A studio legend calls ‘cut!’ at 95

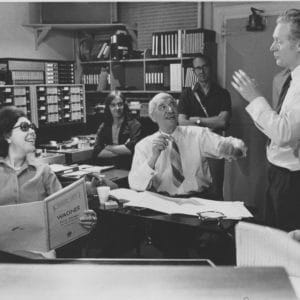

mainAnthony Faulkner remembers Abbey Road balance engineer Chris Parker, who died on April 15:

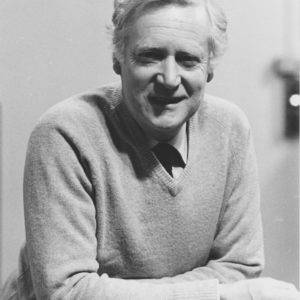

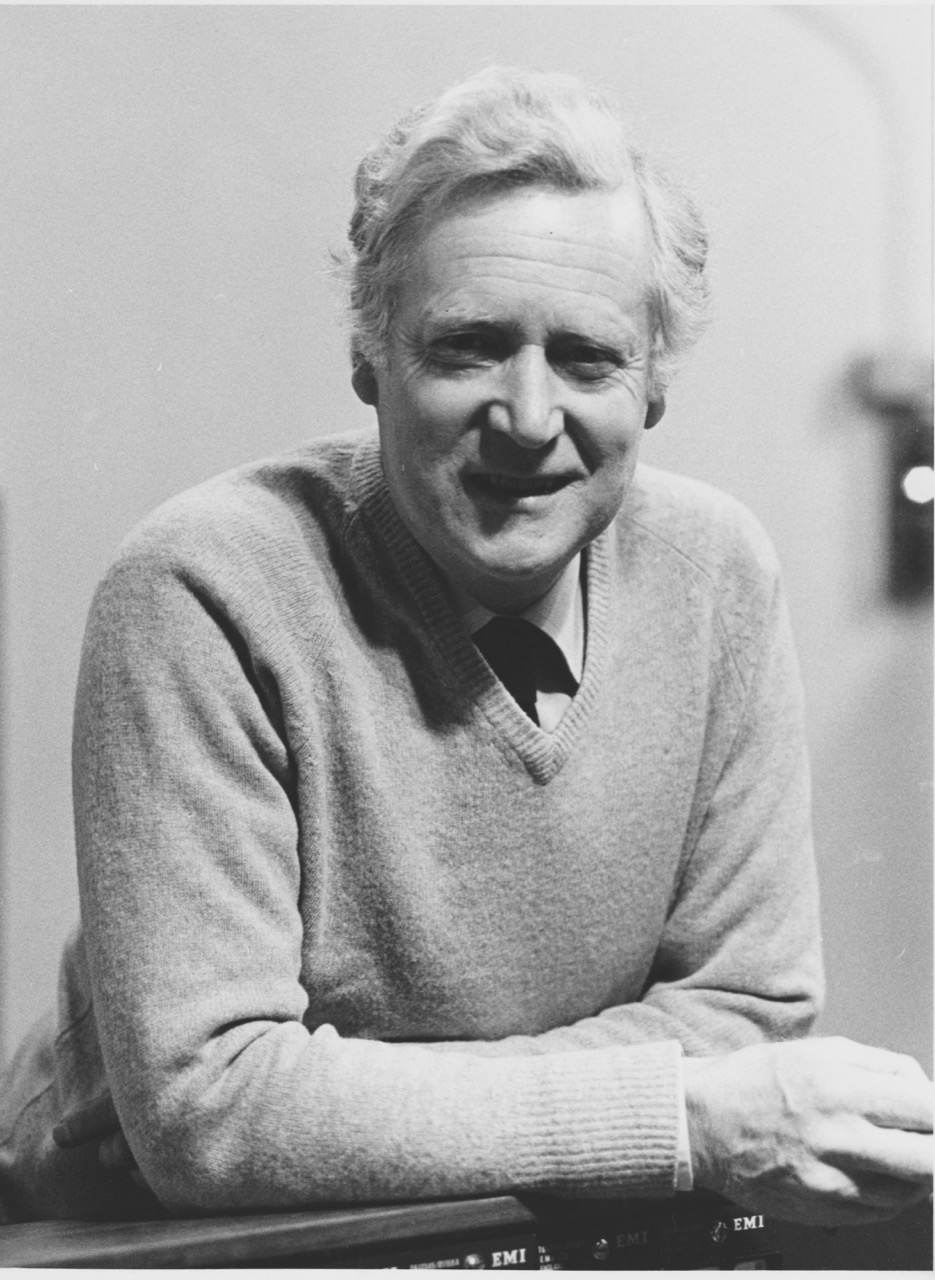

Christopher Parker R.I.P. (1925 – 2021)

