The blind spots of Pierre Boulez

mainMax Raimi, a viola player in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, played with Pierre Boulez for 25 years and greatly admired his human qualities. But some of his musical choices left Max vexed. Here, in an essay for Slipped Disc, is his thoughtful assessment of a musical giant and his myopia.

!["Hommage à Pierre Boulez zum 85. Geburtstag" Pierre Boulez, in der Berliner Staatsoper Unter den Linden, Berlin, franzoesischer, Komponist, Dirigent, Musiktheoretiker, Avantgarde, Musik, [Das Foto ist ein Lichtbildwerk i.S.v. §2 Absatz 1 Ziff.5 UrHG, Nur redaktionelle Nutzung, Nutzung Honorar-& MwSt. pflichtig! Weitergabe an Dritte nicht erlaubt. Wir uebernemen keine Haftung bei einer evtl. Verletzung Rechte Dritter! Es gelten unsere AGB. t.bartilla@googlemail.com, Koepenicker Landstr. 150, 12437 B e r l i n, Bankverbindung: Thomas Bartilla, Ing-Diba, Kto. 5526039061, BLZ 50010517, Tel. + 49 178 55 60576 ]Staatsoper Unter den Linden, Berlin, Nutzung für interne Zwecke der Staatsoper unter den Linden Berlin, kostenfrei und ohne Einschränkungen, [Das Foto ist ein Lichtbildwerk i.S.v. §2 Absatz 1 Ziff.5 UrHG, Nur redaktionelle Nutzung, Nutzung Honorar-& MwSt. pflichtig! Weitergabe an Dritte nicht erlaubt. Wir uebernemen keine Haftung bei einer evtl. Verletzung Rechte Dritter! Es gelten unsere AGB. t.bartilla@googlemail.com, Koepenicker Landstr. 150, 12437 B e r l i n, Bankverbindung: Thomas Bartilla, Ing-Diba, Kto. 5526039061, BLZ 50010517, Tel. + 49 178 55 60576 ]](https://slippedisc.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/pierre-boulez-85-birthday-barenboim_d_jpg_720x405_crop_upscale_q95.jpg)

I first played under the baton of Pierre Boulez more than a quarter of a century ago, shortly after I joined the Chicago Symphony. I always admired him as a human being. He was kind, brilliant, generous, and by all accounts a great and loyal friend. On more than one occasion he rescued the Chicago Symphony on short notice after other conductors had to cancel on us. Indeed, he and Bernard Haitink stepped in to steer the orchestra’s artistic fortunes following Daniel Barenboim’s abrupt departure in 2006. All of us in the orchestra are very much in his debt.

But in addressing his legacy, I feel that another aspect of his life must be acknowledged. As a polemicist, he had a profound effect on how we thought about music for much of the 20th century and beyond. On the whole, I think this effect was far from beneficial.

In an essay that dates from 1980, the composer Ned Rorem describes a lecture that Boulez gave on the subject of Debussy’s Etudes. Boulez, according to Rorem, characterized an E-natural in the eighth bar of the Etude-in-Fourths as “a veering from the key center”. Rorem pointedly disagrees, hearing it as “a ‘blue’ note”. Indeed, Rorem hears “the whole lush piece as a jazz improvisation.” Boulez’s premise, Rorem tells us, is that “all roads lead to dodecaphonism” (i.e. to twelve-tone atonal music).

Debussy was one of Boulez’s heroes and so, in Boulez’s view, his music must be heard as a harbinger of the glorious atonal world to come. Rorem’s essay reminds me of something I read back in my college days, Herbert Butterfield’s The Whig Interpretation of History. Butterfield brilliantly takes the conventional wisdom of the historians of his time to task in this brief book from the 1930s. He feels that they regarded history as a teleological phenomenon; mankind was “progressing” towards a world-view that, coincidentally, was the world-view held by these historians. All previous modes of thought, then, were judged as enlightened or reactionary according to how closely they resembled the views of the Whig Historians.

Unfortunately, a teleological narrative is extremely problematic in regard to artistic achievement. Einstein could supersede Newton and antibiotics clearly work better than leeches. But can we truly “progress” beyond Bach or Mozart? Ironically in a man who was famed for his “modernism” Boulez’s faith in man’s eternal journey ever closer to perfection seems a quaint 19th century mindset. It is a way of looking at the world that was, for most of us, discredited by the nightmare of the 20th century’s totalitarian conceptions. We learned the hard way that the rational mind of man was not inexorably advancing toward a utopian future.

Like any good Whig, Boulez picked good guys and bad guys from the pantheon of composers. He favored those whom he could fit into his own narrative, that the entire history of western music was a long struggle to throw off traditional tonal practice. Not many composers before Debussy earned his approval. The only composer born before 1860 I can remember him conducting more than once in the 25 years I played under his baton is Berlioz. Even in the 20th century, there was no shortage of composers who did not conform to Boulez’s March of Progress, and were thus unworthy of his consideration.

In an interview with the Chicago journalist Dennis Polkow on the occasion of his 85th birthday, Boulez went to some length in trashing Dmitri Shostakovich:

“I heard [the First Cello Concerto] twice over the years, and I am not saying that it made me physically sick or anything like that, but Tchaikovsky was more radical than Shostakovich. I heard the Fifth Symphony a few years back here in Chicago; it is so conventional. And Symphony Fifteen, this business of long quotes from Rossini, what a poor excuse for some imagination. If we are to play Shostakovich, why not Hindemith?…

You know, in the history of music, there are composers without whom the face of music would be completely different, and composers whom if they had never existed, it would have made no difference whatsoever.”

This is as eloquent a manifesto as one could want for the world-view and unstated assumptions of the Whig Historian. Composers, Boulez implies, are to be judged by whether or not they change “the face of music”, and it is clear what manner of changes were required to earn his approval. Whether or not music is beautiful or enables the audience to experience something that it finds meaningful and valuable is apparently beside the point.

In addition, it is dismaying to see Boulez, who was ordinarily so kind and gracious, condemning Shostakovich’s Fifth for being “conventional”. Shostakovich was nearly destroyed for writing music that displeased his Soviet taskmasters. He wrote the Fifth Symphony in the style he did because his career and perhaps even his life depended upon it. To condemn this music for being “conventional” is rather like telling a political prisoner, “You know, you really should get out more!”

And yet, can’t the argument be made that Shostakovich was, in his way, more progressive than Boulez? The “business of long quotations” that Boulez ridicules in the 15th Symphony always struck me as an inspired use of “found objects”, which, in a work that dates from 1971, presages such contemporary visual artists as Alan Rankle and Tracy Emin, not to mention the samplings of preexisting recordings that are often used in rap and hip hop. There is nothing comparable in the music of Boulez. Indeed, I find that his angular melodic shapes and the thoroughgoing dissonance of his harmonies never entirely left the sound world of the Second Viennese School, notwithstanding the superior sophistication and flexibility of his serial techniques, the often daunting rhythmic complexity, and the greater variety in timbre achieved through electronic technology and the subtlety and complexity of his instrumentation.

There were other blind spots in Boulez’s aesthetics that affected his view of Shostakovich. An element of Shostakovich that Boulez could not even acknowledge, so foreign was it to his own viewpoint, was the Russian’s use of popular elements in his music, of folk materials, military marches, and dance rhythms. In this, Shostakovich (and Mahler and others before him), foresaw the melding of high and low art that is so much a part of our present artistic landscape.

I always felt that this limited Boulez when he conducted composers such as Bartok and Mahler, whose styles were deeply affected by popular elements and folk materials. One work I performed with him countless times was Mahler’s Seventh Symphony. In the third movement, which to me is thebes t music in the symphony, the climax is a crushingly vulgar fortissimo waltz theme grotesquely orchestrated with an appallingly banal accompaniment. Mahler marks the music “Wild”, and it should be horrifying. I always imagine Mahler as a neurotic child encountering drunken, brawling soldiers at his father’s tavern near their barracks in rural Bavaria. It would be hard to conjure a more harrowing depiction of Hannah Arendt’s “banality of evil”. But in the hands of Boulez it always came across as bizarrely elegant–not too fast, not too loud, very accurate. It would have been hard to miss more completely the point of the music.

