Nobel Prize winner: Here’s what science can learn from musicians

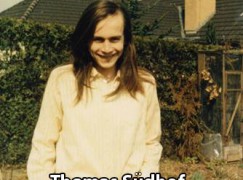

mainWhen Thomas Südhof won the 2013 Nobel Prize for medicine/physiology, he gave credit to his music teacher for the important advances he had made in discovering ‘ vesicle traffic, a major transport system in our cells.’

He spoke again soon after, in a conversation with the editor of a bassoon magazine, underlining the value of the discipline he had acquired from immersion in music, while lamenting that classical music in the US is ‘fundamentally a dying art.’

Now, for the first time, Dr Südhof has spoken about the specifics of his musical training and its relation to scientific practice. In an exclusive interview with Stuart Diamond of Empowered Doctor, he emphasises the importance of one-on-one teaching and the importance of ‘hard, unimaginative, non-creative, repetitive work.’

Here’s what he says, with a linking paragraph by Dr Diamond:

DR. SÜDHOF: First, I was exposed to playing music in school, the recorder. Then I began the violin. I wasn’t very good at it. I didn’t like the teacher. Perhaps it was the age, possibly the instrument. So I stopped playing the violin on my own initiative. But after a while, I decided I needed to do some music. So I picked the bassoon. I have no idea why. It may have been after all the subtle hints of some of my teachers. I doubt it was my parents. It may have been that I liked those sonorous deep sounds.

In my own experience playing bassoon puts you in immediate demand. You are courted by any number of ensembles, whether or not you could actually play adequately. But that was not the case with the young Thomas. When he first started to play where he grew up in Germany, there was no youth-training orchestra. So he simply took lessons and played on his own. As he grew older he became more accomplished and played in the State Youth Orchestra and traveled with the group throughout Europe. He considered the possibility of pursuing a career as a professional musician. Though acknowledging how satisfying a career as professional musician could be, he was also well aware of the hard realities of life as an artist. I then asked him exactly what he meant when he said his bassoon teacher was his most important teacher. Did he really mean that?

DR. SÜDHOF: Yes I do. I think, that in general, teaching is extremely dependent on personal relationships. It is important that one has teachers, who you can personally respect – a whole persona you can see. It is true in science as well in music, as well as other aspects of life. My bassoon teacher was the typical German musician that went through the system, learned how to be a bassoonist, and became an orchestra bassoonist in Hanover. He taught me from day one. I only had one teacher ever. He wasn’t set though on turning me into a professional musician. But he was set on having a certain degree of quality instilled in me. What I mean, when I say he was my most important teacher is that I see playing music very much akin to many of the other things I do. In that playing music requires above all a lot of practice and hard work. Creativity is not just imagining stuff. You can’t be creative if you have no mastery of the medium. Some people master the medium, but are never creative. So it’s not like you master the medium and you are automatically creative. But if you don’t master the medium you will never be creative. You will never be good. That relates to what I do as a scientist. It also relates to what doctors do, in that you can’t be good at it, unless you are really technically outstanding. And to become outstanding takes just a lot of hard unimaginative, non-creative, repetitive work. That is most of what we do. And that is the absolute prerequisite. In that sense it is the same as in music.

Read the full, fascinating interview here.

Comments