Lorin Maazel and the American orchestra: a major player

mainLorin Maazel, who died yesterday, started out as a teenaged section player in Pittsburgh and wound up as music director of two of the Big Five – something very few maestros have achieved*. It is still too soon, and we’re still too shocked, to assess Maazel’s impact on the American orchestra. Moreover, almost every conclusion is immediately contradicted by an adversarial perspective. The legacy, however, is large.

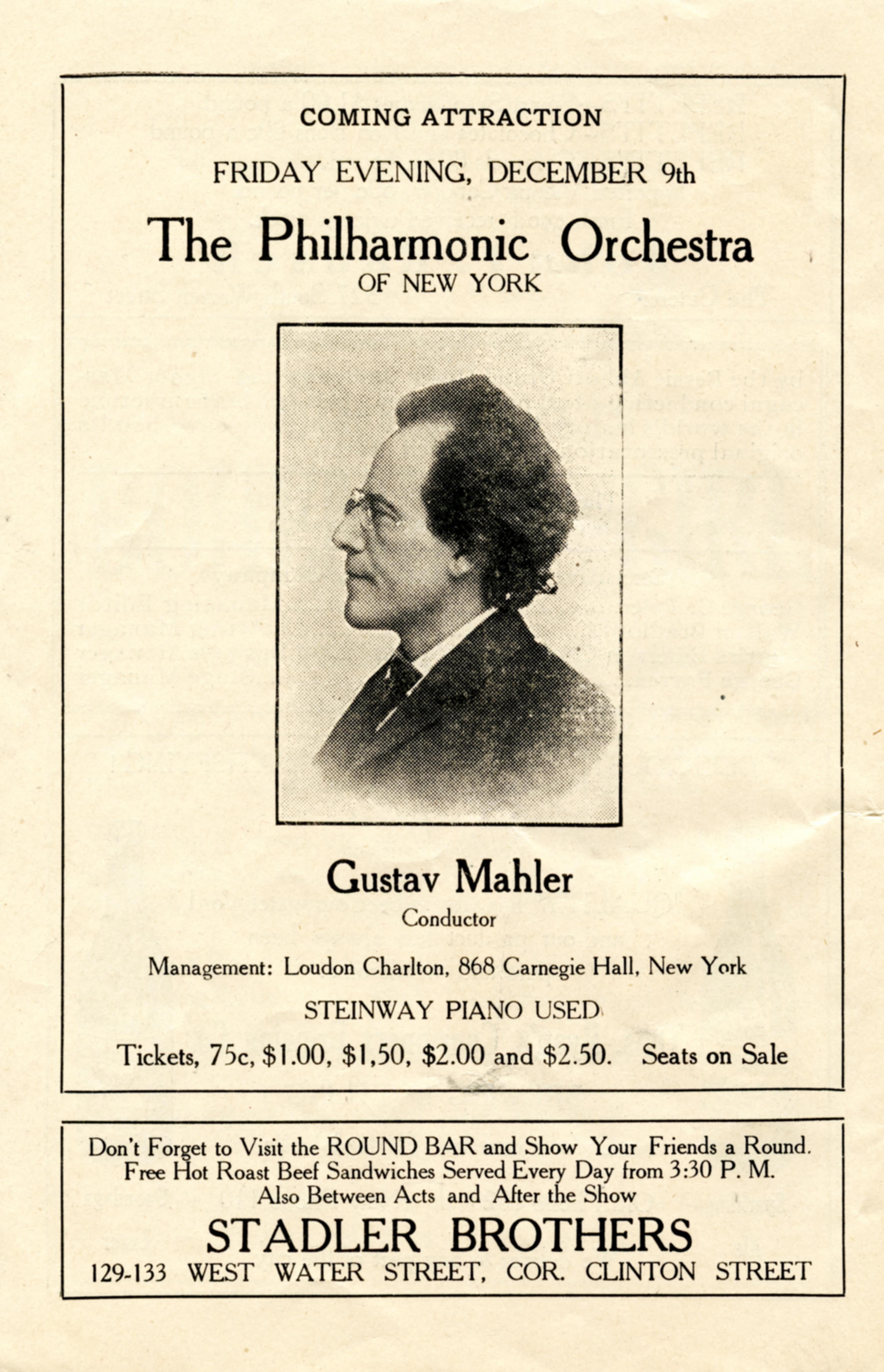

Maazel, having stormed to success in Europe in the 1960s at the Deutsche Opera Berlin and the radio symphony orchestra (then known as RIAS), was named successor to Georg Szell at Cleveland in 1972, a post he held for a decade. Following Szell was an impossible task, though not a thankless one. Musicians heaved a sigh of relief at the removal of Szell’s withering glare and acid tongue.