Inexplicably, more than a few critics accepted his view reducing Mahler to a mere way station on the road to Schoenberg (and Boulez). In a review from Oct. 7, 2010 of a Boulez performance of Mahler 7 with the Chicago Symphony, John Von Rhein, of the Chicago Tribune wrote: “It took the alert ear of Boulez to recognize the distant footfalls of the Second Vienna School in Mahler’s weird harmonic clashes.”

Indeed, critics almost universally praised Boulez’s Mahler interpretations, even of this berserk symphony, for their Apollonian vision. The logic escapes me. Would we praise a diva for a similarly cerebral depiction of the Mad Scene in Lucia? “By not letting herself get overwrought, and calmly singing as if she were at a Presbyterian Church service, the soprano let us really see the melodic lines and harmonies as Donizetti wrote them…”

Would we praise an actor doing Lear for his emotional detachment, and marvel at how he seems so unaffected by his daughters’ betrayal of him that for once we really see Shakespeare’s words as they appear on the page? In passages such as this excerpt from the Seventh, vulgarity is at the very heart of the music; it wallows in the popular culture of Mahler’s time. It never seemed to occur to Boulez that this music must be tied to the world that inspired it outside of the notes on the page.

This is another way in which the world left Boulez the “modernist” behind. His aesthetics were almost obsessed with stylistic consistency. He derided composers past and present for using preexisting structures and tonal schemes with which to organize their material, rather than reinventing the structural wheel with each new work according to the nature of the material therein. In his essay Debussy and the Dawn of Modernism he lauds his hero: “What was overthrown was…the very concept of form itself, here freed from the impersonal constraints of the schema…demanding a technique of perfect instantaneous adequacy.” I’m not sure what “perfect instantaneous adequacy” is. Maybe it works better in the original French.

Later, this essay is even more opaque, at least in translation: “Motion, the instant, irrupt into his music, not merely an impression of the instant, of the fugitive to which it has been reduced, but really a relative and irreversible conception of musical time, and more generally, of the musical universe.”

In any case, we get the idea. Each piece of music must create its own form according to the material being manipulated; it must owe nothing to anything that exists outside its own microcosm. This unfortunately leaves out a lot of the way the world actually exists in our time. If I walk a mile or so north from the Chicago Symphony’s hall, I see a joyous cacophony of architectural styles, promiscuously borrowing from millennia of human history—neo gothic structures like the Tribune Tower, Frank Gehry’s post-modernist conception at Millenium Park, a few Modernist rectangles, Renzo Piano’s lighter-than-air confection for the modern wing of the ArtInstitute and so on.

Many composers since the mid-20th century have reflected this aspect of our world in their music. The Soviet master Alfred Schnittke even coined a term for it: Polystylism. The Chicago Symphony currently has two brilliant young composers-in-residence, Mason Bates and Anna Clyne, who write music that is a glorious mash-up of, among other things, club music dance beats, electronic wizardry, and classical techniques both contemporary and anachronistic. It seems to me that this is the future, and Boulez’s paeans to Debussy’s structural integrity are very much the past. Yet still, it is almost impossible to find anything written about Boulez that doesn’t pay homage to his cutting-edge modernism.

The image of the creative artist as misunderstood genius who is appreciated only by posterity is a cliché. Like many clichés, it has some elements of truth to it. Mahler, Schubert, Bruckner, and Berlioz are certainly appreciated more today than they were in their lifetimes. With Boulez, though, we have a new phenomenon. Here is a composer that started as an enfant terrible urging us to blow up opera houses and ended up a stalwart Establishment institution—and yet never had to write any music that mainstream classical music audiences actually wanted to hear to achieve his climb to eminence.

Indeed, it became somehow bad form to point out that his music is not very successful with the public. In January 2010, the Chicago Symphony sponsored a chamber concert featuring many of his works in honor of his 85th birthday. I was told that the Chicago Architecture Foundation, which has the good luck to be located next to Symphony Center, was overrun with literally hundreds of patrons fleeing the concert at intermission, still clutching their programs. I was told this by one of the refugees. Naturally, this mass exodus was not deemed worthy of mention in any of the press accounts of the event, just as there is a polite silence in the local press about the banks of empty seats at the Chicago Symphony that still result from any program in which the music of Boulez is prominent.

How could Boulez come to such prominence while composing music of such limited appeal? I believe that it was his Whig sensibility, and his success in getting the rest of the world to buy into it, that enabled him to achieve this. The powers that be in classical music decided that Boulez was right. Atonality was the only true path, the goal that we had been unwittingly striving toward ever since the first Gregorian chant. If you were writing tonal music by the middle of the 20th century, you were irrelevant, or, as Boulez put it in his notorious 1952 essay “Eventuellement…”, “useless”. So it didn’t matter whether audiences actually liked it—that was the new music they got. History and Progress had allowed us no alternative.

For a couple of generations after World War Two, composers who employed elements of traditional tonality became endangered species at the music schools of our great universities.

Of course it is simplistic to say that Boulez by himself caused this. But there was no denying his power as a polemicist—and the power of his considerable personal charm. His Whig narrative became accepted wisdom. Tonality, and music that communicated to the traditional classical audience, were consigned history’s ash heap.

This was a tragedy for American music. Whenever I perform Copland, or Bernstein, or Barber, I think of how the 1940s must have looked to American musicians at the time. Copland was an established talent, basking in the great success of his Third Symphony and the ballets. Bernstein had arrived on the scene in a big way, composing the Clarinet Sonata and On The Town in that decade. Barber was hitting his stride, and there was a phalanx of highly skilled composers of the second rank on hand, such as Walter Piston and William Schuman. Our nation was poised like Bohemia at the time of Smetana and Dvorak, or Russia in the heyday of the Mighty Five, to tell our story in classical music, to create an indigenous national school. It was not to be. Barber’s lyricism got him laughed off the stage. Copland was cowed into writing twelve-tone music in the 1950s. And Bernstein had his greatest successes on Broadway and on the podium.

One of Boulez’s staunchest allies was my old Music Director, Daniel Barenboim. It was under Barenboim’s auspices that Boulez was named Principal Guest Conductor of the Chicago Symphony, and Barenboim frequently programmed the music of Boulez and his acolytes. He never deigned to conduct the 20th century composers Boulez would have described as “useless”, unless he was compelled to accompany something along the lines of a Prokofiev concerto. He was pretty open about his disdain for the more tonal currents of our time. But one time, he did condescend to conduct Samuel Barber. It was our first concert in Chicago after 9/11, and he selected Barber’s Adagio for Strings to commemorate the tragedy.

I always wanted to ask him why, when it came time to bring people together in a shared emotion (Wasn’t this a prime motivation for why humanity has always turned to music in the first place?), his esteemed Schoenberg and Boulez suddenly weren’t up to the job and he had to resort to the benighted modal harmonies of Samuel Barber. Doesn’t this tell us something profound about the limitations of the “progress” that Pierre Boulez always insisted we had made?

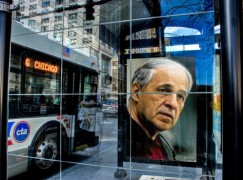

Boulez on a Chicago bus stop

Not so much a Whig, as similar to Marxists and “historically inevitability”. If the facts don’t fit change the facts.

Which “Marxists”? These? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constructivism_(art) Or these? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rm6M0Vy4Nw8 Or these? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_realism Or this one? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P81-_E1C_ck

There is, actually, maybe one thing that Boulez does have in common with all the artists who ever, in one way or another, associated themselves with Marxism. They’re all hated – some for aesthetic reasons, some for ideological reasons, some both – by the ACTUAL heirs to the Whigs: the cheerful neoliberals who, even after having been exposed as totally incompetent as a ruling class 8 years ago, still believe so unquestioningly in their own version of historical inevitability that they don’t even realize that’s what it is – “a joyous cacophony of architectural styles, promiscuously borrowing from millennia of human history.”

What do you suppose Graham Clark was trying to say?

