Late in his own life, when he had recovered the use of both hands, Fleisher gave an incomparable account of Schubert’s late sonata.

Late in his own life, when he had recovered the use of both hands, Fleisher gave an incomparable account of Schubert’s late sonata.

We have been notified of the death, after a long illness, of Wolfgang Glüxam, a respected Austrian harpsichord and organ specialist, professor at the University of Music in Vienna.

At Yale, all of music terminology is now considered racist. Read this latest musicological effusion:

Call for Papers: Deadline September 30

Key Terms in Music Theory for Anti-Racist Scholars:

Epistemic Disavowals, Reimagined Formalisms

Edited by Jade Conlee (Yale University) and Tatiana Koike (Yale University)

[Formalism, we should point out, was first used as a music-critical term by Joseph Stalin. NL]

How much do formalisms, and words themselves, remember of their problematic pasts? Music theory’s foremost contribution to music studies in the West is its analytical terminology; this vocabulary facilitates detailed discussions of musical surfaces across disciplines.

Nevertheless, the central claims and innovations of canonic theorists

such as Heinrich Schenker and Hugo Riemann root our basic descriptive concepts in

an intellectual lineage of elitism, eurocentrism, colonization, patriarchy, and ultimately

white supremacy. Terms such as pitch, scale, analysis, and work thereby coproduce a

musical formalism built around the affordances of the Enlightenment subject. These

historical issues are made particularly salient by the recent “Global Turn” in music the-

ory, which seeks to decenter the Western canon by demonstrating the commonality of

musical patterning across cultures. Present-day globalists share with nineteenth-centu-

ry theorists a belief in cross-cultural musical formalism, albeit one put toward differing

ends. German nationalist theorists used formalism to naturalize globalized ethnic and

racial power imbalances, infantilizing the music of other cultures in order to justify the

superiority of Western art music in ways that present-day theorists do not. Yet, when

present-day globalists deploy the same formalisms to draw comparisons across the mu-

sics of different cultures, the result is often an implicit disavowal of the power imbal-

ances nineteenth-century theorists so ardently upheld. This disavowal persists because

the transfer of music-theoretical formalism and its historico-ideological context from

German nationalism to American globalism largely remains uninterrogated. Can we

instead directly address the constellation of class, culture, race, and power that grounds

our discipline’s methods of knowledge production and presumed aesthetic objects by

redefining the formalisms music theory employs? Scholars in disciplines such as jazz

studies and critical race theory, for instance, have reclaimed formalism as a way of

critiquing and transcending the epistemic injustices that minority groups have faced

in Western cultures. Is it possible to redefine our theoretical vocabulary, formalizing

music in ways that embrace alternative theories of the subject and models of history?

Our volume takes up an anti-racist reimagining of music-theoretical formalism by ex-

amining the ideologies latent in the discipline’s foundational terminology. In a recent

blog post, music theorist Philip Ewell observes, “with respect to racial and gender mat-

ters, music theory—and the white-male frame generally—only recognizes linear time:

‘that was then and this is now, we don’t have the same problem with racism and sexism

that they did then, so stop talking about it.’” Like Ewell, we hold that to shift the field

of music theory toward an anti-racist praxis, we must first look backward in order to

move forward. We might find a model for such work in ethnomusicology’s postwar

examination of their field’s roots in nineteenth-century German comparative musicol-

ogy—an intellectual environment shared by many of the theorists whose work we wish

to revisit in this volume. The present compilation draws from ethnomusicology’s anal-

ysis of power relations and the academic gaze by asking how the West’s colonial history

and internal dynamic of white supremacy continue to color the claims music theo-

rists make about repertoires both inside and outside the Western art music canon. Al-

though revetting music-theoretical primary sources will complicate our relationships

with many of the field’s historical figures and concepts, such an undertaking also has

the potential to broaden the discipline, rendering music-theoretical topics accessible to

scholars passionate about race- and class-based analyses of intellectual history, media,

and aesthetics.