Anyone who has collected classical recordings will find Chris’s name on countless fine recordings, made during his extended career at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios. For me, Chris was an inspirational character and hugely encouraging and supportive during my earliest years. His recordings are hallmarked for honesty and integrity, eschewing reliance upon dirty tricks in the studio which undermine credibility.

Born in Lewisham in July 1925, Chris was the third of four children born to Harry Stanley Parker, a civil servant and Gladys (née Whalley). When he was 14, to avoid the bombing in London Gladys took Chris to stay with her sister in Penarth, where he met the 11 year-old Eva Gruenbaum who had recently arrived as a Jewish refugee from Würzburg. They married in 1951 and were partners for 71 years until her death in 2010.

Before his call-up to the Navy in 1942 Chris worked as a mechanical engineering apprentice at Kodak and after service in signals at the end of the war in Sri Lanka and Singapore he returned to London to study piano at the RCM.

Chris joined EMI in 1951 on a wage of eight pounds and five shillings a week. His first job was to operate experimental “tape-machines” which were at that stage used as a back-up to the standard recording medium of wax-cutting lathes. He was soon instrumental in engineering some of the very earliest stereo recordings. As an example, Walter Legge’s 1956 Kingsway Hall production of Rosenkavalier conducted by Karajan with Elizabeth Schwarzkopf, Christa Ludwig and Teresa Stich-Randall was originally released in mono, but the version we enjoy today was recorded by Chris working alone in a side-room at Kingsway Hall, using his own rig of experimental microphones to capture this iconic performance in the gradually-emerging new stereo format. The microphone techniques which formed the starting point and backbone of Chris’s approach were based in credible physics with the objective of capturing a performance event faithfully, – not arbitrary nor interventional to draw attention to the engineer. Chris had been one of few engineers of his generation to read music.

During the following years until his retirement in 1987 he collaborated with a veritable ‘A to Z’ of international artistes, a list of whom would fill this obituary; Ashkenazy, de los Angeles, Ameling, Bliss, Beecham, Boult, Boulez, Barenboim, Callas, Chekovsky, Cortot, Caballé, etc, etc. He recorded most of the greatest orchestras in the world, working frequently in Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, Vienna, Berlin, Paris and Prague and engineered discs with countless chamber and choral ensembles such as the Amadeus Quartet and the choir of King’s College, Cambridge. He worked on several enduringly iconic discs which are still clearly dominant in the catalogue. A prime example is the1988 recording of the Elgar Cello concerto with Jacqueline Du Pré and the Sea Pictures with Janet Baker conducted by Sir John Barbirolli. His writings contain dozens of enduringly amusing stories about performers and recording sessions, (many of which would sadly be unrepeatable in print) but perhaps just one of which I can share here. These are Chris’s own words.:

“While I was setting up the mixing desk in Studio One for Jaqueline du Pré’s recording of the Elgar Cello concerto, Sir John Barbirolli and the producer Ronald Kinloch Anderson were chatting together in the control room behind me. “Hey John-” said Ronald, “you were a cellist- YOU should really be recording the Elgar!” “Ah yes,” grinned Barbirolli – “but who would conduct?”

Passionately creative until the very end – Chris would often spend hours sitting at the piano improvising and composing. Until the recent lockdown, despite being well into his nineties, he would think nothing of driving solo for several hours after dark to hear a favourite ensemble giving a concert. The walls of every room in his Sherborne cottage were covered with his own paintings and portraits, he was a very active and keen gardener and completely transformed the simple garden where he lived into a veritable panoply of fabulous colours and shapes.