Excellent article. Boulez had no idea how to make music “breath”. He was basically a time beater. Excellent for Stravinksy, tragedy for Mahler! Personally, I never heard a work by Boulez that peeked my interest enough to hear it a second time. His complexities are a curiosity, interesting to observe, one can appreciate the brain that created them, however, if the music doesn’t touch the soul, what is the point of it?

Perhaps, but he certainly learned how to allow orchestras to breathe, which makes his breathtakingly sensual re-recordings of Debussy in Cleveland irreplaceable. In music he had been conducting the longest, his growth and coloristic sensitivity was notable. The entire concept, that a conductor must be a curator of the entire repertoire is nonsensical. Generalist conductors tend to be the least interesting we have. The idea of balancing repertoire through different conductors was not unique to Chicago, the rise of Boulez as an international conductor was facilitated by a similar arrangement with the a great George Szell, who possessed a similarly proscribed repertoire.

Lucky author who was able to experience such great leadership!

Well said. Considering in the 70s he didn’t have a good word to say about symphony orchestra’s he made a he’ll of a lot of money conducting them.

I agree totally, Boulez had no sense of phrasing; a stiff, uninteresting, uninspired, sexless, unhappy man. To be forgotten ASAP.

I admire people who still can talk what they really feel and think about avante-garde music in this era of a crazy over-PC. The musical world has struggled through several eras of modern composers writing without being questioned on their aeshtetic values. And Boulez in his country and worldwide was a HUGE part of this problem.

Now that those giants are gone it’s time to be more balanced and maybe, just maybe we’ll recover some of the audience we lost during those years.

Let’s all be more brave like the author of this essay and say publicly what kind of music we want to perform and hear. When i talk privately with members of a fine orchestra – they nearly all say they would love to avoid playing most of Ligeti, Stockhausen, Shnittke, Berio and Carter. But they would never admit that on the record. And that is a problem. Boulez is part of the reason why those people scared to speak out loud.

All VERY true.

PB was part of the totalitarian mind set of the worst aspects of the last century. And the most disturbing thing about it, has been – and still is – that any person with some intelligence and cultural awareness left, could see (and hear) that.

The article is nailing the problem nicely. And as PB’s charm is concerned, let’s not forget that also Hitler and Stalin could be really charming and ‘warm’.

PB has been taken much too seriously all along….

http://subterraneanreview.blogspot.nl/2016/01/notes-on-boulez.html

I’m sorry, but this is idiocy. How many “victims” of the Boulez “tyranny” are lying in unmarked graves throughout Europe and America?

Perhaps history will remember Boulez as the Khrennikov of French music.

Wow! I am actually surprised you brought up that name. I’d only wish as a Russian that Khrennikov would be remembered even a little. He did a lot of bad things. But some compositions are… childishly nice, I would say. Two violin concertos for instance.

Andrey, that’s assuming that Khrennikov actually wrote those violin concertos.

And any doubt that he did so would be contingent on assuming that Shostakovich wrote Testimony.

I know, metaphor is difficult. It’s about an utopian mind set, shared by marxism, communism, fascism, modernism: the longing to create a pure world, a pure society, a pure art, and to get rid of all those elements which hinder the overcoming of limitations. At the heart it is the alluring idea of revolution which cancels in one bang all pressures of reflection, consideration of contradictions, nuance, different points of view, and thus create space for the type of people who find thinking-through things too difficult and too time consuming. And in music, the illusion that there exists something like ‘progress’ in the arts, was the most damaging.

http://johnborstlap.com/the-killer-myth-the-fallacy-of-progress-in-the-arts/

See my post on Kenyon Cox’s “The Illusion of Progress.”- May 17 at 3:51 pm

Louis Torres, Co-Editor, Aristos (An Online Review of the Arts)

There is nothing that enhances and enriches an argument so much as a Hitler (and/or Stalin) reference. As for calling Boulez “totalitarian”, it makes a mockery of Boulez, totalitarianism, and most of all, of the author of this comment. In fact, it is so laughably wrong that it would be comic, were it not all-too-common verbal inflation.

For your information, totalitarianism is NOT utopianism, messianism or progressivism. We have different words for different phenomena, because it enriches language and thought and prevents grossly ineffective and caricaturing metaphors. Yes, totalitarianism did have an immanentist messianic element, but also much more than that. You may want to have a look at works such as Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Karl Löwith, Meaning in History, Eric Voegelin, The New Science of Politics, etc. If the only thing you retained from George Orwell’s depiction of totalitarianism in 1984 is the belief in a perfect utopian future, I’m afraid you missed the point.

Any parallel between Boulez and Hitler/Stalin only covers the author in ridicule, and displays the breadth of his ignorance when it comes to political ideology, political theory, and the history of ideas.

Being honest, the commenter above did not make a Hitler refence per se, he merely brought him up in a same comment.

There is something like a ‘totalitarian mindset’. Maybe there is a dictionary around that could clarify the term?

PB said himself: ‘I’m a 300% Leninist’. Lenin, it may be noted, had a totalitarian mindset. PB had, also when very old, a totalitarian mindset, as his indignation (in 2012) about critique of french modernism at a lecture at the Institut de France shows and his subsequent advice to a fellow composer to publish a loud protest against the freedom of speech so abused at the Institut. (This is meant as irony, in case the point is missed.) Totalitarian minds are against pluralism, against freedom, against real intellectual debate, and for power, streamlining, and suppressing of dissidents and the competition.

It is wholeheartedly to be recommended to try to understand the nature of discours before exposing one’s unfounded and pointless aggression.

Again, I have no idea what you’re referring to with your “totalitarian mindset”, nor where you’re taking it from, but it is not totalitarianism. That is called dictatorship. To give you the one-line, undoubtedly incomplete definition, totalitarianism refers to the subsuming of the totality of existence into one concrete political manifestation which becomes the arbiter of human existence. Examples include the Nazi Party in Germany and the Communist Party in the USSR, or the regime depicted by Orwell in 1984.

As for that (unsourced and uncontextualised) quote about Lenin, what exactly is Boulez referring to? There is more to Lenin than the totalitarian aspect; besides, expressing appreciation for a totalitarian figure does not make one a totalitarian. You’ll find that many, if not most, Leninists eliminate the totalitarian aspect of Leninism when transferring it into non-hegemonic political systems.

Finally, as for freedom of speech, you’ll find that the suppression of freedom of speech is a feature of many dictatorial, authoritarian regimes/figures around the world, which are not totalitarian.

So again, nice try, but you are clearly deliberately confusing terms in an attempt to blacken Boulez. Call him uncompromising, dogmatic, even authoritarian if you will, but again, calling him totalitarian makes a mockery of totalitarianism, and of yourself. You draw misleading comparisons on totally incorrect bases.

Ligeti ?! Come on ! His orchestra pieces are marvelous for the audience and also fun to play ! Come on …cool down

Boulez suffered from a very French trait, DOGMATISM.

This very same dogmatism can be seen in French politics and is at the root of so much that has harmed and ruined France. To think that today, in 2016, 27 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the fall and failure of communism, if you turn on a French political debate on television, you will still have several people espousing that the only way forward for the country is communism, state ownership of enterprise and collective state-run farms! They will debate these ideas, as if they were just invented yesterday, making little or no reference to past history, past failures and the fact that it would make France even less competitive than it already is. No, they will go on and on, for hours, railing about the evil capitalists, evil competition and how France can lead the way with an egalitarian system that punishes the rich and successful.

France, while an interesting place for a tourist, is a living anachronism, ever more disconnected from reality, with a myopic view of everything.

Pierre Boulez was a pure product of this dogmatic and idealistic French education and having the power that he did, was able to bring it to a wider audience. There are millions of similar Pierre Boulez’s in mindset everywhere in France, which explains its demise and current state of crisis and inertia.

Quoted without comment.

To make a purely political point here: the left in France are very good indeed at promising Utopia Now and then, when they have to come up with the goods, finding all kinds of excuses why The Promised Land is still millions of miles away. Look at what Mitterrand did in the 1980s and how he had to row back furiously, after insisting he wasn’t diverting from his original path. And now take a look at what Hollande is doing…… History often repeats itself, but in France in quite ugly ways.

