Steven has allowed us to share these memories of the extraordinary Ivry Gitlis, who died today at the age of 98.

Goodbye to Ivry.

So Ivry Gitlis is gone, at the age of 98. To say that he was a ‘character’, who will be greatly missed, would be a ridiculous under-statement…

Born in Haifa – originally named Itzaak – to Russian-Jewish parents in 1922, he must have been an amazing child prodigy. At the age of eight, he was taken to see the great Bronislaw Hubermann; Ivry always remembered that Hubermann was sitting by a lake, dangling his feet in the water. This meeting, wet feet notwithstanding, led to Ivry making his way to Paris, accompanied by his (I’m sure – one could always feel it in Ivry’s personality) adoring mother, where he met and played for Thibaud and Enesco, and was accepted into the class of Jules Boucherit at the Paris Conservatoire at age 11. It feels strange, though, to use the words ‘Ivry’ and ‘Conservatoire’ in the same sentence. There was no way that Ivry would ever have fitted into any institution. His talent, his character, his charm, even his career – they were all wildly unique, impossible to tame, to pigeonhole….

His studies over, he embarked upon his career, playing with major orchestras all over the world, and making some jaw-droppingly brilliant and vivid recordings. But a conventional career was never going to be for him – no more than a conventional approach to music. He wanted to play concerts whenever and wherever he could, true, and enjoyed enormous success, particularly in France and Japan, and to a certain extent in the US, where he formed friendships with Heifetz and Stern; but he also wanted to branch out with or even without his violin away from the concert platform. He acted (as a magician!) in a film by his friend Francois Truffaut; toured though many parts of Africa; worked with Marcel Marceau and Stephane Grappelli; took part with John Lennon and Yoko Ono in the Rolling Stones’ Rock’n’Roll Circus; and so on. His playing and his personality were on the controversial side of non-controversial, I have to say; either you loved him and his playing – or not. He aroused extreme reactions in people; they either got it, or they didn’t. He wasn’t particularly happy about that – he wanted to be universally loved; but he had to accept it. He would never have dreamed of compromising for anyone.

Although I of course knew the name, I really had very little idea about him before we met in Tel Aviv in, I believe, 1996. I was playing a concert there with the violist Tabea Zimmermann and pianist Itamar Golan, the programme including Bloch’s suite for cello and piano ‘From Jewish Life’. Afterwards, a man radiating charisma, with a beautiful voice, hands and eyes, smoking heavily, and accompanied by his much-younger partner (the pianist Ana-Maria Vera), came backstage. ‘Sometimes people’s playing speaks to me,’ he said (or words to that effect) ‘and that’s what happened tonight’. (Touchingly, he remembered that concert for the rest of his life.) So of course – I adored him from that moment on! But it was only a few months later, when he gave a recital with Ana-Maria at the Wigmore Hall, that I truly fell under the spell of his genius. They played the Kreutzer sonata in a way utterly unlike any reading of that work that I’d ever heard. Ivry’s playing had more character per square note than many other musicians put into a whole performance; the audience was swept away. Even that concert wasn’t without its share of controversy, however – it wasn’t in Ivry’s nature! At one point he heard – or fancied he heard – a noise going on backstage. He stopped mid-phrase. ‘What’s that?’ he demanded to know, looking at us, the audience, accusingly. A shocked silence from the auditorium. He folded his violin under his arm. ‘Good – so I don‘t have to play,’ he said. Voices now rose from the audience, people begging him to continue. Eventually he relented, and went on – with no loss of concentration. It was all part of the Ivry experience, somehow. After the concert, he took Nigel Kennedy – at that point a huge fan too – and me back to his hotel for dinner and party-time. I remember that at one point he hugged both Nigel and me to his sides – and practically broke our necks! He was strong, to put it mildly.