Chris is survived by his three children, Ruth, Nicholas and Deborah, his partner of the last eight years Janet Matthews, nine grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren, the youngest of whom, Michele, was born at five minutes to midnight on April 15th, the very day of Chris’s own death.

A great man, whose legacy has enriched, enriches and will continue to enrich so many lives.

A true legend, his is a name I have long looked for associated with recordings.

I first met Chris Parker in April 1961 when visiting Abbey Road Studios for the first time. In those days he was just one of the younger engineers who worked on stereo balancing. His first stereo recording were in December 1954 and in the following year made EMI’s first stereo recordings in Kingsway Hall in February. He balanced the stereo versions of the last recordings of tenor Beniamino Gigli and the Australian bass-baritone Peter Dawson in March and May, followed by the first opera that EMI made in stereo: “The Beggar’s Opera” with Sargent, later by “Le nozze di Figaro” with Gui (using a set-up comprising a crossed pair of stereo microphones plus two ‘outrider’ ones). Even today it still sounds remarkable lifelike. Another classical Parker recording was Karajan’s “Falstaff” dating from 1956. Chris became EMI’s senior balance engineer in 1964 and remained so until his retirement in 1987. His last visit to Abbey Road Studios was in September 2016 when he and his fellow contemporary Robert Gooch were interviewed. One of the giants of the classical recording industry

Gui’s Figaro remains my favourite version, always the one I turn to for the superb conducting, marvellous cast and superb engineering.

A legend. There are still unreleased early stereo recordings made by Chris, which are being issued by FHR for the first time. We spoke with him on a few occasions – it was interesting to be in touch with Chris including him showing us his original microphone setups at Abbey Road for the early stereo recordings. RIP Chris

Many of his recordings still sound superb, sixty years on.

P.S. The Elgar cello concerto was recorded in 1965, not 1988. This is a link to the original tape: https://pbs.twimg.com/media/D3EJE6GX0AA89UP?format=jpg&name=4096×4096

A wonderful obituary of a superb recording engineer. His anecdotes really ought to be published — at least, the ones about people no longer living. Let a publisher decide what would or would not be “repeatable in print”! And let someone look over his compositions: would any of them be worthy of performance?

It goes without saying that his lasting legacy will be his catalogue of wonderful recordings.

EMI LPs with the credits Christopher Bishop & Christopher Parker were a guarantee of quality recognised by collectors. Nicholas Parker became a record producer.

There is no disputing the breadth and quality of Christopher Parker’s work for EMI. His early and later stereo recordings for that label still sound astonishingly great after all these years, and he was certainly one of the most renowned of classical engineers.

However, the claim in the posting that they are “some of the very earliest stereo recordings” is nonsense. Those occurred due to the work of the engineers at Bell Laboratories in the US as early as 1934, and some of those recordings (performed by Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orch.) have been issued on LP and reissued on CD.

Parker’s may very well have been the earliest stereo recordings of EMI, which was notoriously last among the major classical labels to embrace stereo, due to the intransigence of Walter Legge, who thought stereo sounded unnatural compared to mono.

But surely Parker’s death deserves a more sensitive headline than “A STUDIO LEGEND CALLS ‘CUT!’ AT 95”. I consider that to be in very bad taste.

Also it’s plain stupid. The engineer plays a more passive role at sessions and even the producer is likely only to interrupt the performers if something has really gone awry – and then in a tactful manner.

Did you ever witness Christopher Parker at work? Did you ever meet him? If not, how can you possibly comment on his working practices. I attend over 50 sessions at which he was balance engineer. A superb professional in every way.

The producer, and the engineers under his control, can have a tremendous impact on the musical results. The alleged clarity of most Boulez recordings stems from interventionist producers, such as Andrew Kazdin at CBS who oversaw much of the Boulez repertory until he moved to DG. And even there Boulez received the full-bore “Tonmeister” engineering treatment, heavily influenced American production techniques. While not so multiple-mono sounding as the Kazdin recordings they are interventionist mixdowns nonetheless and, as a result, not nearly as longlastingly beautiful as the more gentlemanly recordings regularly obtained from EMI’s Parker/Bishop pairing.

1988? I’m afraid Norman, that Jir John was already very dead by then, and so was Jacquie, after half a life severely punished by MS…

Has anyone ever called “Cut!” in a recording studio? They do on film sets.