The posture has not changed.

The posture has not changed.

Forever Karita,

Welcome to the 113th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Symphony No. 9 in D minor op. 125 (part 6)

(1 How Beethoven wrote it here. 2 How the world changed it here. 3 How do you choose a Ninth here. 4 Furtwängler or Karajan here. 5 The Beethoven 9th that stopped the world here)

We are down to the wire. From almost a century of recordings and 150 versions, I am about to whittle down the list to a manageable dozen.

Inevitably, personal experience conditions my choices. The first Ninth that I attended was, I think, with Otto Klemperer, though I may only have seen him on television. Whichever it was, the impregable figure of Klemperer looms large in my early consciousness and the sound that he conjures at the opening of this 1960 recording possesses such authority that, once heard, one cannot imagine it being done in any other way. The Philharmonia Orchestra sounds more German than British and the presence of the short-lived Fritz Wunderlich among the soloists is enough to give this production everlasting status.

My next experiences were at the Royal Albert Hall, mostly BBC Proms, with the phenomenal pack of chief conductors that London had in the 1980s – Claudio Abbado, Klaus Tennstedt, Georg Solti, Bernard Haitink. The storm and release of a Tennstedt performance is not easily described, nor was it captured faithfully on record, as the EMI editors liked to tinker about and leave things all neat and tidy before they put a record on the market, but I am glad that something survives of this most dramatic and appealing of conductors.

Georg Solti’s Chicago recordings require no recommendation. The choice is between 1972, when he was new to the city, and 1987, when he was starting to tire. The later performance, on the other hand, has Jessye Norman. I’m still sticking with 1972: big, brash and unexpectedly beautiful in the strings.

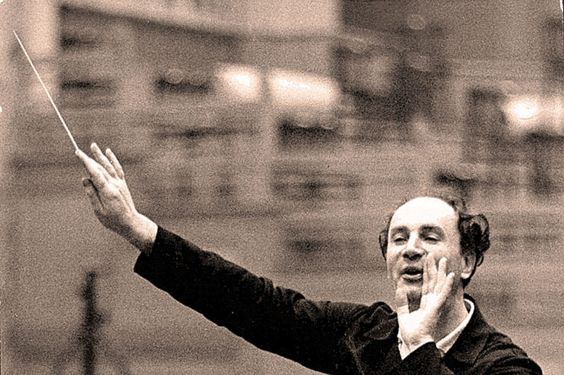

The question people keep asking is, why did Carlos Kleiber not attempt the Ninth when he so comprehensively conquered the fourth, fifth and seventh symphonies? There is no answer to this condundrum except to refer you to the 1952 recording of the Ninth made by his father, Erich Kleiber, in Vienna. Carlos modelled his technique and repertoire on his father’s. If he could not do better than Erich, he ducked out of the contest. The Erich Kleiber recording is exquisitely shaped, just a volt or two short of combustion. Watch his classic long-baton technique in this rare filmed document from the 1949 Prague Spring (the singing is atrocious, the female chorus visibly under-nourished).

Many Americans my age swear by Arturo Toscanini, even though they know him only on record. If it’s voltage you want, Toscanini owns the electricity board. The excitement can be breathtaking. But both of his NBC orchestra recordings in 1939 and 1952 are maimed by wretched sound. His return to La Scala in 1946 after a decade of exile has cathartic qualities and a numinous dimension.

If the name René Leibowitz rings a bell, you are a certified record freak and should seek treatment without delay. The son of Russian-Jewish refugees, Leibowitz played piano in Paris jazz clubs until he discovered Arnold Schoenberg and converted to ascetic modernism. Teaching the post-War German composers at Darmstadt, he reinvented himself as a conductor and landed contracts from various record companies, including – believe it or not – the Readers Digest, which wanted an affordable Beethoven set that would not frighten the horses in Pleasantville.