After that, I invited both Ivry and Ana-Maria to Open Chamber Music at Prussia Cove, where Ivry inevitably changed the atmosphere of the whole seminar. Again, some people failed to ‘get’ him, while others adored him. Nobody could ever be indifferent! I loved spending time with him, of course, hearing his magical stream of Jewish jokes, commentaries on life, epithets, etc. We also played together for the first time, Beethoven’s Archduke trio with Ana-Maria – though I have to admit that it was not any of our finest hour. In fact, Ivry and I only performed together three times: after that, we played Mendelssohn’s D minor trio with his fiercely loyal friend and partner Martha Argerich, and then the Tchaikovsky trio with Nelson Goerner. Of course, it was wonderful to play with him and Martha. The Tchaikovsky was more – surprise, surprise – controversial. It was at the Wigmore Hall, as part of a series of Russian chamber music. Ivry had learned the piece specially. I thought he played it marvellously, although – needless to say – unconventionally. Others didn’t agree; for perhaps the only time in all my hundreds if not thousands of times onstage or in the audience at the Wigmore Hall, there was a loud ‘boo’ at the end. I was shocked – though perhaps not quite as shocked as the poor presenter for the live BBC broadcast, who had to keep on with her post-performance announcements, ignoring the hooligan outburst. Was the boo justified? No, it was not. Ivry played the trio exactly as he saw it, as he felt it – and one could take it or leave it. It was absolutely genuine, and riveting; the actor Simon Callow described it as being like a shaman telling stories from the deep past. (The mixed reactions mirrored those to another hero of mine, Daniil Shafran – whom Ivry never met, but to whom he somehow felt close.)

Anyway, I don’t want to linger too much on negative reactions to Ivry. He had a huge army of people who loved and adored him – including, among pianists, Martha, of course, and many others, including Khatia Buniatishvili, Stephen Hough, Olli Mustonen and Itamar Golan, and countless string-players such as Maxim Vengerov, Janine Jansen, Renaud Capucon, Richard Tognetti, Heinrich Schiff and Mischa Maisky. (And even conductors, although you needed a strong nerve to accompany him in a concerto! Some people, such as Paavo Jarvi, managed it, though.) These people didn’t just like Ivry – they truly loved him. Once you got the Ivry bug, no medicine could cure you of it – and you didn’t want to be cured.

Of course, Ivry got older – and older; but his spirit didn’t! Once I was sitting with him at the Eurostar terminal, meeting for a coffee before he was to take the train back to Paris. We talked and talked (as usual) – and then he suddenly looked at his watch. ‘Eh merde! I’m late to meet the man with the wheelchair!’ And off he dashed, with me in hot pursuit, trying to warn him that it might not be the best idea to arrive that way to pick up his wheelchair! (He’d only wanted it as a convenient way of carrying his luggage). His 90th birthday was celebrated in style, with big concerts in Paris (which I missed) and Brussels, in which I was honoured to take part, along with a wonderful group of musicians paying homage to him – and playing with him, as well as for him. The concert started late and went on for hours, followed by a dinner. I think that we left around 2.30 am – leaving Ivry still in full throttle.