Excellent comment, which jibes with the two powerful, insightfu,l comments of John Bortslap.

Boulez belongs to that French generation which grew up in the early 20th c. after WWI (and the Bolshevik Revolution), and became enamored with socialism, communism, totalitarianism, and all forms of dictatorial governance of the masses, believing that they had a direct line to the spirit of history, and also fertilized the grounds that gave rise to post-modernism.

The same tendencies could (and still can) be seen in other French-style critical studies of art (Andre Malraux), politics, economics, even philosophy (Sartre, de Beauvoir, etc.), which have impregnated the teachings of top professors in French academia.

As a French/American educated writer, I can see too clearly how unfortunate it has been that all this French intellectual, artistic, and ideological ratiocinations have been taken so seriously by American artists, writers, and scholars. The French have been selling fraudulent intellectual and artistic merchandise that the American elite has been too eager to embrace and buy.

But, luckily, if all were affected, not all were deceived. And Max Raimi is one of those who came through his own limited, but personal, experience to the realization that Boulez was just another one of those great French utopian system-weavers.

Ooh boy, we’ve got a lot of warriors for capitalism here.

Roo, you’re confusing French academia with French academics who are influential in America, and confusing Malraux and Sartre (who have been out of fashion in America for 40 years) with Lacan, Derrida, Foucault, and Baudrillard.

Derrida, Foucault and Baudrillard suffered from some affliction in the brain. Their postmodernist / structuralist nonsense has been brilliantly (and wittily) refuted by Roger Scruton in his ‘Modern Culture’ (Continuum 1998, 2000), chapter 12. Criticizing these intellectually dishonest quasi-thinkers has nothing to do with capitalism but is a defense of human intelligence and civilization. Where academia is infected with this quasi-thought, the result is intellectual suicide.

I hate Foucault as much as you do – actually more; we’ll get to that in a minute – but lying to ourselves isn’t going to accomplish anything. Everybody’s infected with his ideas now, including his critics, and if we’re ever going to break the spell, it’ll take something a lot stronger than the various bovine Analytics who purportedly “refuted” him in the ’90s – with the minor flaw that they failed to make people pay any less attention to him than previously.

The capitalism cheerleading is a separate issue. Foucault was a cheerleader for capitalism too. That’s the joke: You think you hate Foucault, but you agree with him about capitalism, AND you agree with him about the claims of Modernists such as Boulez.

Graham Clark:

No I don’t. I included all this French school of abstract manipulations that flourished after WWII and the German occupation of France, in my “etc.”.

I didn’t want to go through the exercise of listing all those “schools” (in reality only followers of one given leader, a so-called guru-“thinker”) and differentiating all those French flavors of the decades.

They are all produced by the same technique of massaging abstract ideas to relate them to the political/scientific climate of their time into opaque, mysterious, and often incomprehensible or absurd mental concoctions.

There are many more of those French intellectuals than the few you mention.

The French are taught the rudiments of such massaging in schools, then it gets polished at the university level, and the brightest or cleverest go on writing books and producing PhD theses. Most of it is not just hot air, although it feels like it, but intellectual masturbation or massaging vaguely related to the latest vogue concepts and theories produced by recent scientific discovery, political and religious trends whose major concepts are borrowed for their new Lego-like constructions. Learn the few new arcane concepts produced by the age, and then play with them for your constructions, pretending to offer a new, revolutionary worldview. This is the way to build your name, and be hailed as a new guru yourself.

Socialism and communism, marxism, and the cult of the Bolshevik-style revolution have been, from the start of the 20th c., major sources of ideas for those brains, easy to assimilate, easy to amplify and distort, but not the only ones, far from it.

Some of the smartest French writers have moved to the States, where the market of consumers is much larger, especially among all those college professors in the boondocks who were delighted to get some more European material to chew on for their own books, and a great opportunity to legitimate interesting trips to France and Europe.

I have read more than my share of these French ratiocinations (and still repent for wasting so much time reading stuff like Lacan’s or Derrida’s, a major risk to anybody’s sanity), and when I moved to Harvard, it was mostly in reaction to the twisted, perverse methods and phoniness of this abstract style of thinking.

None of those “thinkers” were even remotely interested in studying how the Western mind, or even the French mind works in an experimental and objective way. The most they produce is a huge amount of speculations using artificial language based on a collection of anecdotes and borrowed concepts to generalize their invented description of the working of the thinking brain in its various social activities.

There’s nothing really to gain or learn from wasting one’s valuable time reading their elucubrations, unless it is to write more articles and books about how phony they are — an exercise that American academics particularly enjoy, as it gives them a wonderful subject to enrich their published bibliography and a wonderful pretext for European trips. Tony Judt at NYU, for instance, made a specialty of this dedication in building up a highly successful academic career.

tl;dr

I read it and appreciate your post very much.

Excellent essay, although I do not agree with its conclusion. Two thoughts:

1) Many musicians and audience members enjoy Barber and Schoenberg, Nono and Prokofiev, Reich and Haas. In the Boulezian world view, music flowed in a rigorous stream of musical progress from late Beethoven via Berlioz, Wagner, and Liszt to Debussy, Bartok and the Second Vienna school and then on to Messiaen, Boulez, Ligeti etc. Dismissing the quality of any composers outside this clearly delineated route is dogmatic and blind to the complexity and eclecticism of all aspects of the 20th century.

2) Doesnt’t it seem equally narrow-minded to suggest that all great music has to have wide audience appeal? The Barber Adagio, Shostakovich 5 or Mason Bates might be “accessible” but shouldn’t we encourage and support intellectual rigor and radicalism even if only a small elite of listeners can fully appreciate it? I know I’m opening Pandora’s Box but the definition of great art is not how well it sells.

In the end, everybody is entitled to not enjoy Shostakovich; but chastising him for not being modern or radical enough is petty and, in the end, an obsolete discussion. Equally, if we only performed composers beloved by subscribers we would be neglecting a lot of wonderful music. What about that kid who stayed until the very end of the Boulez chamber program and who’s life was changed by hearing it? We owe it to her, too.

“…… the definition of great art is not how well it sells.” That is very true. But one cannot conclude from this that music that does not sell well, must THEREFORE be great music, and this was a key misunderstanding of modernism. The central performance culture of classical music hangs on the fragile relationships between three parties: composer, performer and audience, and you cannot leave out one of them.

“…… if we only performed composers beloved by subscribers we would be neglecting a lot of wonderful music.” Alas, that is the current situation, in general. But there is a sound reason why certain pieces return again and again and don’t wear-off. Unfortunately, they also provide excuses for lazy and conventional programming.

Visit the site of the Future Symphony Institute for interesting and clarifying information and essays on questions like this:

http://www.futuresymphony.org

Spot. On.

The emperor has no clothes, never did, and how refreshing it is to read the truth.

Completely agree.

But an establishment of a few powerful ‘musicians’ and critcs have been forcing garbage down our throats. This problem shows no signs of abatement.

There are fewer and fewer concerts where there won’t be garbage on the program that critics will rave about. If the garbage isn’t there, the critics will bash it. Very sad.

Understandable reaction, if referring to works like PB’s. But the problem is, that a work of sonic art is played in a program of music. Sonic art entirely exists in terms of pure sound, while in music the sound is a carrier of psychological / emotional meaning, which is a different layer. Listened to as music, sonic art is an alienating experience; listened to in a sonic context – i.e. a program entirely made-up of sonic art – it comes into its own right. PB’s work is not ‘garbage’ but sophisticated, often aurally interesting and beautiful in terms of colour effects. It is, at the core, decorative, like abstract art. Playing it next to really good music is damaging both the concept of music and of sonic art. PB never understood this, because he considered what musicians would call music, also as sonic art but simply of a different, underdeveloped kind (because of being older; read Orientations, Faber & Faber, with his collected essays).

People who are utterly unmusical, don’t experience music but only hear the sound it makes, i.e. they merely hear the sonic surface of it. For them, PB is a composer of music, and that is why so many critics support his misconceived claims. It is much easier to discuss pure sound than musical experience because the latter is so much more subjective and ambiguous.

Boulez’ compositions are all “surface”!

