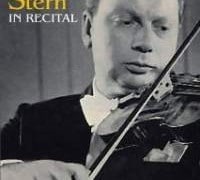

In defence of Isaac Stern

mainIn the interests of balance, and in the belief that we all good made up of good and bad in unequal parts, we are publishing the following response to recent revelations on www.slippedisc.com about the great American violinist.

Dear Norman,

Below is what I said at the June 1987 Conference of the American Symphony Orchestra League (now the League of American Orchestras) when I had the honor of presenting the League’s Gold Baton Award to Isaac Stern. Re-reading it now, after all these years, I think it is still a good summary of who Isaac was, and what he did. In the 40 years or so that I knew him I never heard him speak ill of another musician. He did often suggest artists to me that he thought were talented and deserved a chance to perform – something I rarely experienced other soloists doing.

While I obviously can’t prove that Isaac Stern never spoke against other musicians, or prevented them from appearing at Carnegie Hall or the 92nd Street Y, I agree with you that he could not have destroyed the careers of musicians who would otherwise have made it to the top. There were plenty of other reasons that Aaron Rosand, Ivry Gitlis and Erick Friedman’s careers did not go as well as they would have liked, and it is utter nonsense to say that Szeryng’s and Heifetz’s careers were in any way damaged by him.

All the best,

Peter Pastreich (former Executive Director of the Nashville Symphony, the Kansas City Philharmonic, the St. Louis Symphony, the San Francisco Symphony, and the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra)

PRESENTATION OF GOLD BATON AWARD

TO ISAAC STERN

June 12, 1987

My first encounter with Isaac Stern was in March, 1960. I was Manager of a community orchestra in New York City called the Greenwich Village Symphony, and we were going to perform the Mozart Sinfonia Concertante with our Concertmaster and principal violist as soloists, in the auditorium of PS 41 on West 11th Street. The violist knew Isaac Stern, the famous violinist, and thought he might get him to agree to be photographed with our conductor and soloists, and that one of the Greenwich Village weekly newspapers might print the photograph. They were invited to Mr. Stern’s apartment, with me going along to take the picture, and as long as we were there, Mr. Stern listened to them play the entire piece, then spent over an hour coaching them in it, and finally offered our Concertmaster, whom he’d never met before, the use of a better violin for the performance. In the 27 years since then, I, and all of you, have had many more opportunities to witness Isaac Stern’s generosity, his caring his knowledge, and his passion for music.

Isaac Stern was born in the Ukraine and was brought by his parents to San Francisco when he was 10 months old. He began to study the violin at 8 and made his debut in the Saint Saens b minor with the San Francisco Symphony at 15, a year later playing the Brahms Concerto with Pierre Monteux and the San Francisco Symphony. In the 51 years since, he became a major cultural force and the greatest violinist America had produced.

Isaac Stern has honorary degrees from a dozen universities including Yale, Columbia, Johns Hopkins and the University of Tel Aviv. He is a Commander of the French Legion of Honor, has the Danish Commander’s Cross and is a Kentucky Colonel. He has received the Wolf Prize, Israel’s most important prize, for service to humanity; the Kennedy Center Award, presented by the President of the United States, for lifetime achievement in the Arts; and the first Albert Schweitzer Music Award for “a life dedicated to music and devoted to humanity.” Today the American Symphony Orchestra League has the privilege of presenting Isaac Stern with its Gold Baton Award, the highest honor this nation’s symphony orchestras can bestow.

What is it that makes Isaac Stern so unique as a man and as an artist? First, his incredible energy, which permits him to play concerts and recitals, record and play chamber music, plan and supervise projects in New York, Paris and Tel Aviv, stay in touch by phone with musicians, managers, composers, instrument dealers, politicians and heads of state, all simultaneously, and still to be a loving and devoted husband to Vera and father to his children, Shira, Michael and David.

