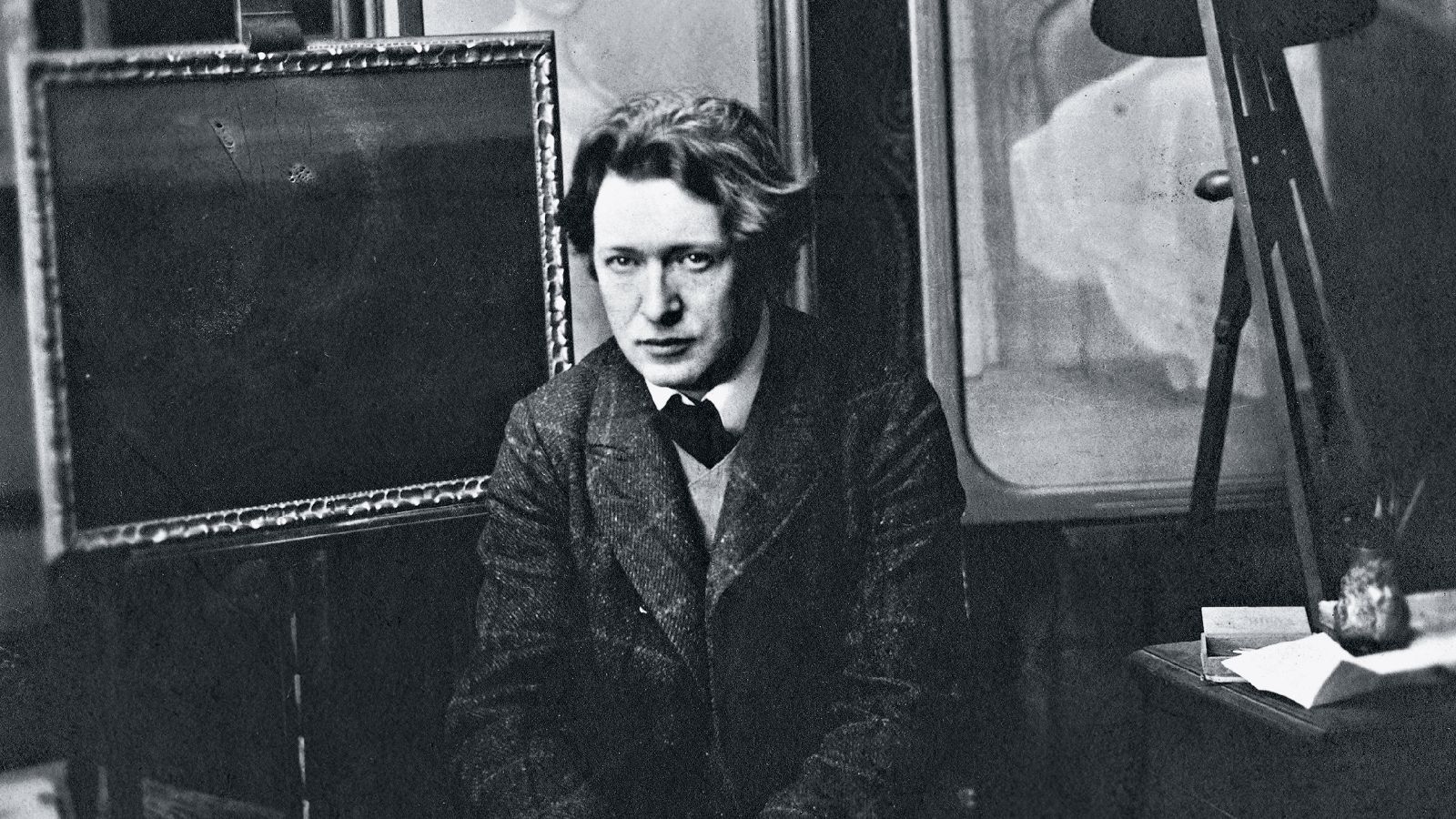

When I saw Maria Callas it was love at first sight. The first LP of hers that I heard – I still recall my excitement when I think about it – was her “Puccini Heroines” recital recording in which she sang “In Quelle Trine Morbide” from Manon Lescaut. I was bowled over by it. Callas recorded a large quantity of operas for EMI at La Scala during this period. The recordings usually took a month approximately, sometimes less, sometimes more. The recording sessions often had to be inserted during different periods, on account of Callas’s already heavy touring schedule throughout the world.

In April 1954 she sang La Sonnambula at La Scala. It was the first time I heard her live. I was there for the premiere. Without a free ticket, I could never have afforded to attend. After the performance I went backstage, was introduced to Callas, and congratulated her. Two days later there was a second performance, and I went back again. She looked at me and asked, “Didn’t I see you here at the premiere?” and I said, “Yes.” Then she said, “And you’re back again?” to which I replied, “Yes, and I’ll be here tomorrow as well.” She was simply astounded. I attended all ten performances; I couldn’t get enough. Each performance was unique, a new experience each time. Maria Callas was my absolute idol and one of the most inspiring artists I have ever met, one who gave everything for her art.

In time I became friends with her, and she was always very gracious to me. In addition to her extraordinary singing voice – which was easily recognizable even on the radio – Callas’s speaking voice was incredible. When I received telephone calls from her, I would be captivated by the first word she said. Her voice had a timbre like none other I have ever heard. I will never forget the mesmerizing impression she made with its smooth, velvety and warm quality, the beauty of her magical voice, her unforgettable nuances, as well as the power of her voice and incredible dramatic projection on the stage. She was absolutely unique and could not be compared with any other singers of her time.