Max Raimi’s great article is both thoughtful and common sense, What a rare combination!

Wonderful, truthful article. Thank you for sharing!

Pity that Pierre can’t reply, how convenient.. As an orchestral musician watching from the audience many times, Boulez transformed my appreciation of how many composers’ sound worlds existed…. He was a musical GIANT amongst, clearly, the bitter and jealous.

Clearly, amongst the bitter and jealous on both sides of the podium.

Mr. Raimi shows that one can play under a composer/conductor — for decades — and still completely misses the point. Proximity/tutelage is no guarantee for understanding.

Boulez’s response to Raimi would be this:

It matters less WHY a particular harmonic structure was used, what is significant in the history of music is THAT a particular harmonic structure was used.

First, yes, anyone with access to a German dictionary can see that Mahler wrote “wild” and any ambitious conservatory student can come up with some pseudo biographical interpretation of what “wild” must have meant for Mahler, and how to play it “wild”. So what? That doesn’t make that interpretation any more authoritative than any other equally valid interpretation of what “wild” means.

Second, and this is Boulez’s point: surely Beethoven had some “wild” emotions to express in his symphonies or late piano sonatas or in Fidelio, yet he never could or would resort to that particular harmonic structure that Mahler used in his 7th.

Third, and this is Boulez’s contribution: there are dozens of recordings that played the “wild” moment appropriately “wild” to the tastes of a lot of people, but Boulez recognizes the harmonic revolution here and makes us hear it, for the first time, for what it really is.

Finally, and this is Boulez’s genius: what is “wild” about that harmonic structure is not the surface savagery with which musicians can play it (and no one doubts the mighty Chicago can play it loud and scary), but it is the very harmony that is “wild”.

Another specimen for my amusing collection of demonstrations that progressive utopianism in music dissolves the critical faculty.

In music, the harmonic combinations, or otherwise formulated: the tonal selections for combinations as part of a structure, are the means to a goal, which is to communicate a musical vision to the listener. The means in themselves are meaningless if there is not also an aim to which they are used. And this vision is something that can be experienced emotionally. Any change in the vocabulary of music is merely result of change of cultural climate, of historical and / or biographical circumstance, or fashion, or convention and the wish to use convention in a personal way. The only thing that matters is whether the work does convey something of a musical experience, and the artistic quality with which that is done. The rest is nonsensical projection.

The only thing more repetitive and tiresome than John Borstlap’s thoughts is his own music:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m-YXULKwDy4

Someone please wake me up when he’s done.

I think Mr. Borstlap’s piece is wonderful. if you don’t like it, then just say that you don’t like it. It’s not like your opinion is worth more than anyone else’s.

I’ve heard numerous pieces of Borstlap’s and though they were all wonderful.

I did, however, find your “thoughts” on the topic to be tiresome.

It’s not your fault that you can only appreciate what is within you intellectual capacity.

Wow, Cherrera, thank-you for letting us all know that just how musically and intellectually superior to all of us you are. I’ll have to remember that when I look on the wall and see my graduate degree in composition, or when I teach a class to my composition or harmony students, or when I’m on stage to a standing ovation after the premiere of one of my works.

Thank-you so much for letting us know that we must look to you to know whether we have worth or not.

That piece was willingly played in a way, clearly not indicated by the score and by the composer. The pianist knew that very well, but choose to ignore the nature of the music, and perform his own, dry and hard version. Some performers think they know better than the author. But of course they are entirely free to expose their lack of understanding what performance means.

In contrast with such attitude, the Dallas Symphony Orchestra just had quite a success this week with some of this composer’s ‘boring music’ under a conductor who not only respects the score and the author, but can profoundly identify with the music, with any music, i.e. a performer at the utter opposite end of mr Boulez – a conductor who has the miraculous capacity to turn a performance of the most worn-out piece of classical music after The Four Seasons: Beethoven V, into the experience of a freshly composed contemporary work.

http://www.dallasobserver.com/arts/review-beethovens-fifth-at-the-dallas-symphony-orchestra-8158521

Classical music: Van Zweden leads another riveting Dallas Symphony concert | Dallas Morning News

Sorry, that link did not quite work. Another try:

http://artsblog.dallasnews.com/2016/03/classical-music.html/

Congrats on the commission and review Mr. Borsltap but music and attitude are still utter garbage.

Do you like this performance of “Avatara” better? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-2YP4AAXzIU (I did.)

To Bruce; yes, that is a better performance, but it is still too ‘active’ and ‘hard’, and the pianist often interrupts the flow of the music when the harmony changes. It’s not very subtle.

I feel compelled to point out that Mahler was not from Bavaria, as the article says.

My bad; I meant to write “Bohemia”. Thanks for the correction.

-Max Raimi

Bravo, Max!

Thank you for confirming the Sanity still has a place at the table!

Terry and Sheila Jones

Sorry to nitpick, Max, but Mahler’s father’s father’s tavern near a barracks was in Iglau, which is neither in Bavaria or Bohemia but in MORAVIA.

A good article, and necessary after the eulogies from many quarters that immediately followed upon PB’s demise. As history will amply demonstrate, PB was a fine conductor but no more of a composer than other fine conductors who put notes down on paper, such as Klemperer, Walter, Furtwangler etc etc etc.

What a great article! First, it demonstrates that the musicians in front of conductors of greatly varied quality have their own thoughts on the music they perform. They are not in need of instruction or tutelage, but a clear musical point of view to execute. This, Boulez provided. What Max Raimi has given us is his own thoughtful and supported point of view of Boulez, and by extension, the state of classical music. The leaders of symphony orchestras would be wise to draw on such resources when making decisions.

I am overcome. I have never dared to hope that within my lifetime, it might be possible to come out of the tonal closet, and survive!

I now have this mash-up vision of an elder Leonard Bernstein impersonating Reagan, standing at a podium and going, “Mr. Boulez: tear down this wall!”

Um, figures such as David Del Tredici came out of the closet (both the tonal one and, in his case, the other one) decades ago.

In fact, he discussed this in the pre-concert talk for his “Child Alice” in Boston just this past Friday:

https://www.bostonglobe.com/arts/music/2016/03/23/boston-modern-orchestra-project-revives-del-tredici-fantastical-child-alice/Xwq0Y2CGq04c84hm8ONqXJ/story.html

http://www.classical-scene.com/2016/03/27/alice-bmop/

I posted a reply to your message. It seems to have disappeared into the ether. I’ll try again.

Tonal composers started coming out of the closet a long time ago. One example is David Del Tredici, one of the founders of the neo-romantic style, who came out of the closet (both the tonal one and the other one) something like forty years ago.

In fact, he discussed all of this and more in the pre-concert talk before the performance of his “Child Alice” in Boston this past Friday:

http://www.classical-scene.com/2016/03/27/alice-bmop/

He also touched on his history with atonal and serial music before he switched to his current tonal style.

Wendy Carlos had a briefer summary of the grim academics who staffed composition schools in the post war period… “They killed music.”

Writing in an idiom rooted in traditional tonality and doing something really good with it, is an art difficult to master, and it has to be handed-down from generation to generation, based upon experience and developing of musical insight and taste. Composers like Strauss, Mahler, Debussy, Ravel, Rachmaninoff, Scriabine, etc. etc. however different they were and however deviating from received wisdom, they had a thorough training in traditional craft, their imagination was rooted in the tonal dynamics shaped by ages of experience. After WW II this continuity was broken and traditional craft deleted from educational curriculae, or merely used as a short, superficial preparation for ‘the real stuff’: modernism. The result is that students who want to relearn some basic compositional craft have to do that as an autodidact. In fact, often conservatories and universities actively discourage any attempt by students to recapture ‘styles from the past’, because the past of the sixties is considered preferable to a past of real musical highlights.

At the Cambridge Music Faculty where I studied in the eighties, students being critical about Schoenberg could face dismissal from the course, and expressing an interest in R. Strauss or Schumann immediately devaluated a student’s credentials. I discovered some fascinating writing in Strauss’ crazy opera ‘Intermezzo’ and that was obviously not appreciated, it was like mentioning Luther in the Vatican. No doubt such biassed education has petrified real creative talent everywhere in the West.