We are seeking short essays (ca. 6000 words) that think critically about one key term

in the discourse of Western music theory. Each contribution should cite important

moments in the term’s discursive history that bear on its usage in present-day music

studies. We then invite authors to think creatively about how such a history can inform

a critique of the discipline and offer a vision forward. Some questions authors might

consider in their essays include: How do these terms participate in producing musi-

cal ontologies that overdetermine the superiority of Western art music? What kinds

of idealized listening practices do these terms prescribe, and what types of listening

subjects do they take for granted? How might these terms operate in a new and specu-

lative formalist framework? We have chosen a key-terms format so that the volume

may serve as a teaching tool for advanced undergraduates and those new to the history

of Western music theory while also remaining relevant to advanced scholars in music

studies across disciplines. We welcome submissions from scholars at all career stages

and coming from any discipline, including music theory, ethnomusicology, popular

music studies, jazz studies, sound studies, and historical musicology. Authors may sub-

mit proposals on terms from the list below or may propose a term not included in this

list. Please submit a 400-word abstract and brief biography to jade.conlee@yale.edu by

September 30, 2020.

List of Key Terms

Form Form

Pitch Ton, Stufe, Klang

Tonality Tonalität

Scale Tonreihe, Tonleiter, Skala

Key Tonart, Schlüssel

Work Werk, Meisterwerk

Cadence Schluss, Kadenz

Analysis Analyse, Reduktionsanalyse

Phrase Satz

Melody Stimme, Melodische Führung

Heterophony Heterophonie

Polyphony Polyphonie, Mehrstimmigkeit

Harmony Harmonie, Akkord, Klang, Dreiklang

Harmonic Function Funktionenlehre

Consonance Konsonanz

Dissonance Dissonanz

Polyrhythm Polyrhythmik

Meter Takt

Notation Notenschrift

Chord Progression Zug, Harmoniefolge

Musical Structure Ursatz, Hintergrund, Musikalische Logik

From Texas Classical Review:

The Dallas Symphony Orchestra announced on Friday that it will present a “carefully curated” fall season of short concerts with smaller ensembles playing to a maximum audience of 75 people per performance.

A revised fall season at Meyerson Symphony Center — which normally seats 2,602 people — begins on September 4 and marks the debut of Fabio Luisi as DSO music director after a season as interim music director. A Verdi specialist, Luisi will conduct a pared-down orchestra and four vocalists in a set of Verdi favorites (October 29-November 1), and will lead programs featuring Beethoven (September 10-13) and Mahler (October 9-11). Classical programming dominates the calendar, with forays into jazz and Ragtime (September 18-20) and soul (November 13-15)….

More here.

It’s coming home, it’s coming home….

This was Noah Max and his Echo Ensemble, suitably distanced in North Square, Hampstead Garden Suburb. Grieg, Purcell, Vaughan Williams, Bartok, John Barry and two pieces by Noah himself.

Andrè Schuen, who’s singing Guglielmo in the Salzburg Così fan tutte, has got himself a Yellow Label contract.

He’ll launch with Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin next spring.

… and his fellow cast-members of Naples’s Aida.

From Kaufmann’s fanclub feed.

The indefatigable Leon Fleisher, who has died aged 92, may have been the greatest American Brahms interpreter.

As a Schnabel student, he penetrated Beethoven with ease and illumination, especially the G major concerto which he played as if Schnabel was listening outside the door.

He was an exemplary teacher.

He taught us how to cope with adversity.

He had his own way with Bach.

And he made Hindemith sound almost sexy.

