My next essay for The Critic has yet to go online but I’ll offer you a taster of why Alex Ross’s brilliant new book Wagner-ism places us even more firly in diametrially opposed camps.

Wagner divides his audience between those who want to go on afterwards to dinner, and the rest who want to invade Poland. The most inflammatory composer that ever lived, he was an atrocious man of irresistible magnetism, a disrupter who left blood in his wake. One of my schoolteachers, a Hitler refugee, introduced him as follows: ‘Richard Wagner, may his name and memory be erased for ever and ever, was (deep sigh) a verrry great composer.’ That says it all.

As a child, taken by my stepmother to see her favourite opera, I could not work out why a young woman had to sacrifice her life for the flying Dutchman to find a bit of peace. At the Metropolitan Opera, I saw my watch tick past one a.m. as James Levine dragged us through that para-Christian rite known as Parsifal. Life, mine at least, can feel too short for Wagner.

I have survived four rounds of the Ring, been mesmerized by Meistersinger, stupefied by the longueurs of Lohengrin. The one that gets me every time is Tristan und Isolde which suspends the resolution of a chord for almost four hours, the longest delayed ejaculation in canon.

In awe of such tantric feats, I made a pilgrimage to the shrine – only to declare Bayreu-xit on seeing the old wangler’s descendant still running the show for the benefit of Angela Merkel and the German elite. At Bayreuth I felt, for the first time, physically soiled by art. This year, the onset of Covid-19 left no Ring-shaped hole in my soul.

That puts me in the opposite camp to the New Yorker critic Alex Ross, whose monumental new book, titled Wagner-ism maintains that Wagner was ‘the most widely influential figure in the history of music’ – possibly an even greater influencer than the actor Stephen Fry who shouts ‘miraculous’ on the book’s cover, thereby placing it beyond reasoned discussion….

If you want to read more, you’ll have to buy The Critic at a newstand, or wait til the full article goes online in the next few days.

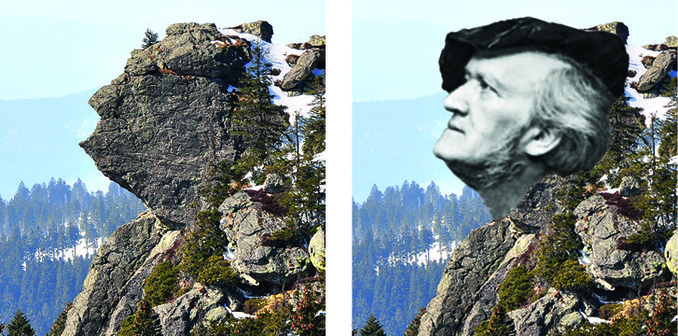

Look, he even shapes nature.