Leibowitz was scoffed at for pandering to lowbrows, but his performances with Beecham’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra are altogether very good and, in the ninth symphony, overwhelming. Eminently civilised, almost understated, he builds a tension not unlike Karajan’s but less threatening and with a deep empathy with Beethoven’s language. The American musicologist Richard Taruskin finds his performances more authentic than a historically informed performance (HIP) specialist such as Christopher Hogwood.

I shall deal briskly with the HIPsters. John Eliot Gardiner and L’orchestre Revolutionnaire et Romantique (1994) are too fast, too noisy, too rough-and-tumble. Roger Norrington is more reasoned, rounded, less in-your face with the London Classical Players (1987) and borderline beautiful with the Stuttgart radio orchestra (2000). Nikolaus Harnoncourt has the best of both worlds with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe (1991), early pitch and tempo on modern instruments, but his tempi could be tauter. David Zinman applies some period practices in his fine 1999 Zurich account. Which would Beethoven have chosen? Probably the loudest, largest orchestra.

Entering the 21st century, I am more impressed by Simon Rattle with the Vienna Philharmonic (2002) than with his Berlin repeat in 2016. Mariss Jansons (Munich 2007) and Mikhail Pletnev (Moscow 2007) represent the Russian Beethoven tradition without challenging the centrists. Riccardo Chailly gives an exceptionally refined performance in his Leipzig cycle (2011) while Christian Thielemann keeps to the middle of the autobahn (Vienna 2011). Among recent attempts, I find much to like in Philippe Jordan with the Vienna Symphony (2017) and much promise in Andris Nelsons with the Vienna Philharmonic (2018).

In 2019, the year of his retirement, the 90 year-old Bernard Haitink gave a valedictory Beethoven’s 9th with the Bavarian radio orchestra. Once a workhorse of the record studios, Haitink had mellowed into a repository of several traditions – Dutch, German, French and English – delivering a blended Beethoven that, while globalised, was at all times, intensely personal and heartfelt. The Adagio may not be as sleek as his younger performances but the finale is full of compassion, comprehension and human transmission, a reading to treasure.

I wrote early on in this survey that a conductor needs to understand and empathise with Beethoven’s circumstances before he or she can grasp the ninth. The performance I have kept to last is Rafael Kubelik‘s (Munich, 1975), the work of a Czech musician who endured the German occupation of his country, fled the Communist regime, recoiled from American conservatism and finally dedicated himself to creating a world-class ensemble in Bavaria. Kubelik knew tragedy and deprivation in his life yet always maintained a Beethoven-like faith that tomorrow might be a better day. He assured me in 1982 that Communism would fall one day and he would return home. In 1990, he did. His Beethoven ninth is full of that irrepressible belief in a brighter future. I can never hear it without thinking he might be right.

So, my selection of indispensable Beethoven 9ths runs like this:

Wilhelm Furtwängler, Berlin 1942

Jascha Horenstein, Vienna 1956

Otto Klemperer, Amsterdam 1956

Ferenc Fricsay, Berlin 1957

George Szell, Cleveland 1961

René Leibowitz, London 1961

Herbert von Karajan, 1962

Georg Solti, 1972

Rafael Kubelik, Munich 1975

Klaus Tennstedt, London 1992

David Zinman, Zurich 1999

Riccardo Chailly, Leipzig 2011

Bernard Haitink, Munich 2019

Too many, I know. If I had to choose one to save my life? Fricsay.

Or Kubelik.

In his first cull of top management, the new BBC DG Tim Davie has cut the management board from 17 to 11.

Among those toppled is James Purnell, 50, Director of Radio & Education.

A former Secretary of State for Culture under Gordon Brown, Purnell was among exDG Tony Hall’s earliest recruits and closest advisers.

Since it would be irrational to exclude radio from the BBC’s top table, one has to assume that the demotion is personal. If so it bodes it for Purnell’s pup Alan Davey at BBC Radio 3 and for his embattled Proms director David Pickard. Several BBC head will now sleep less easy.

Hallfríður Haffi Ólafsdóttir, principal flute of the Iceland Symphony Orchestra, has died of cancer. She

trained at the Royal Academy of Music in London and was widely admired and loved.