Gidon Kremer picks the best-ever Beethoven concerto

mainAt least that’s what he was asked to do by the French magazine, Diapason.

But for Gidon there is no such thing as best and no acceptance of the record industry’s repeated claims of perfection.

So he proceeds by way of Oscar Wilde and Mieczyslaw Weinberg, Lockenhaus and Leonard Cohen, to give a tour d’horizons of what goes on in an artist’s mind when preparing and considering an interpretation of great music.

He has sent us the English original of the article, which runs to 44 fact and anecdote filled pages.

Here’s the longlist he compiled.

1 Joseph Szigeti / Bruno Walter / British Symphony Orchestra, 1932

2 Bronislaw Huberman / George Szell / Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, 1934

3 Fritz Kreisler / John Barbirolli / London Philharmonic Orchestra, 1936

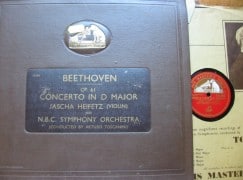

4 Jascha Heifetz / Arturo Toscanini / NBC Symphony Orchestra, 1940

5 Yehudi Menuhin / Furtwängler / Berlin Philharmonic, 1947

6 Christian Ferras / Karl Böhm / Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, 1951

7 Zino Francescatti / Dimitri Mitropoulos / New York Philharmonic, 1955 (live)

8 Nathan Milstein / William Steinberg / Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, 1955

9 Jascha Heifetz / Charles Munch / Boston Symphony Orchestra, 1955

10 Leonid Kogan / Constantin Silvestri / Paris Conservatoire Orchestra, 1959

We will not reprint the whole essay – you can read it here. Nor will we give away Gidon’s final choice of his favourite recording of the Beethoven violin concerto. You may be in for a surprise. A shock, even.

But here are a couple of excerpts to whet the appetite until you curl up with the full article this weekend.

A concerto should be a “conversation” and in no way a “competition” between a soloist and an orchestra that is controlled and led by a conductor – a genuine demonstration of concertare. It must be clear that in a major work such as Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, the protagonists should be equally important. What then becomes interesting for a listener (as well as for all participating musicians) is how (on what terms) the expected “conversation” takes place. An ideal performance should provide space for all participants to feel part of the presentation.

We can be sure that if a conductor were to decide that he were more important than the soloist, it would be considered an affront and an indication of profound disrespect for all the work by Gidon Kremer, Searching for Ludwig 8 the soloist to read the dots and strokes left by the genius creator (occasionally meaning months or even years of work to master the extremely difficult solo part).

In my own experience of having played a large variety of works, I have also seen “disrespect” assuming a different guise. Nowadays (although I wonder if it really was different in the past), some conductors – even some truly gifted ones – have no compunction about turning up at the first rehearsal shamelessly underprepared. It is as if the ability to “manage” rehearsals efficiently and quickly, not to mention the following concerts, takes precedence over matters of artistry.

I recently witnessed an artist (who is best left unnamed) literally sight-reading Alban Berg’s mysterious violin concerto – with absolute ease … but zero meaning. Cases like that reinforce the necessity of establishing a “pact” for a harmonious reading of any great score. In the selected recordings of Beethoven’s masterpiece, I had to consider relationships between famous “names” such as Menuhin and Furtwängler, Szigeti and Walter, Kreisler and Barbirolli, Ferras and Böhm, Francescatti and Mitropoulos.

*

It has been one of my life’s privileges to have played with many wonderful partners (some of them conductors, such as Herbert von Karajan, Leonard Bernstein, Carlo Maria Giulini and Nikolaus Harnoncourt). I learned to distinguish between those who spoke “my language” (or let’s be more modest, “whose language I tried – while I was still ‘learning the ropes’ – to understand and speak”) and those who, for all their greatness or mastery, remained “estranged” from me.

They included some of the members of the “Premier League” (Lorin Maazel, Claudio Abbado and Pierre Boulez, for example) – and possibly the feeling was sometimes mutual! My search for the most genuine and intense dialogue became one of the parameters of my comparison. I wanted to find a recording that would demonstrate an ideal “partnership”. Did I actually need to look further – wasn’t it bound to be Heifetz and Toscanini?

*

I recalled how, when I was a student, David Oistrakh reflected on my rendering of the very romantic “Poème” by Ernest Chausson. I was seriously in love for the first time and indulging my emotions. My teacher interrupted me soberly with a comment on my glissandi. “Gidon, you can’t use so many slides – that’s how violinists played 30 years ago.” Somehow, though, many youngsters still seem to feel that they have to fill in shifts between notes and that greater effect is produced by introducing slides. I am tempted to comment, “80 years too late.”

Interestingly, in his study of even more archive recordings of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, Professor Mark Katz also observes that less use is generally made of glissandi these days; the emphasis is more on letting music “speak for itself”.11 Now that’s a point I agree with! But what does it really mean in connection with Beethoven’s concerto?

To sum it up – times have changed. Bearing in mind that the late twentieth century accentuated the absolute need to focus on published manuscripts, what was permissible (or even “in”!) some decades ago has left us with many examples of glissandi – albeit employed with sincerity, great authority and full technical command – which have turned out to be slightly … wrong.

Comments