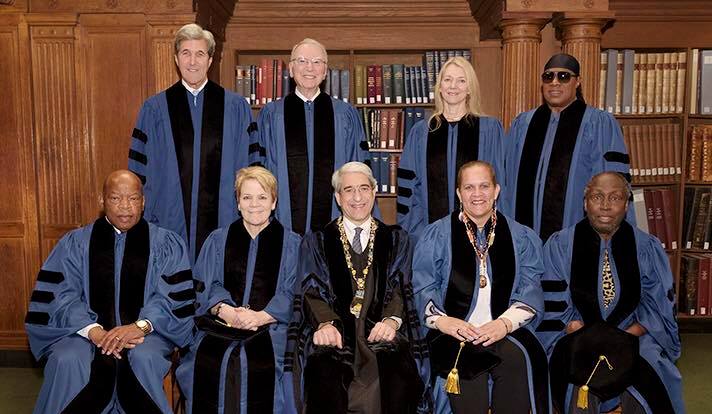

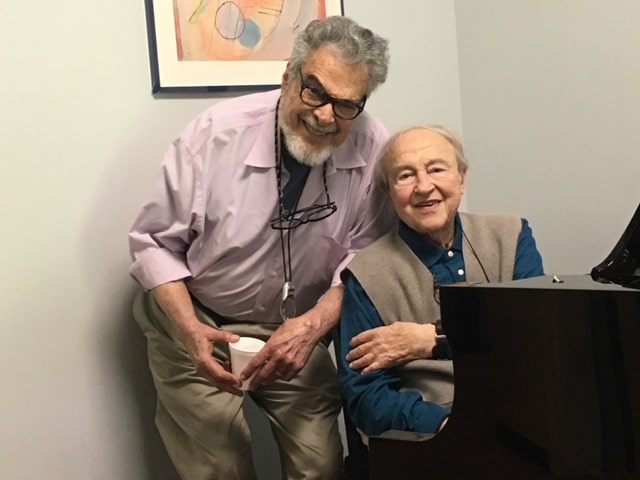

With Menahem Pressler, 2016

The universally admired, effortlessly influential Leon Fleisher has died at 92.

An Artur Schnabel disciple, he taught generations of Peabody students in Baltimore the human way of making music. When his right hand was disabled by focal dystonia, he continued his performing career as a left-hand specialist, popularising the concertos that had been written for the First War victim Paul Wittgenstein.

Conductors, musicians and audiences alike appreciated his composed presence on stage. He made numerous, indelible recordings and was truly loved.

Fleisher remembers:

I came to the attention of the then conductor of the [San Francisco] Orchestra, a Frenchman, Pierre Monteux. The conductors knew and respected one another; they were friends. They agreed that I needed, what you would call it, “world class instruction.” And they were both good friends of Artur Schnabel, who was one of the great figures of the 20th century in music, who would come out to San Francisco every two, three, four years and play. Both Monteux and Hertz got in touch with Schnabel, told him about me, and he very discreetly declined, saying he never accepted anybody under 16 for language reasons. He spoke in great abstractions in terms of concepts. I was 9.

As it happened, in the spring of ’38 he came out to San Francisco to play, and had dinner with the Hertzes. They snuck me in through the basement, so when they opened the dining room doors, this kid was sitting at the piano. Being a gentleman, Schnabel resigned himself to the inevitable, so I played for him. I played a Sonetto del Petrarca of Liszt, the third one, and I played the cadenza from the Beethoven B-flat Concerto. I didn’t hear it happen, but he apparently accepted me because he invited me to join him that summer in his home in Lake Como of all places, long before George Clooney moved there…

I worked with him for 10 years. Whoever got the idea that a musician’s education should be the equivalent of liberal arts—four years undergraduate, two years for your master’s—utter nonsense. He taught quite differently than other teachers, and I’ve adopted that for my own ways. He had only a small handful of students, and he requested that all students be present for everybody’s lesson. If there were five students, you learned five times the repertoire. And you saw how we all shared the same challenges. It gave you an overview, and you began to realize that like there are laws of physics, there are laws of music in a way. A lot is made of the relationship between music and math, which I think is comparatively superficial. The real connection is between music and physics. Music is movement. Music passes in time from point A to point B. And because it’s movement, it’s subject to all the laws that govern movement.

More follows.