6 finalists face unseen piece of music

mainThe finalists at the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels are:

Jonathan Fournel, 27, France,

Keigo Mukawa, 28, Japan,

Sergei Redkin, 29, Russia,

Tomoki Sakata, 27, Japan,

Dmitry Sin, 26, Russia,

Vitaly Starikov, 26, Russia.

Each will perform a concerto, plus an unseen piece by Bruno Mantovani.

It kicks off Monday.

Performing an unseen work is a really interesting element. Is it completely unseen, or do they have a fixed time in which to prepare it or even just have sight of it ?

Each day only one finalist will enter concert hall and be given the unknown score. So I suppose each has the hole day to practice it + orchestea rehearsal + final competition performance on same evening.

Finalists of the Queen Elisabeth stay one week in isolation (no outside contact with the world) at the Chapelle Musicale Reine Elisabeth in order to adequately get acquainted with the new work and practice their other concerto ahead of the rehearsals and concert with the Belgian National Orchestra.

As has been the custom, the commissioned is completely unheard of (and to my knowledge, no “demo” recording is provided), meaning that the finalists rely entirely on their own musical capacities in order to prepare. Some even memorise the work in that short span of time (I remember seeing the italian Alberto Ferro playing by heart the wonderful commissioned piece “A Butterfly’s Dream” by Claude Ledoux in 2016).

I think they are given one week to prepare it.

It is a tradition for this competition. Seems to work for them. There may be other ways as well to venture into new music. In the concert world, rarely is a musician called upon to learn something new so quickly. If you have a composition in your repertoire list for short notice, you may be in the running to assume an emergency replacement engagement. Most new pieces are delivered in a timely arrangement, per the commissioning agreement. Speed learning does not make an artist. Perhaps a chamber music round would be more of an indication to attest to their abilities to perform chamber music with others. I would opt to send the commissioned work to the contestants as soon as they are admitted to the competition. Give them a reasonable time to digest the new piece and bring something significant to it. That would provide more of an indication if they could prepare and premiere new works.

3 Russian in finals. Sergei Redkin’s special. Wish him to win. Superb pianist.

I highly recommend comparing Mr. Redkin’s and Mr. Mikdad’s Mozart concerto rendition (the same piece, No. 17 in G Major, KV 453), especially with only audio and no video.

At first, I didn’t like Mikdad’s Mozart very much because he seemed very nervous and tense in the very opening movement — he didn’t move much at all, although there were absolutely no faults to his playing. But then I listened (with video) to Mr. Redkin’s Mozart and was disturbed by his extraneous motions. Mr. Mikdad seems to hum along a little when he plays, which is also a bit distracting, but is a common “bad habit” of otherwise gifted players which can be easily overcome if one really wants to.

So I opened a PDF file with the score and watched that while playing the audio in the background. Very illuminating, indeed!

As to the other preliminary rounds, I found that Aidan Mikdad’s playing was on a completely different level than Mr. Redkin’s playing. But everyone will have there own opinions.

I totally agree with Mr. Hairgrove. But that was not the worst of it. If you watch Mr. Starikov perform the Mozart K488 concerto in the semifinals, you will notice him bopping his head to the rhythm, especially in the third movement. This is very poor performance practice. I used to engage in extraneous movements when playing Mozart until I visited the ballroom of the Schloss Schoenbrunn in Vienna. Then I realised that performing in such a grand space and in front of the emperor would necessitate keeping all extraneous movements to a minimum. Mr. Starikov’s performance stylistics of Mozart would not get him a pass in most conservatory exams, let alone into a final of a prestigious international competition. As for Mr. Redkin, his advancement into the final is totally puzzling to me. His fingers got jammed in the first section of Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasie making him miss numerous notes. Also, he kept on having to push his glasses up his nose throughout his whole semifinal performance. This is patently poor preparation. Before one shows up to compete at any level, one should make sure that one’s glasses fit well enough that they do not become a distraction throughout the performance.

At any rate, it is certainly an opportunity to give some Belgian composers a little exposure. 🙂

It would be interesting to do a survey of how many “oeuvres imposées” continued to enjoy performances outside of the competitions where they were premiered?

I enjoyed listening to the required “Nocturne” by Pierre Jodlowski in the semifinals very much … although parts of it seem more of a nightmare to me than some pleasant dream, I think it is a very effective piece (especially in the rendition by Aidan Mikdad, one of my favorites so far — alas, he did not make it into the finals).

What is interesting is that this challenge – of being given next to no time to bring a brand new piece to performance level under nerve racking conditions — pretty much describes the day to day life of a musician, including soloists, in the time of Mozart, Beethoven and such. Franz Clement premiered the Beethoven Violin Concerto with about that much familiarity, and was likely playing off a scribbled nightmare of a score to boot.

To a certain extent a busy violinist in a symphony orchestra might find unfamiliar repertoire being thrown at them at short notice, particularly for recording sessions which are not the consequence of a concert performance, but there MIGHT be at least a listening familiarity with the piece and at any rate this or that tiny blunder won’t likely be heard except by your stand partner.

But I’d have to think the recording session /advertisement jingle/film soundtrack players face this challenge more regularly, every day perhaps. But I grant that the QE Competition does not exist so that its winners can be session players, although those players can be marvelous artists. I don’t think it is so much a matter of trying to replicate a situation that they are going to have to face in their careers so much as testing how they fare in a difficult circumstance.

There HAVE been after all concert artists, the much-sneered-at Willi Burmester comes to mind, who largely created a reputation based on endless repetition in practice of a select virtuoso repertoire, rather than really being masters of the underlying technique(s) — unlike genuine technicians who can play anything put in front of them. Burmester was said to be able to impress, by dint of pure drudgery, in pieces by Paganini in his famous recital that could be said to be otherwise beyond his abilities.