The Callas I knew was very different from the temperamental diva portrayed by the media; I remember her as an artist totally dedicated to her art, thoughtful and kind to others, even people she knew only casually. She was thoroughly professional, always willing to redo recording takes or whatever was required of her, very cooperative, rarely temperamental without just cause, and a perfectionist. During the tiring Norma recording sessions in the mid 1950s, for instance, one of which lasted until 2 a.m., including a major shift in venue when the stage at La Scala was needed for something else, she didn’t complain, but her colleagues – some of whom were not as committed as she was – did show their irritation. EMI was obliged to order nearly fifty taxicabs to get the musicians home after this marathon session!

On one occasion, before a rehearsal at La Scala, she was asked to wait until the eminent pianist Wilhelm Backhaus finished going over a concerto on stage. Callas refused adamantly, saying, “I don’t care if it is Backhaus! I’m supposed to start my rehearsal at 3 o’clock. Tell him it’s over.” This was not temperament. As a professional she did not want to lose five minutes of her working time. She needed every minute of it. She was a true perfectionist. Callas was mesmerizing, a far greater artist on stage than any of her colleagues. She immersed herself in her roles. As an example, while rehearsing Medea at La Scala we would go to a nearby café, where once during a break from a dress rehearsal, someone asked, “Maria, what are you holding in your hand?” She was still holding a dagger! Even during a coffee break her mind was still on the stage.

A rather poignant incident illustrates a side of Callas that is rarely mentioned, her emotional warmth. During her 1962 German tour with the conductor Georges Prêtre, she was singing when Prêtre cued both the singer and the orchestra incorrectly. Callas signaled him, calmly and unobtrusively so as not to embarrass him, to go back several measures. After the performance, Prêtre disappeared into his hotel room and avoided the reception. Callas inquired, “Where’s Georges?” and asked me to take her to his room. We left the reception and went to Prêtre’s room, where she called out, “It’s Maria! Open the door.” He opened it, dressed in his bathrobe; he was very upset. She sat him down on the bed and lectured him in a motherly fashion, “You’re an excellent conductor… it could happen to anybody.” I was profoundly moved: she was consoling him; a typical prima donna would have been screaming that he had ruined her performance. I was witness to another instance of her kindness during that German tour. One day I brought some mail addressed to her including a letter from a former member of the La Scala chorus, whom she did not know, who had sung in some performances with Callas. The singer had since married a German and was living in Hamburg. She had never forgotten those La Scala performances and had tried but failed to buy tickets for the gala concert that was scheduled for Hamburg during the tour. Not only did Callas request two free tickets for her former colleague, but she replied personally with a friendly note.

When I left EMI in 1964, I wrote personal notes saying goodbye to various artists and all my friends and associates, including Callas, mentioning that I was no longer associated with EMI. Shortly afterwards, Callas sang Norma in Paris before a glittering audience including political dignitaries and celebrities such as Brigitte Bardot, Yves St. Laurent, and others. At the end of the performance I went backstage to congratulate her. She was still on stage, not in her dressing room. When she saw me, she embraced me – while she was still going out to take curtain calls – and said, “Oh, I kept your note and I’m so sorry to hear you have left EMI! What are you doing now?” It was as if we were sitting together alone at a café. At such a moment of success, how could she remember if I had written her a note three or four months before? She was a generous, caring person. Unfortunately, despite her great talent and dedication, Callas frequently experienced vocal difficulties. EMI had brought its most advanced recording equipment to Italy, but La Scala had no provisions for a control booth with a direct view of the performers on stage. If Walter Legge, the legendary British chief producer for EMI records (and the husband of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, another of the great sopranos of the time) heard something unusual occurring, he would ask me to go on stage to investigate. One day he asked, “Who is that mezzo or alto making those awful noises down there? Go and tell her to leave.”

Unfortunately, it turned out to be La Divina herself in a moment of vocal crisis. The fact was that some days Callas wasn’t in voice. It just wasn’t there. She knew it – and we knew it. At those times she would just pick up her bag and say “Ciao!” Again, it was not a matter of temperament. We knew she couldn’t perform, so we simply worked on some other section of the recording. Although I was not at the 33 infamous Rome performance of Norma attended by the Italian president – the performance that Callas abandoned after the first act – I am quite certain that her voice simply left her. Of course the press seized upon this to portray her as temperamental. Throughout her career, Callas struggled in trying to control her voice with its unusually large range. She suffered considerably, being aware of her inadequacies. Her voice sometimes was uneven between the registers, but she compensated for all the vocal imperfections and persisted where others would have given up. Callas used to phone me late at night from her hotel room when she could not unwind or fall asleep. She would sometimes talk for nearly an hour, about herself, her life, her problems, etc, then would say that we had better get some sleep. Invariably she ended these conversations saying, “Pray for me that I’ll awake tomorrow with my voice.”

(c) Jacques Leiser

Thanks for this very interesting preview of Jacques Leiser’s memoirs! He represented most of the Soviet artists and others from countries behind the Iron Curtain in the USA during the cold war period (Richter, Oistrakh, Berman, etc.) I think there will be some very interesting tales to tell about them!

Oistrakh (father and son) and Richter were represented by Sol Hurok throughout their North American appearances, as were the majority of touring Soivet artists. Berman and Davidovich were represented by Leiser—Davidovich after emigrating to the USA.

You are right, sorry for the confusion. I was going to post a correction, but you got there first!

Is this only out on e-books? I can’t find a hard copy mentioned anywhere.

The Callas material is hardly new, even if from a different perspective. Personally, I’m more interested in his “my life with Lazar Berman”. That has surely to be one of the more bizarre tales around.

La Sonnambula was NOT April, 1954. It was a year later, March, 1955.

You can hear the impresario speak: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=uzYcfHu_xtQ

Norma was recorded at the Cinema Metropol in Milan, not at Scala.

The “infamous Rome performance” was in 1958. “33” in incorrect. Typo?