Dame Kiri: Nuns beat me

mainThe dowager dame has been telling kids back home that she was beaten by brides of Christ – and it toughened her up.

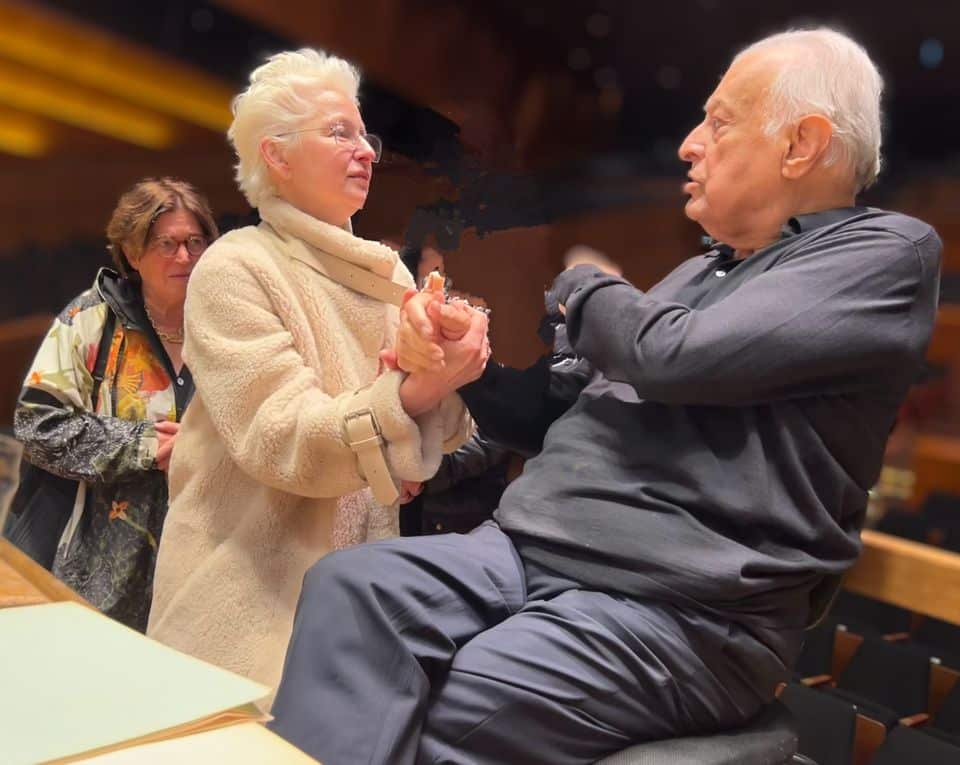

The opera star stunned a Whanganui audience with the revelation during a speaking event with opera singer and Baptist Church minister, Rodney McCann, the Whanganui Chronicle reported.

“I am as tough as I am today because from age 12, when I was at a convent school in Auckland, I was beaten by the nuns,” she told a crowd of several hundred fans.

Not sure what her message is here. Tick one of the boxes below:

Children need to be whipped

Masochism is underrated

Opera is not all beauty

I should have gone to church more

I should never have gone to that school

You kids are so soft today. We used to get whipped before breakfast, forced to play nude rugby all morning, no lunch, arpeggios all afternoon, hakas at tea and cold showers before bed. That’s how I got where I am.

Comments