Two maestros in America gave me all the time in the world

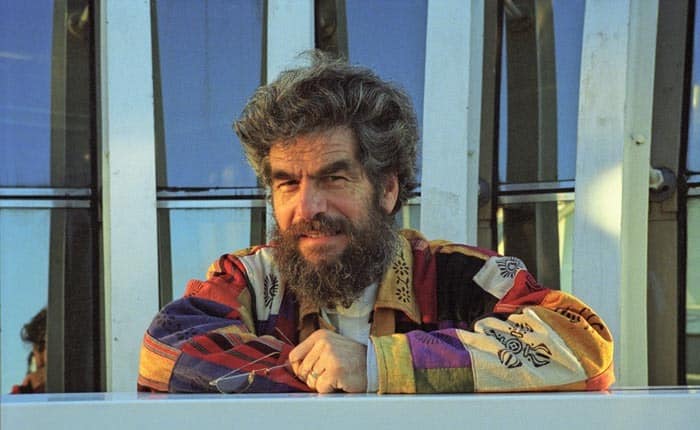

mainJonathan Berman, 27, a youg British conductor, won a Kempinski Arts Programme Fellowship to work for six weeks with franz Welser-Möst and Michael Tilson Thomas. Here’s his account of the experience.

I arrived in Detroit in the middle of a Polar Vortex with temperatures of -21°C . My onward flight to Cleveland was cancelled necessitating a 6hr (instead of the usual 2hr) taxi ride with the door held shut by seatbelts due to the cold. Eventually we got to Cleveland and having slept and cleaned up I arrived at Severance Hall on time, to begin a six week long Kempinski Arts Programme Fellowship.

I began putting a personalised program together with Marylea van Daalen back in October. In the Kempinski Foundation I was amazed to find an organisation which truly cared about the needs of the recipient. We came up with a program which comprised spending January with Franz Welser-Möst and the Cleveland Orchestra, beginning in Cleveland and then following them on tour to Miami. I would then stay in Miami with Michael Tilson Thomas and the New World Symphony until mid-February. This would give me the opportunity to see two conductors and orchestras with very different missions and aesthetics, but both at the very top of the music world.

The Cleveland Orchestra has a tradition spanning over 100 years with music in the city going back even further (Schubert’s Nephew set up a brass band in Cleveland in the 19thCentury!). Historically the orchestra brings together performance traditions from America and Europe. Former chief conductor George Szell stated that the orchestra’s aim was “to combine the American purity and beauty of sound and their virtuosity of execution with a European sense of tradition, warmth of expression and sense of style”, a statement that remains as true today as it was 50 years ago.

The Cleveland Orchestra rehearse and perform concerts in Severance Hall which was built in 1931 and has one of the great Art Deco interiors. Recently restored and modified the building is spectacular; from the Grand Foyer with its Egyptian murals to the Chamber Music Hall with its feel of an 18th Century drawing room. This is the orchestra’s home, and its acoustics have evolved symbiotically with the sound of the orchestra. Now with a reverb time of 1.8 seconds the hall has a beautifully clear, but warm sound. Everything can be heard, even the softest pianissimo in which this orchestra specialises.

Somehow Cleveland presents itself as a community orchestra who personally know the members of their audience. Before and after concerts the players welcome and talk to their friends, students or colleagues naturally breaking down the barrier between stage and audience. However, when playing it is a different story. This is a world-class ensemble made up of an astonishingly good rostrum of players. Hearing the players warm up you hear the level of finesse and fitness of each individual member, and as a group the players exude a deep pride in their playing combined with humility and friendliness to the public.

I had, in the past, attended a number of Franz Welser-Möst ’s concerts in London with the Vienna Philharmonic, knew his recordings, and I had seen a video of him rehearsing Mozart with the Cleveland Orchestra. Mozart is so often under rehearsed, however in this video Welser-Möst rehearsed with such care and in such detail, that I had for some time wanted to meet and watch his rehearsals. Winning a Kempinski Fellowship made it possible for me to see him first hand –he didn’t disappoint at all!

During my time with the Cleveland Orchestra, Welser-Möst rehearsed and performed music from the Central-European tradition (Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, J. Strauss, R. Strauss and Korngold). However they also worked on repertoire further afield (Stravinsky, Debussy and even a 30 minute tone poem by Jorg Widmann, a young Austrian composer). Welser-Möst rehearsed all of the repertoire equally, and with great care. His approach came directly from the score, and the detail of what is actually written. However he didn’t confine himself to the words written instructions, but based his interpretations on the actual notes, harmonies and underlying structures in the music.

In Cleveland Welser-Möst’s rehearsals on Mozart were a master class in how to change small details, like articulation and dynamics, to dramatically affect the character of the music and change the architecture of a performance. In all Welser-Möst’s music making there was an underlying ideal, which he expressed so concisely in a pre-concert talk when he said of Johann Strauss, “lightness is not the opposite of seriousness”. This idea manifested itself in all of the repertoire I saw him conduct; even in Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring he managed in places to create light clean textures without sacrificing any of the drama.