But the players were not consulted about the succession and most would have preferred the brilliant Hungarian, Istvan Kertesz. Maazel brought vigour, new faces and international swagger. But he made few friends, in the orchestra or the city, and the first local obituary today reflects that he ‘tended to polarise the Cleveland musical community’. He was succeeded by the harmonious figure of Christoph von Dohnanyi.

Maazel returned to Europe in 1982 to head the Vienna State Opera. When the job went sour after three years he returned to the US as music director of his hometown orchestra, in Pittsburgh. The city’s Post-Gazette reports today:

In 1988, the orchestra was old. Many of its members were Mr. Maazel’s former colleagues from his years as a section violinist. After four years without a music director, the PSO had become lethargic.

Mr. Maazel remade the orchestra seat by seat — 37 of them, according to the book “Play On: An Illustrated History of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra” by Hax McCullough and Mary Brignano. The average age of PSO musicians plummeted. Many of those young musicians remain with the orchestra as principals and have come to define the PSO’s sound.

“His job was to attract the quality of players that would make the Pittsburgh Symphony once again a great orchestra,” said Robert Moir, senior vice president of artistic planning and audience engagement.

Maazel stayed eight years in Pittsburgh, before moving to Munich on the highest conductor wage in Europe. He was succeeded in Pittsburgh by Maris Jansons who, musicians hastened to tell me, ‘took the Maazel chill out of our playing’.

In 2002, Maazel succeeded Kurt Masur at the New York Philharmonic. Claudio Abbado and Riccardo Muti had previously turned down the job. In his opening week, he led the first-anniversary 9/11 concert with the premiere of John Adams’s On the Transmigration of Souls. Few regarded that as a cathartic moment. Maazel managed himself and the orchestra well, went on international tours, led an ill-advised mission to North Korea and drew near-relentless hostility throughout from the partisan New York Times. He lasted seven years.

It’s too soon to talk of legacy, but Maazel wrote a chapter in US orchestral history. The bulk of his US recordings belong to the Cleveland era and they give a good impression of how Maazel moved that ensemble from a central-European Szell sound to something more recognisably American.

—–

*The modern exception that springs to mind is Riccardo Muti (Philadelphia, Chicago)

“Big Five” was a term from the 1950s.

It has made no sense since the 1970s.

@SDREADER:You´re so right!!!There are big 12 or 15 American Orchestras!

It was said of Stravinsky, that his music is more admired than loved. The same might be true of Maestro Maazel. I heard him many times in the post-Szell years in Cleveland and in his recent tenure in New York. He could be either staid or electric. I heard him with the NYP do a marvelous Mahler 5th—from memory, of course. He was a huge talent and had an amazing career.

Maazel does occupy rarified air in terms of American directorships. Rodzinski helmed three Big fives (Chicago, Cleveland, and New York) and Leinsdorf had Cleveland and Boston, all amazingly contemporaries of Maazel during his long career.

What Norman says about Maazel’s impact on the Cleveland Orchestra may be right. I have just been listening to Debussy’s Jeux with the Cleveland Orchestra under Maazel. Without wanting to resort to cliches, it certainly embodies some of the characteristics long associated with this conductor – cool, refined, precise; quite different from but as equally compelling as, say, Haitink’s famous recording with the Royal Concertgebouw, which has a more sensuous allure.

To complicate matters, however, what follows is an extract from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in relation to Maazel’s impact on the PSO: “The orchestra returned to earlier sonic roots: Mr. Maazel drew out a warm, Germanic sound more akin to music director William Steinberg’s approach than Andre Previn’s later, more transparent style. Mr. Maazel called it ‘a European sound, dark and broad, beautiful’ according to ‘Play On’.”