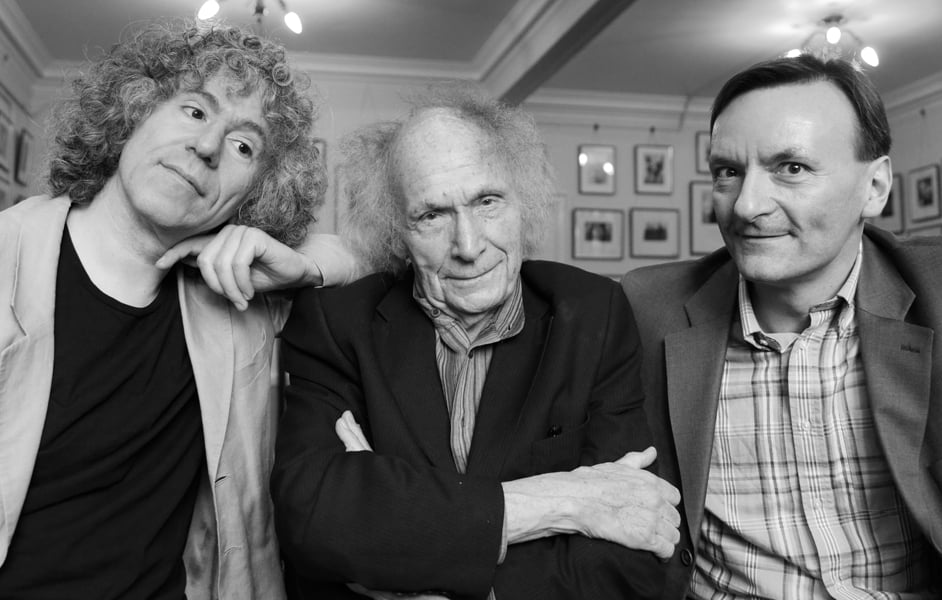

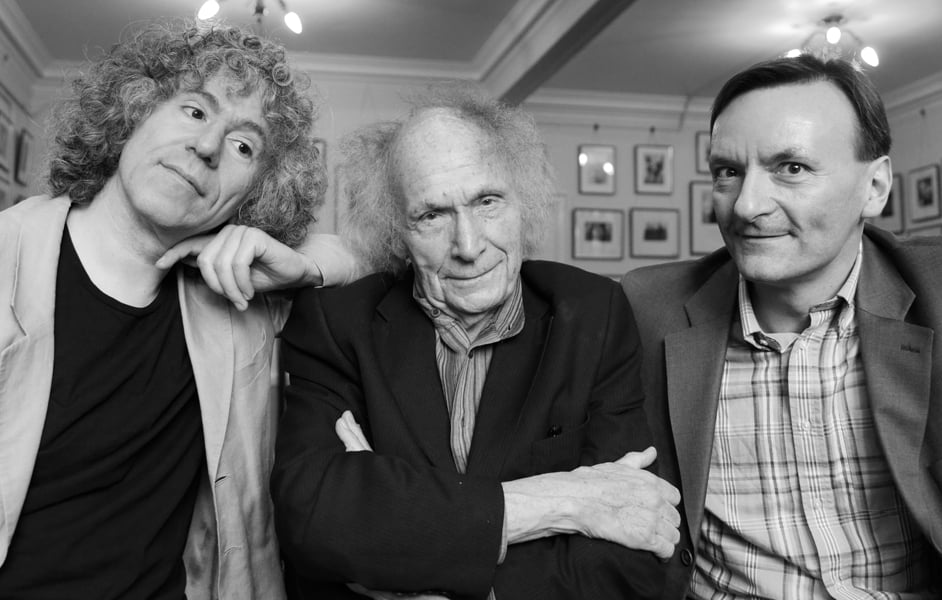

Around the same time, I got to interview him at the Wigmore Hall, for an hour and half or so during which he shone, peppering the whole occasion with his characteristic blend of wisdom, wit, repartee, anecdote and frippery. (Luckily the talk was filmed; the video has vanished from Youtube, unfortunately, but I hope it’s going to be put up again soon.) At the end of the interview, Ivry took up his violin and played three of his favourite little pieces, with Stephen Hough accompanying him, entirely without rehearsal. Most of the audience was in tears. (The pictures below were all taken by Joanna Bergin on that day.)

Eventually, though, even Ivry became old – in body, anyway. Last time I saw him was just over a year ago, at his extraordinarily messy and wonderful apartment in Paris. He was ailing, and on two of my three visits was in bed. (On the third occasion, he was sitting up at a table having some dinner. ‘Oh good – you’re up!’ I exclaimed. He looked at me rather witheringly. ‘It’s a bit hard to eat in bed,’ he responded.)…

But then he just couldn’t stay on in the apartment (which was only reachable by means of some steep, dark stairs); and he was taken to a clinic. He was pretty miserable there, I have to admit – above all from loneliness: ‘Here I am, at the end of my life, all alone.’ Ivry couldn’t stand to be by himself. Nevertheless, there were still brighter moments, particularly when his loyal friends visited, or at least called; and he was still very much Ivry, right up to the end. Once he sounded brighter. ‘You sound good!’ I said. ‘Well, I’m noted for my good sound,’ he replied. We talked every few days; he never lost his typical Ivry tone of indignation. ‘Call me sometime!’ he’d demand indignantly. ‘I’m calling you now,’ I’d point out. ‘Yes, I know you are’ he’d admit, somewhat mollified. It wasn’t that long ago – maybe three months? – that he was suggesting that he, Martha and I put on a series of short trio concerts; and not long before that he’d berated Ana-Maria for not inviting him to Bolivia!

So he didn’t give hope – at least, not till very near the end. Even then, there were moments: a few weeks ago I called (or rather Facetimed, which was how we mostly spoke), and a young violinist-student of Itamar’s was playing to him, which was evidently pleasing him; then, just 2 ½ weeks ago, I called, and he was positively bright. ‘You seem so much better!’ I exclaimed. In reply, he just pointed the phone-camera to the other side of the room: Martha was visiting him.

But now he’s gone. Or at least, gone from this planet. It’s impossible to believe that he’s really vanished – a spirit like his is surely unquenchable? At the very least, he leaves us with precious memories of him (as well as, thank goodness, wondrous recordings) – of his irresistible personality, his gloriously fiery playing, of the love that he inspired and radiated. Thank you, Ivry.

Isserlis, Gitlis, Stephen Hough, photo: Joanna Bergin