World’s oldest cello goes on show in New York

mainThe Amati “King” cello, the earliest of its kind, will go on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art from June 11.

It is on special loan to the Met from the National Music Museum in Vermillion, South Dakota.

press release:

Location: The André Mertens Galleries for Musical Instruments, Gallery 684

Dates: June 11—September 8, 2015

(New York, June 8, 2015)—The Amati “King” cello, one of the world’s most renowned musical instruments and the earliest surviving bass instrument of the violin family, will be on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art beginning June 11. Built in the mid-16th century by Andrea Amati (ca. 1505-1577), the founding master of the great violin-making tradition in Cremona, Italy, it is on special loan to the Met from the National Music Museum in Vermillion, South Dakota.

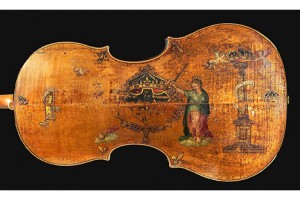

The “King” cello’s name refers to its royal commissioning. One of a set of 38 stringed instruments made for the Valois court, it is painted and gilded with the royal emblems and mottoes of King Charles IX of France (d. 1574), son of Catherine de’ Medici. Gilded letters spell the word “PIETATE” (“piety”) on the bass side and “IVSTICIA” (“justice”) on the treble side of the instrument. The letter “K” in the center rib signifies “Karolus,” or Charles IX.

At the Metropolitan Museum, the cello is the centerpiece of an installation that honors the innovative craftsmanship of Andrea Amati, his sons, and grandsons, who directly influenced the work of Antonio Stradivari and other renowned stringed-instrument makers. On view with the “King” cello are two additional instruments by Andrea Amati: an early viola on loan from the Sau-Wing Lam Collection and a violin from ca. 1560 from the Met’s collection. The gallery also features instruments created by Amati’s son and grandson, members of the Guarneri family, and Antonio Stradivari.

What a shame that this instrument has been altered (read: butchered), cut down to dimensions deemed suitable for modern cellists. Of course, that is the fate of most stringed instruments from the 16th-18th centuries, so this one is hardly an exception.

I am in hearty agreement with James of Thames. I recall a conversation years ago on the occasion of the purchase by a wealthy local doyenne of a Stradivarius violin. The instrument was to be donated for perpetual use by the concertmaster of our city’s symphony. I asked the group how they thought the buyer might react if she knew that the Stradivarius was not in its original condition. Another fellow said, “Not to worry, she’s not in her original condition either.”

What a shame also that the museum in Vermillion (with few, if any, exceptions) does not allow instruments in their possession to be performed. Such a stark contrast to the Library of Congress, which is so generous in allowing performers use of their marvelous instruments.

I dare say, had the Amati ‘King’ been played continually since it’s birth amost 500 years ago, we would not have it with us today to study and revere. (What about it’s 16th-cen paintings? I supposed they’ll be manhandled too?) It is arrogant for one generation to assert such a demand on an historic object with little thought for future generations who might wish to marvel in this priceless object from the court of Catherine of Medici’s son (Philip IX of France). The NMM in Vermillion also preserves the ‘Harrison’ Strad violin and several other almost completely unaltered stringed instruments. The ‘rare’ instruments in performers hands today are almost invariably a mere shadow of their original selves, due to later alterations, revisions, and repairs necessitated by their use in performance. The mission of museums such as the NMM is to preserve material culture for the indefinite future and to “do no harm.”