Then, his extraordinary loyalty. In 1940, Sol Hurok became Isaac’s manager, and he remained his manager until Mr. Hurok died in 1974; ICM has been his American manager since then. Michael Rainer, and Rainer’s father before him, managed Isaac in France since 1949, and in that same year, Harold Holt became his English manager. Both relationships continue strong after 38 years. He has recorded for one company — CBS Records — for 41 years. For 33 years, from 1940 to 1973, Isaac Stern’s accompanist was Alexander Zakin, the longest such musical relationship in history. No artist has appeared as often with the New York Philharmonic, or the San Francisco Symphony, as Isaac Stern. Married, so far, for 36 years, Isaac’s many friendships are close and unwavering. It is inspiring to me to see, when Isaac returns to San Francisco to play with our orchestra, as he has 94 times in the last 52 years, how he always spends time with the friends of his childhood; how he never forgets those who helped him as a young man. At every one of his San Francisco concerts, Mrs. Blinder, the 91-year-old widow of Naoum Blinder, Isaac’s teacher and the San Francisco Symphony’s Concertmaster 40 years ago, sits in the auditorium, proudly beaming at Isaac.

Third, there is the breadth and depth of Isaac Stern’s interests and accomplishments. Fluent in five languages, an expert on international relations, politics, education, a connoisseur of string instruments and bows, of food, wine and cigars, Isaac’s musical interests and knowledge are comprehensive and far ranging. He has recorded over 200 works by 63 composers and has played virtually every important work written for the violin. He gave the first American performance of the Bartok First Violin Concerto and the first performance of the Leonard Bernstein Serenade. He made the first recording of those two works, of the Samuel Barber and the Hindemith violin concertos. Penderecki, Rochberg, Dutilleux and Peter Maxwell Davies all wrote major works for him and he not only performed but recorded all of them. His influence has been felt in the world of television and film, including his appearance, as Eugene Ysaye, in the film “Tonight We Sing,” his “ghosting” for John Garfield in “Humoresque,” his performance on the sound track of “Fiddler on the Roof,” and the documentary films “A Journey to Jerusalem” and “Mao to Mozart: Isaac Stern in China,” which won an Academy Award.

Fourth, there is Isaac Stern’s social conscience. In 1963, when I was General Manager of the Nashville Symphony, there was only one great and famous guest artist we could get to appear with our orchestra — Isaac Stern. There were other great and famous artists around, but their fees were too high; only Isaac kept his fee low enough so he could be heard in cities like Nashville, Tennessee. Some other aspects of Isaac’s social conscience are obvious: He saved Carnegie Hall from destruction and preserved it as a great cultural resource for New York and this country, and he still serves as President of the Carnegie Hall Corporation. He was the founder of the Jerusalem Music Center in 1973 and is Board Chairman of the America-Israel Cultural Foundation. These things we all know, and they represent the public side of Isaac’s social conscience. But what many of us don’t know is the private side. Possibly we know how he helped Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zukerman and Shlomo Mintz, bringing Pinky and Shlomo to the United States, arranging for scholarships for them to study with Dorothy Delay, finding them management and helping their careers. But when I called Dorothy, she told me about the many other young music students she’s taught, who arrive in New York without friends or money, and about Isaac finding them friends of his to live with, sending them to his dentist, at his expense, getting them instruments and bows, and most important, listening to them play. Dorothy said to me, “People know that when there’s any really talented kid, Isaac will want to know. He’ll always find time to listen.” Dorothy said, “I love Isaac — and I’m so happy he’s there.”

But the most important source of Isaac Stern’s uniqueness is Isaac Stern, the musician. In his playing we hear the spirit of his musical heroes: Kreisler, Heifetz, Hubermann, Ysaye, Oistrakh . . . and Casals, who, like Isaac, could leave no note uncaressed. His playing is characterized by a depth of understanding of the composer and by a unique ability to communicate the composer’s innermost meaning to his audience. When he plays, Isaac talks to us, he sings to us, he makes love to us.

When someone recently asked another long-time friend of Isaac’s, Alexander Schneider, the question, “Who is the best of the young violinists?” Sasha replied, “Isaac Stern.”

We’ve all heard the joke about two old people walking on 57th Street. One says to the other, “I heard Isaac Stern last night,” and the other replies, “Yeah? What’d he say?” We’re here to honor Isaac for what he said, for what he played and for the way he played it, for what he did, and for what he has done for music and for the people who make and love music.

What’d he say? What’d he do? Very likely more than any other musician of our time.

Isaac, it is a great honor for me to present you with the American Symphony Orchestra League’s 1987 Gold Baton Award.

– Peter Pastreich, 12 June 1987

Comments