It seems that there remains a refuge in film scoring programs where students are encouraged to explore multiple styles and therefore acquire a wide array of compositional skills. It was my choice to pursue this direction in my own studies. Otherwise, in main stream composition programs it is dissonance and pop minimalism.

Sadly you’re right. And the same thing is true of HIP — and contemporary art in art schools, etc. That’s just the way it is now it seems…

Ironic isn’t it? In a time which claims of itself that a free and pluralistic society, based upon universal values, has finally been realized, there seems to be more conformism around than ever.

What a brilliant article. Absolutely spot on, and thank you Max Raimi for calling it like it is.

It reminds me of taking Kimiko Ishizaka to a famous University so that she could present her first major composition to the head of the composition department there. It was a tonal sonata, with plenty of harmonic and melodic idiosyncrasy that gave it a fingerprint unlike anything I had ever heard. When she had finished playing it, the famous composition professor asked her who her favorite composer was. She answered “Schubert” (this was before her discovery of Bach). He blustered, clearly distressed by the answer, that “you can’t write music like Schubert these days!”

That was always a telling moment to me. The appropriate response would have been “Duh, idiot, nobody can ever write music like Schubert. That’s why he’s so special.” But that would have been talking past the implied point, which was made even clearer by his admonition to go listen to Stockhausen and Crumb. This was clearly a man ensnared by the polemics and Whig history of Boulez.

“In any case, we get the idea. Each piece of music must create its own form according to the material being manipulated; it must owe nothing to anything that exists outside its own microcosm. This unfortunately leaves out a lot of the way the world actually exists in our time.”

This attitude has actually infected education reform here in America at a broader sense. One interpretation of the Common Core standards re: poetry is that the poems are only to be read and interpreted within their own words. There is no specific reason or impetus to actually bring in the historical social context in which these poems actually came into being.

To whit, the Lear metaphor is apt in how English classes are teaching it (if they teach it at all – it is tough stuff for high school kids in the States outside the AP level): the words only matter, not the performance environment that actually drove those words into being written.

To me, that is a rejection of the very essence of aesthetics. It leaves us solely interpreting these words, or these musics, by our over-exposed, under-educated eyes and ears, and leaves us slaves to someone else’s interpretation because we lack the context to develop our own.

So yeah, that it seems to be an aspect of academia that is older than just the current education reform movement here in the States actually scares me a bit.

This article has a lot of problems. For once, this claim should be dead and buried by now:

“For a couple of generations after World War Two, composers who employed elements of traditional tonality became endangered species at the music schools of our great universities.”

Joseph Straus’s work, which takes a hard look at the figures, shows this to be a myth for at least the first generation after World War II. There was so much conventionally tonal music written during that era, and repeating the claim of some kind of atonal hegemony just blinds one to all those great pleasures.

Secondly, the author says that he first worked with Boulez twenty-five years ago. By that time, Boulez had already conducted quite a bit of spectralist repertoire and some of his peers’ turn to a more traditional idiom. He cannot be claimed to have been a continuing believer in the inevitability of atonalism.

As for complaining of Boulez’s treatment of Mahler, Boulez’s reading, while not to this author’s taste, nonetheless filled a niche in the market. Thanks to Boulez, listeners now have one more choice when they want to hear Mahler. How is this a bad thing? And as for portrayals of Shakespearean characters as cold instead of conventionally passionate as traditional performance would have it, that has in fact been done before and has satisfied a demographic of theatregoers.

Finally, to complain about Boulez’s music not being successful with the public is to disrespectfully ignore the existence of people out there who like his music. If some concertgoers really did flee the concert you heard about, blame CSO for targeting their marketing for the concert to the wrong people (I was a patron of the CSO for a few years and repeatedly saw them fail to distinguish their multiple audiences). Me, I go to concerts with Boulez on the program and I like what I hear. It is worth noting that many records of Boulez’s works have sold more than those of various composers who expressly aim to satisfy a mass audience.

But in any event, all of classical music is a tiny niche these days, and a classical musician should be happy to see Boulez’s music reaching its listeners just as the music he enjoys reaches him. Why complain about music one doesn’t like in this day and age of immense choice when everyone can find the music that speaks to him/her?

On the surface of it, all this seems to be very reasonable. But the reality was, and often still is, that certain ideologies dominate production and information of contemporary music. Conventional music histories give an entirely false image of what really happened, and in the educational field there have been grave taboos around questions of tonality, expression, traditionalism etc., taboos which are still in place at many locations where contemporary music is studied and performed. It should not be forgotten that there are different performance cultures: the central performance culture, the contemporary scene, and make-shift, ephemeral attempts to create an improvised podium for new music. These spheres have very different musical paradigms, and they are mostly mutually exclusive. The money and the attention does not go to the modern scene and the periphery, but support the central performance culture where new music is an ongoing, fundamental problem.

This has nothing to do with the availability for the listener of ‘unusual’ music: the listener has the advantage of being served by the recording industry. Performing is quite another matter and the struggle to liberate the central performance culture from idiotic ideas about music, is still not finished.

To demonstrate this situation it may be instructive to point towards Germany, where an excellent central performance culture of classical repertoire exists next to an alternative circuit of new music which is entirely made-up of Klangkunst, i.e. sonic art, with a very different audience. That’s fine – but there is no new tonal or traditionalist music being written in Germany, surrounded as it is by taboos stemming from WW II (a modernist German is a morally good German.) Also Austria is still suffering from modernitis, their composers being either lighthearted, nihilistic eclecticists (Cerha) or fanatic feminists (Neuwirth). The young Austrian newcomer Johanna Doderer leaves all that behind, which is a hopeful sign, and the older but very interesting Wolfram Wagner (no family) who revives the fertile twenties, is an exception in Vienna. In France, younger generations try to restore prewar French music with lively and expressive music: Bacri, Beffa, Connesson, Dubugnon. But when pianist and composer Jerome Ducros – invited by Karol Beffa – held a lecture at the Institute de France, critically treating french modernism with irony, he unintentionally set a widely-published scandal in motion including ‘politburo’ actions in which Boulez played a despiccable role:

http://subterraneanreview.blogspot.nl/2016/01/jerome-ducros-modern-anti-modernist.html

Audiences are not aware what kind of cultural warfare has been going-on, is still going-on, behind the screens. Classical music is not the quiet realm many people assume it is.

At the very end of your post, you ask why we might complain that the music of Boulez (and the like) is being offered amidst a huge array of musical choices for the audience.

This “huge array” is actually getting squashed where I live. The NY Times critics have decided that for any music organization to be approved, they must avoid playing masterworks that I would like to hear, and take chances with modern garbage in every single outing (let’s say there is a 5% chance that I will remotely enjoy the piece, and a .002% chance I would ever want to hear it again. I really do have the experience to make those estimates).

So the conventional programs just don’t exist around here any more. I’ll listen to my stereo at home. Maybe I’ll even listen to Beyonce and Mariah Carey. At least their music uses harmonies that speak to me.

There is much pre-modern music which is appealing and interesting that is never or hardly ever played, not because it is not good but because it takes a bit of effort to find performers who want to play it, most performers share the routine paradigm of a restricted repertoire that everybody is supposed to know so that all attention goes to the performance. How often do we hear Cesar Franck’s ‘Chasseur Maudit’, a brilliant symphonic poem, or his Variations Symphoniques for piano and orchestra (a master piece)? Or Fauré’s Ballade for piano and orchestra? When can we enjoy a life performance of Berlioz’ Chasse Royale from Les Troyens, or Dvorak’s violin concerto? Where are all those engaging Haydn symphonies? Not to speak of early 20C works like Debussy’s Jeux (very hard to play but if well played, a spectacular experience), Stravinsky’s piano concerto with winds, Poulenc’s concerto for organ, string and timpani. Or – a rarety but fascinating piece – the cello concerto of Ernst Toch? Just a couple of brilliant, engaging, fascinating works, but they fall out of the routine programming and would need some extra effort in terms of marketing, which will cost money, so there are many reasons to not program them and they are all wrong. And then we not even talk about contemporary music, let alone the sonic art of PB and friends.

