Whatever happened to Gavin Bryars?

mainDown in the publishing vaults of Schotts, beside the River Main, they have been rummaging through Beethoven’s nail clippings and sundry other relics to see if anything got left out of their most performed works of the 21st century.

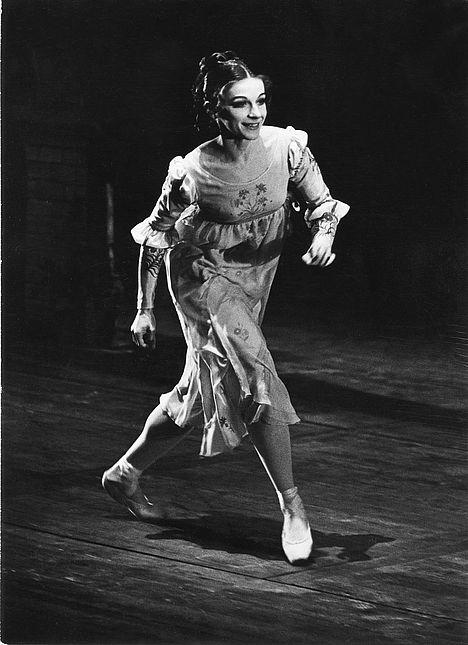

Sure enough – why didn’t anyone spot the omission? – top of the pops for Schotts is the compelling British composer Gavin Bryars, whose Tchaikovsky-based Amjad for string quartet has had its socks danced off by sundry companies in Edouard Locke’s exciting choreography. Amjad scored 115 performances since its Ottawa premiere in April 2007.

Three works by Penderecki have also done pretty well, as has one by Steve Martland.

Computing them into the rankings, here is the updated Top Twenty:

20 John Adams: The Dharma at Big Sur (2003) for electric violin and orchestra, 72.

19 Steve Martland, Tiger Dancing (2005), 73

18 Jörg Widmann, Hunt Quartet (2003), 74

17 Kryzstof Penderecki, Ciaccona (2005), 76

15= Penderecki sextet (2001), 79

15 Oliver Knussen violin concerto (2002) 79.

14 Detlev Glanert’s opera, The Three Riddles (2003) 80

13 George Benjamin Dance Figures for Orchestra (2004), 82

12 Detlev Glanert opera Jest, Satire, Irony and Deeper Meaning (2000) 83

11 Philip Glass, Concerto Fantasy, 87

Top Ten

10 Colin Matthews Pluto (2000), 87

9 Krzystof Penderecki Concerto Grosso (2001) 89

8 Christopher Rouse Rapture (2000) 97

7 Howard Goodall’s Requiem (2008) 102.

6 Nathaniel Stookey, The Composer is Dead (2006), 104

5 Joby Talbot Entity (2008), 110

4 Gavin Bryars, Amjad (2007)

3 Tan Dun, Crouching Tiger concerto (2000) 139

2 Joan Tower, Made in America (2008), 145

1 Karl Jenkins Requiem (2004) 311

These new entries do not materially change the conclusions of the previous chart and report. Dance remains the most vigorous driver of contemporary music performance – considerably more so, to general astonishment, than movie scores.

“Dance remains the most vigorous driver of contemporary music performance – considerably more so, to general astonishment, than movie scores.”

Which does rather beg the question…have you talked to John Williams’ publisher? The UK symphony orchestra for which I work hasn’t played just one of the top twenty works (though a Goodall Requiem is scheduled) – but it’s played extracts from “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” about twice a season since the piece was written, in 2001.

Howard Shore’s dire “Lord of the Rings” has had quite a few outings too. Are we counting live performances of film scores? I see we are in Tan Dun’s case.

NL replies: Williams has several publishers, including Boosey and Alfred (Ca.). None has put in big numbers for him – perpahs because the recent work is less popular, much less, than Star Wars and Schindlers List.

The way to find the living composers who will continue to be performed in, what is your time frame again?, fifty years?, is NOT to determine which individual works are played most often.

There was a time when a work like, say, Ferde Grofe’s Grand Canyon Suite was performed a lot in the United States, perhaps more than any single work by a composer like Aaron Copland or Charles Ives. And the Grand Canyon Suite is still programmed some, but no one thinks about Grofe much at all.

What I think you should be considering is which composers have the most different works performed each year.

The composers who are currently living and working in the early 21st century who will still be best known fifty, or a hundred years from now are those composers who have created a body of works that orchestras will continue to draw from when programming multiple concerts in multiple seasons.

One of the reasons that some of the composers you’ve called “superstars” don’t show up on a list like yours is that they don’t have ONE piece that gets programmed all the time, they have several or many pieces that each get programmed often.

You’ve also wondered about several composers who have strong reputations but haven’t shown up among their publishers best sellers. Artists such as Meredith Monk, Michael Nyman, & Steve Reich have written comparatively few works for standard ensembles and/or soloists. Most of their works have been created for ensembles, often with quirky instrumentation or, at least in the case of Monk, for performers trained in unusual techniques, that will take longer to become part of anything like a standard repertoire (if that’s possible in these cases).

“Williams has several publishers, including Boosey and Alfred (Ca.). None has put in big numbers for him – perpahs because the recent work is less popular, much less, than Star Wars and Schindlers List.”

Indeed – but the “Harry Potter” score is, I suspect an exception. This is just a gut feeling, but I can’t think of a season since 2003 when our orchestra hasn’t played it at least twice; usually in schools/family concerts. For the under-18 audience, it seems far more resonant than earlier, arguably better scores like “Close Encounters” and “Star Wars”.

Of course, Williams has put some of his most recent scores (including Harry Potter, Munich, and Catch Me if You Can) for sale in commercially-available concert suites. Orchestras don’t need to hire them from publishers. So once more, it’s possible that – as with Rutter carols – many more performances are taking place than publishers are recording. Possibly few other contemporary composers could afford (financially) to do this, though I’d argue that many more can’t afford (artistically) not to do so!

NL replies: Richard, you may well be right. But it’s unlikely that successful composers would keep such triumphs quiet for very long. If Williams, Rutter or anyone else wishes to submit audited performance stats, I’d be happy to include them in the LCS charts.