You are correct – speed learning has nothing to do with art. It is, however, interesting to hear everyone (or at least the finalists) play the same piece, so for once it is an ‘apples to apples’ comparison. One of the aspects of music competitions that I have a hard time with (and there are many more…) is that everyone can play pretty much whatever they want, so now subjectivity is turned to 11. Comparing one’s Appassionata interpretation to another’s Goldberg interpretation never made any sort of sense to me.

Note: these are pianist finalists

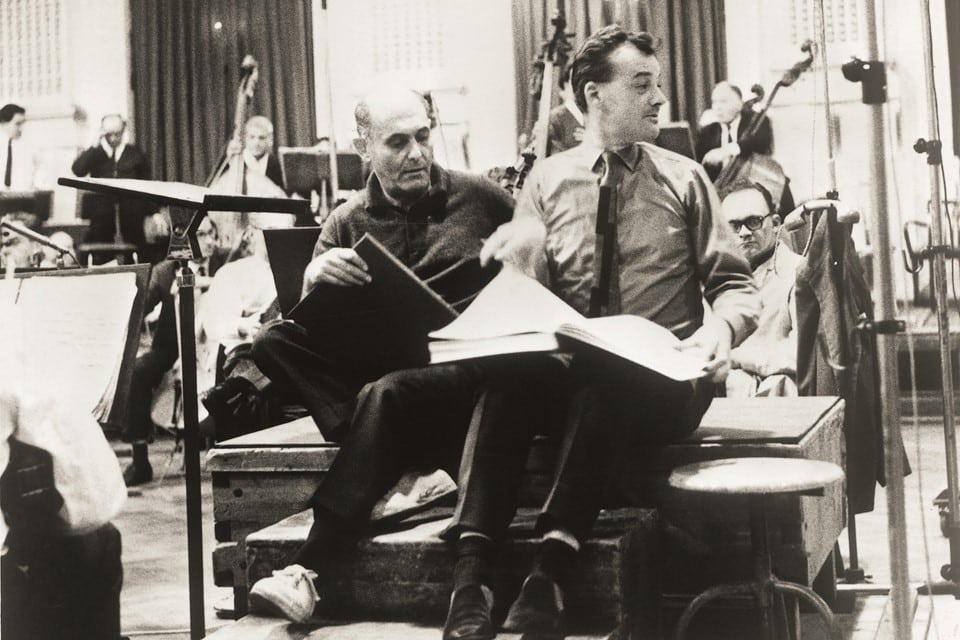

You do know it is piano this year.? And a violonist is on the picture…..

Very Nice article and good work. Congratulations.

We are also in the field of music but it is Indian classical Music. My father is a disciple of Pt. Bhimsen Joshi Ji and eminent Indian classical singer with International fame. I am also trained in the field of Indian classical singing by my father and now a have been performing in the field for over a decade. If you wish to collaborate, we would be obliged. Many people love Indian classical music for it’s meditative, immersive and uplifting nature. It provides a sense of peace and elation. Although it is difficult to master, it provides immense fulfilment.

http://www.bhimsenjoshisangeet.com

So many Russian pianists in the finals… This is not an accurate representation of young piano talent in the world today.

Not just the number of Russian pianists but also where the finalists are studying.

2 of the 6 finalists are Artist Diploma students at the Queen Elisabeth Music Chapel itself. And one of them, Mr. Redkin did not make this known until after his advancement to the final.

Mr. Starikov was a student of jury member Eliso Virsaladze until just 2 years ago.

Mr. Sin is a student of the Russian teacher Rena Shereshevskaya in Paris.

Another finalist is a student of the conductor of the Chamber Orchestra of Wallonia that played the Mozart concertos with the semifinalists.

Also very interesting in this context is the jury member A. Volodin who is a former student of E. Virsaladze — not the first time they have been together on juries at the same competition, and it is not the first time that students of E.V. advance to the finals and win prizes when she is in the jury (e.g. Aleksandr Shaikin in 2015 at the Geza Anda competition, who won 2nd prize).

So Virsaladze cannot vote for her students, but Volodin can.

The Paris Conservatoire used to (may be still does?) annually commission new solo works to test their students on. A large portion of the trombone solo repertoire that is commonly played today originated as Conservatoire “concours” pieces.

Will this Mantovani piece have as much success?

[Anyone still reading this thread??]

I just wanted to comment that in light of the numerous speculations about having one’s own students in the running for a competition, I was hunting around on the internet for information about previous issues of the Tchaikovsky competition.

There are some interesting clips (newsreels in Russian, but with English subtitles) about the very first two or three competitions. In 1966, the third Tchaikovsky competition, the winner in violin was Viktor Tretyakov. The announcer in the clip mentions that he had “serious competition” from two other contestants, both students of David Oistrakh (who was in the jury): Oleg Krysa and Oleg Kagan. The clip I am referring to can be found here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XQxAw5NOpFc

My point is, that as long as everyone is honest and the perceived level of playing justifies winning the accorded prize, nobody really cares about the fact that someone on the jury is teaching one or more competitors. It is only when the level is noticeably different, and unfair eliminations are done, that the specter of “backroom politics” suddenly becomes an issue.

The problem here is that in the Soviet Union in the 1950’s-60’s with their centralized educational hierarchies, the only capable jurors (much less the best qualified jurors) were teachers of the very best Russian talents, and practically all of these were students of the same institution.

Today, the rationale for choosing a jury must be so much more complicated. And certain Mafia-type networks amongst the professors who tour from one competition jury to another are bound to pop up.