Or the works of Martinů? A few years ago I heard the Symphony No. 6, Fantaisies symphonique, performed by the American Symphony Orchestra, Leon Botstein conducting. The performance was finely realized, a refreshing experience because of the relative unfamiliarity of the score. This is the sort of accessible music that wouldn’t see to be so alienating to the general audience for classical music. But how often is Martinů programmed in the United States?

Also on the program were Schnittke Symphony No. 5 and two works by Grażyna Bacewicz, so this was a rich program of music by notable twentieth-century composers. The venue, Alice Tully Hall, was not nearly filled.

If such a concert cannot fill 1,100 seats in New York City, what hope is there for the future of more-or-less modern music?

Composers have long derided other composers for being on the wrong bus. I don’t like it, but it’s certainly not unique to Boulez. Yes, in his youth his statements were extreme and obnoxious. That’s all too common. I’m not saying this to forgive nasty comments, but to point out that nastiness about musical style has been pervasive. Even here, in the comments, you can see people claiming that their own taste or aesthetic framework is self-evident and superior to other mistaken or destructive ideas.

The difficult truth is that human beings do not agree about what is beautiful. They don’t agree about what kind of music is worth making or worth listening to. They have different agendas, different tastes, and different convictions about music’s essential purpose and true nature. Some people don’t like music that other people love. And powerful musicians deny opportunities for music they don’t like, and say demeaning things about music that doesn’t fit their agenda. The talk around classical music makes it seem that there is consensus about what is good music, but there isn’t.

Meanwhile, s far as I can tell, the war between serialists and everybody else is over; everybody else won. As Max Raimi points out, the non-dead composers getting played these days are doing other kinds of things. But we are left with arguments about what kind of music should be played. These arguments seem to me unfortunate and too often simplistic. For myself, I want to hear wonderful musicians of diverse points of view make the musics that they find compelling, meaningful, soulful. I know I’m not going to like all of it, but I love the endeavor. I know that this means that some institutions will focus on music I don’t care for. That’s fine with me, as long as the ecosystem is diverse.

Susan McClary wrote a wonderful article about the hegemony of postwar modernism. It’s called “Terminal Prestige.” I found it tremendously helpful in understanding why serialism became the dominant approach, even though audiences didn’t like it. https://edwardsmaldone.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2011/01/Terminal-Prestige-the-Case-of-Avant-Garde-Music-Composition.pdf

Finally, many thanks to Max Raimi for putting his experience into words so eloquently. I think it’s wonderful to hear from orchestral musicians about the music and musicians with whom they have such intimate contact.

One of the best replies yet =)

Agreed. Artists commonly define themselves in opposition to other artists. I think it was Poulenc who wrote that the greater the artist, the more dogmatic. He went on (modestly and charmingly) to say that his own broad tastes probably reflected the fact that he was a minor composer. A challenge: name five great composers who didn’t dismiss other great composers as being beyond the pale.

Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms.

Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, I believe?

Although Tchaikovsky reportedly dismissed Brahms as “a mediocrity [!] with a small heart”.

Thank you for your gentle and eloquent commentary.

BTW, I have read and performed some of your music — alas, without goldfish.

Alright, so there are basically two take-aways here, one major, one minor:

1. Boulez is now what Wagner was to Virgil Thomson* – a representative of the old regime, whose greatness the new regime is obsessed with diminishing, partly because they know their advantage is temporary; partly because, as long as they keep fighting the old battles, they can keep pretending they’re still rebels. (Corollary: Shostakovich is now the establishment.)

* Right down to the nitpicking of their interpretations: Of course Boulez remade Debussy and Mahler is his own image (partly, I suspect, to cover up his greater debts to Stravinsky and Messiaen, in the first case; and to cover up the Second Viennese School’s greater debt to the embarrassing Richard Strauss, in the second), just as Wagner remade Beethoven in his (come to think of it, partly to cover up HIS debt to Berlioz). So what?

2. Guy Raimi hasn’t read Hannah Arendt. “[A] crushingly vulgar fortissimo waltz theme grotesquely orchestrated with an appallingly banal accompaniment…” supposedly evocative of “drunken, brawling soldiers” – this fear of the uncouth lower orders has nothing to do with the banality of evil. The banality of evil would be evoked by music as thoroughly superficially respectable as Eichmann was himself – in Mahler’s time, maybe a tasteful reminisce of Johann Strauss, Jr.; in ours, maybe Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald Sing the Gershwin Songbook. (Respectable popular music generally means whatever was un-respectable several generations previously.)

I think you confuse “banality” and “banality of evil”. What exactly does a banal accompaniment have to do with Hannah Arendt?

You’re confusing what Raimi wrote with my commentary on it.

Claiming that Mr. Raimi wouldn’t have read Hannah Arendt (BTW, how do you know?) could have only any relevance in this context if Gustav Mahler would have read her before the composition. As it is, it seems to be a rather absurd statement.

So… did you just not get to the end of Raimi’s sentence?

Evidently you’re missing the part where Raimi cluelessly asserted that the banality of evil is evoked by Mahler’s “crushingly vulgar fortissimo waltz theme” – which of course my reply was written to address. Seriously, did you idiots all just skip to the comment section without even reading the piece under discussion?

Also you’re evidently dumb enough to approvingly quote George Orwell.

So in other words you deny being an idiot. But how, exactly, are you not an idiot here?

Just admit you didn’t read the piece already. (You’ll feel better!)

In Canada, CBC Radio 2 homage to Boulez lasted 38 seconds…

(…) Unable and unwilling to present a critical appraisal of his work, it is indeed ironic that CBC producers/bloggers would join the correctness chorus of fervent praise lavished on Boulez on one hand, just for them, when it counts -that is broadcasting HIS music to the masses-, choose to only present Boulez the conductor on the other: Le Marteau Sans Maître ends up being worthy of a link in a blog but not of a nationwide broadcast, despite proclaiming the death of a genius…(…)”

http://pianistsveta.blogspot.ca/2016/02/of-boulez-bowie-and-cbc-radio-2.html

This is all pathetically amusing… all these insights .. reminds one of the story of

the blind men and the elephant ….

One can easily imagine which part of the elephant you got.

I bet you can ……

You win. He’s read your commentary before.

“I first played under the baton of Pierre Boulez more than a quarter of a century ago”

I don’t recall ever seeing PB with a baton. Nit picking aside, IMHO the CSO always played superbly for him. We first heard him conduct the Ravel left-hand bit. The tension in the opening pages was palpable and when the piano came in, you wanted to finally relax and have a cigarette.

Surely this essay is mostly about his composition side. I bet 90% of commenters would agree his was a towering figure as a conductor. We just want his silly and uninteresting compositions to be forgotten for good.

Why should music that gives great pleasure to a certain niche of listeners (such as myself) ‘be forgotten for good’? Seems rather rude that you would want that. You probably enjoy a great deal of music that I don’t care for, but I’d never hope that that music would vanish. Do you really think the world would be a better place with less for listeners to choose from?

Often in life, having too many choices leads to bad choices.

You seem to be a gentle person so I am sorry in advance I don’t have a short answer for you. But Boulez didn’t just take the spot that is his. He monopolized the music scene. That’s why I curse him.

So because you consider Boulez to have been a bad man, those who enjoy his music must lose something that enriches their lives? Boulez can’t hear your curses, he is dead and gone. The only people you are talking to now are your fellow classical music listeners, and some of them like Boulez’s music. Live and let live. As I said, I don’t disparage the music you like.

Spot on.

If you actually knew anything about Boulez’s music except that you vaguely feel it shouldn’t exist, you’d know he didn’t even monopolize the avant-garde music scene for long. In 1958 he was dethroned by Stockhausen.

That aside: it’s not Boulez’s fault that he was more talented than Jérôme Ducros and John Borstlap.

It’s not even his fault that Éliane Radigue and Gérard Grisey and La Monte Young and Steve Reich were also more talented than Jérôme Ducros and John Borstlap.

It’s not even his fault that Caroline Marçot and John Luther Adams are also more talented than Jérôme Ducros and John Borstlap.

Before very long, when the dust has settled and his celebrity abated, they will be.