On a personal note, his week of all Brahms (Symphonies 2 and 4, the Violin concerto and both the Tragic, and Academic Overtures) was particularly interesting. For me Brahms is somehow a kernel at the centre of music. He combines seemingly opposite compositional tools: Counterpoint and Harmony, emotional content and structural development, or most simply, deep personal choices with flawless academic construction. I was able to see how deep Welser-Möst’s decision making and rehearsal went and thus challenge my own ideas. He managed to find a balance between keeping the lightness, flow and humour of Brahms’ writing, whilst still giving weight and time for the details of the score, allowing the underlying structures to come out in such delicate and subtle ways that it showed me the crudeness of my own ideas.

Welser-Möst was kind enough to give me some personal time during which we spoke at length about the craftsmanship needed as a conductor. He sees the craft of conducting as having a direct relationship with the operatic repertoire. In particular he spoke of the difficulty of performing Puccini and of how having to deal with the inevitable changes that happen night to night in opera is the best training for the flexibility you need as a conductor. Possibly most interesting when speaking to him was a conversation about literature, and in particular his recommendation of the plays of Alfred Schnitzler as being the clearest example of Viennese aesthetics and atmosphere.

The temperature difference between Cleveland and Miami (over 40°C) was reflected in the cultural, even linguistic differences. The New World Symphony, in comparison to The Cleveland Orchestra, is in every way a ‘New’ orchestra. Based in South Beach Miami in a brand new Frank Gehry concert hall the orchestra is made of ‘Fellows’ who are recent graduates from the top Conservatories. They spend up to three years living in the New World Symphony’s specialised accommodation walking distance from the concert hall. The program is made up of orchestral and chamber music concerts, master classes and coaching from an abundance of top professionals. Everything about the organisation tries to explore new formats and develop the next generation of concert makers.

The New World Centre, designed by Frank Gehry is a curvaceous asymmetrical building where the Miami sun streams through great panes creating always-changing shadows on the bright white interior. The concert hall has a fully flexible stage to accommodate everything from recitals to symphony concerts. The whole building is filled with top of the range video, audio, and projection equipment even including a permanent outdoor cinema in the park in front of the concert hall where concerts are regularly projected onto the wall of the Centre for anybody to come and watch for free.

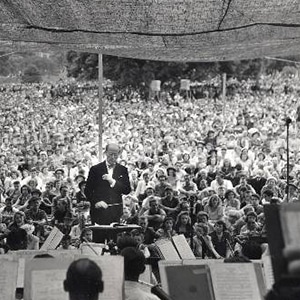

At the helm of this institution is Michael Tilson Thomas whose continual desire to explore, and experiment with, concert formats, makes the New World Symphony a model for modern orchestras. While I was there he spent two days filming a project exploring Beethoven’s 7th Symphony. The project is at an early stage and the final result is not known, other than the fact that Tilson Thomas has a very clear idea of the function of the final result. He wants to create an online educational insight into the interpretational and structural aspects of the symphony. This platform would allow the symphony to be taken apart and put back together in order to investigate the questions which are in the score.

By the very nature of the establishment, Tilson Thomas’ rehearsals with the New World Symphony demanded a different approach from Welser-Möst and the Cleveland Orchestra. In repertoire from Beethoven and Schumann, through Tchaikovsky all the way to Berio, and Duke Ellington, Tilson Thomas trained the Fellows not to play simply reproducing by rote what they have been told to do, but in an active, thinking and understanding way.

Tilson Thomas, with the help of the highest level of coaches, showed the subtle, complex relationships, and the flexible hierarchies that govern an orchestra. In the role of an orchestral trainer Tilson Thomas built up orchestral technique and understanding in the Fellows. For instance the necessity of constant individual subdivision, and the knowledge of the function of the note you are playing, and the careful balancing of the chord helps intonation, and sound. He demanded from the Fellows a very high level of preparation, discipline, but most importantly, individual thought and active playing. He never dictated a result, but respectfully and never patronisingly, built the pathways to open and flexible music making.

In both Cleveland and Miami, the management was friendly, welcoming and gave me time to talk and ask about their respective business structures. Cleveland is very much a model US orchestra. The management is separate from the players, they negotiate contracts every three years, and the union has a powerful presence. During my time with the orchestra it appeared to be a healthy organisation with good audiences and especially in Cleveland following a student ticket initiative, a very diverse audience.

The New World Symphony, in its special place as an educational establishment, offers accommodation and stipends to the Fellows, and manages to combine different organisational models with a very high degree of flexibility, with Tilson Thomas at its epicentre.

The opportunity afforded to me by the Kempinski Arts Programme has given me the chance to study not just the physicality, musicality, rehearsals and leadership of two top conductors, but also two organisations in very different locations and positions in the orchestral market place. I experienced and had the time to reflect upon everything from the flexible and expressive placing of the 2nd beat in a Strauss Waltz to the differing problems facing orchestras and how communication and care by everyone involved can allow an orchestra to evolve without loss of integrity.

“He sees the craft of conducting as having a direct relationship with the operatic repertoire. In particular he spoke of the difficulty of performing Puccini and of how having to deal with the inevitable changes that happen night to night in opera is the best training for the flexibility you need as a conductor.”

I could not agree more.I believe the vast majority of the finest conductors had that direct relationship with opera, especially in their early years.