“I don’t recall ever seeing PB with a baton.” I once saw Boulez, when asked why he didn’t use a baton, wave his fingers, give his entirely charming Gallic laugh, and say “Actually, I use ten of them!” So perhaps I should have written “I first played under Boulez’s BATONS more than a quarter of a century ago.”

So, in a nutshell…

Pierre Boulez doesn’t like Shostakovich -and explains why- and that makes him a totalitarian. A third-rate “composer” wets himself every time he sees the name “Boulez”, writes that Derrida, Foucault and Baudrillard “suffered from some affliction in the brain”, calls Friedrich Cerha “nihilistic eclecticist” and Olga Neuwirth “fanatic feminist” and that’s OK… And let’s not forget his infamous comments on David Bowie, on jazz music and on modern architecture…

Wow… Just wow…

We knew that this Bortslap was an arrogant egomaniac with a superiority complex with a tendency toward trolling… Now we know that he’s also hypocrite, intellectually dishonest and… totalitarian!

Yes… I know… it’s all very difficult, isn’t it? It would be so much more convenient, in music life, if everybody just simply embraced received wisdom and stopped thinking and observing independently, and adapted generally accepted views, and avoided debate. But seriously, if people were better informed about the mores in the field of contemporary music, which are not widely published, independent opinions would not seem so crazy any longer.

I would discretely advise to begin with Alex Ross: “The Rest is Noise”. This gives an impression of the cultural warfare which has been going-on since Schoenberg got the idea that there was progress in music. PB choose to be a warrier, and together with a whole generation of postwar revolutionaries, set-out to destroy musical tradition. It’s there where all those silly superlatives of the comment can be found.

At its roots, I sense this is really a debate between modernism and post-modernism. Boulez was an uncompromising modernist, believing in historical progress, whereas the author of this article is more of a populist post-modernist for whom there is not so much progress as difference and variety, in music and other fields. That explains his complaint that Boulez was, in a sense, old fashioned and elitist.

Many of his criticisms of Boulezian dogmatic modernism, it seems to me, hit the mark, at least partially, but he neglects, I think, to point out the weaknesses of the post-modern position. Polystylism can end up stuck in a circular rut of parody and repetition. Also, note the contradiction. The article regards Boulez as being ‘left behind’, yet the very term is itself indebted to a modernist outlook. As a concept, modernism seems to be a boomerang that is difficult to throw away.

Yes, I like Shostakovich, but I am not so confident as to dismiss Boulez, and modernism, so swiftly.

More than a grain of truth in this comment. But from a postmodern perspective, it can be concluded that modernism was merely a phase in music history, from which we are liberated simply by the passing of time. Postmodernism can never be a fruitful aesthetic position because there are no standards against which things can be measured, there is no quality framework, no historic perspective. The reality of today’s cutlural situation is a pluralism where everything exists next to each other (which is fine), and at the core this is a static situation, which was already predicted in the sixties by Leonard B. Meyer. Within such a pluralistic field, people / composers can choose what they like. Where their interests draw them to the best, inevitably they are drawn towards tradition, it seems to me, because there, value frameworks still operate as they did in the past. (This, by the way, probably explains audience’s preferences of older repertoire.) So, postmodernism as a philosophical outlook can open the way to a new look upon value frameworks and I understood Raimi’s excellent article in that way.

ERIC SHANES wrote that “As history will amply demonstrate, PB was a fine conductor but no more of a composer than other fine conductors who put notes down on paper,”

Ask any of the thousands of choristers in the UK who were fortunate enough to have been conducted by PB and they’ll all tell you that he was wonderful, Ask any of them what they thought of his own music and they’ll look uncomfortable and then change the subject. There remains a deal of truth in the alleged origin of the expression “The old grey whistle test.” and only time will reveal the truth of it. Like the ‘alleged’ response of a professor of Composition to an overenthusiastic first years student’s anxiety to know what the teacher thought of his work. “Your compositions, young man, will be remembered when those of Bach and Beethoven are forgotten – and not before.”

That’s just nasty. How does the professor know that this student would not develop in a spectacular way? When Beethoven was a young, upcoming pianist who also composed between performances, once on an after-concert-party he expressed to an elderly musician the need to find a publisher for his work, upon which the other said: ‘Well well young man, finding a publisher is only something really great composers can hope for, like Haydn’. As a student, Ravel competed vainly for the Prix de Rome, while already having written his string quartet, but he was found wanting in compositional quality. Etc. etc….

You have to realise that all of these prizes are awarded with political intent. Quality, merit and worthiness only qualify the candidate for entry not for success, Look at Berlioz and his yearly attempts at the Prix de Rome. There remains a hard core of music lovers and musicians [who are in all probabilities making every effort to avoid performing or attending performances of all atonal music] who will be around when this ‘phase’ has taken its place in the scales of worthiness. Having had the pleasure and privilege of having sung for PB but also the dubious privilege of listening to his compositions, I remain firmly in that latter camp. The entire spectrum of atonal music is for me a closed book which I am in no hurry to open. Not all of us are ‘worthy’ to ‘comprehend’ this version of musical form and set against 60+years of enthusiastic and reasonably competent performance of the earlier 300 years-worth of music, I sit comfortably in that company of musicians which can comfortably manage without Stockhausen, Birtwhistle and Ligeti – the last of whose music I have performed, albeit with little pleasure.

Well, that shows that you are a musician and not a sonic fan, and can make some important distinctions. I think that the point is not to listen to or to perform sonic art with the idea of music in mind….. in fact, it is not meant for musicians, and many performers who are so enthusiastic about sonic art appear to be quite unmusical in the field of music, in the sense of: not understanding how music ‘works’, which appears from their attempts to perform it. I know of quite some brilliant performers of postwar modernism, either as soloists or as members of specialized ensembles, who failed when tackling some work of the musical repertoire. And when some really good performers (of music) try their hand(s) on sonic art, they attempt to put something into it that is not required (Barenboim and Honeck with PB’s works). When a musician tries to explain to me the reason why he/she gets wild about, say, Xenakis, that immediately rings an alarm bell as to that person’s musicality. In most cases, such suspicion is confirmed later-on.

Which does not mean that serious musicians genuinely have tried to defend atonal modernism, sometimes in spite of their own instincts. A concert master of the Berlin Phil who also was a soloist, once told me that when he played the Schoenberg Violin Concerto, he had to make a strong effort to forget – i.e. ban from his mind and emotional receptive apparatus – all music from before Schoenberg, and when he had to do the Mendelssohn or Tchaikovsky after the Schoenberg, he had again to cross some inner barrier, but then into the other direction: trying to forget the sound world of Schoenberg and that idiom of harsh dissonance. He never understood why, but the answer is obvious.

Very good point ! I have never understood why atonality was the holly grail of modernity in music. For me, Shostakovich is far more representative of the XX th century with all it’s tragedies than Mr Boulez et concorts.

And now composers use some form of tonality and melodies again because that’s what people want. They have to reconnect the public whith modern music !

“And now composers use some form of tonality and melodies again”

Actually, they never stopped. There is so much tonal music from the 20th century to explore, and atonality was just its own niche. If you think that tonality and melodies disappeared, you are probably blinding yourself to myriad pleasures, and that would be a real shame.

“because that’s what people want.”

Am I and other Boulez listeners not people? Some of your fellow human beings would like more of the particular style that Boulez explored.

“They have to reconnect the public with modern music!”

Boulez and his avant-garde peers did a pretty good job of connecting me with modern music. I knew absolutely nothing at all about classical music before a chance encounter with some mid-20th-century modernist recordings knocked my socks off. I immediately liked what I heard. Indeed, if I can now enjoy the Romantic and Classical eras, it is only after working backwards from the avant-garde.

I remember hearing Ned Rorem, a Boulez contemporary who had lived in France for a long while, say on American television in the 70s that ‘the USSR had Stalin, Germany had Hitler,

now France has Pierre Boulez.’ Ach, du holde Kunst.

The one and only thing the unreconstructed Modernists and equally unreconstructed Anti-Modernists can agree on: the other side is Hitler.

What would ‘reconstructed’ modernists and anti-modernists be?