He’s in a Buenos Aires piano bar in August 2014.

He’s in a Buenos Aires piano bar in August 2014.

Welcome to the 93rd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Beethoven: Piano sonata no 30, opus 109

Composed in 1820, this the first of three sonatas written in quick succession in which Beethoven concludes a genre that he has taken from elemental Mozartian entertainment to a summit of musical thought. The landscape he has crossed is continental. If his first sonata is light-years away from this pre-penultimate peak, so too is the distance from its immediate predecessor, the Hammerklavier. Every step Beethoven now takes is measured in giant’s boots.

The sonata opens with deceptive, seductive simplicity, much of the melodic work being given to the right hand at the top of the keyboard and the left having little more to do than chant Amen. But there is more going on than meets the ear. Beethoven is in poor health after an attack of jaundice but in high spirits after a court has granted him irrevocable custody of his nephew, to the exclusion of the boy’s mother. He is starting to think of a great Mass of thanksgiving – the Missa Solemnis – and the apparent simplicity of his expression deepens into a quite unexpected moral contemplation. He is writing in his happy key, E major, but he drifts over to B and then the remote D-sharp major. It is impossible at first sight to tell where he’s going.

The opening movements last just three and two minutes each, blink and they are gone. But the finale is a 12-minute set, opening with a theme of profound thanksgiving and giving way to six of the most ambitious variations ever attempted on the keyboard, all of them in E major (as if he’s trying to prove that it’s possible). There’s a singing quality to the second variation and a hint of angels in the third. In and out of the texture, we hear anticipations of the Missa Solemnis. This is not piano music: it is the gateway to heaven.

Beethoven wrote a dedication to Maximiliane Brentano, daughter of his sometime Frankfurt agent, and now all of 19 years old. It is no ordinary dedication but an attempt to raise the young woman, and himself by associatio a feeling of kindnessn, above mundane existence to place them both in a higher realm of spirituality. Read this:

A dedication!!! Well, this is not one of those dedications that are used and abused by thousands of people. It is the spirit which unites the noble and finer people of this earth and which time can never destroy. It is this spirit which now speaks to you and which calls you to mind and makes me see you still as a child, your father imbued with somany truly good and noble qualities and ever mindful of the welfare of his children… The memory of this noble family can never fade in my heart. May you sometimes think of me with a feeling of kindness. My most heartfelt wishes. May heaven bless your life and the lives of all of you forever. (transl. Martin Cooper).

The aspiration to an ideal family is clearly linked to concerns for his destabilised nephew; the rest seems to mark the beginning of a farewell to the earthly world and an embrace of eternity. Beethoven starts leaving us in the opus 109. It is truly hard for an interpreter to keep the work well grounded. Few attempted the score in Beethoven’s lifetime. It was Franz Liszt in the 1830s who brought it onto the concert stage.

Two modern pianists have made this work their calling card and receuved accolades from the general consensus of critics who cluster around niche record magazines. Of the two perfomers, I am drawn more to Alfred Brendel in this sonata than to Maurizio Pollini. Brendel talks and writes a lot about the cogitation that he invests in performing a work of this magnitude, but when he comes to play one hears nothing but lightness – perhaps less so in his early Vienna cycle of 1962-64, but most enchantingly a decade later in his Philips set. Pollini, to my ears, displays mental agonies of preparation in both of his DG recordings.

The featherlight pianist in this piece is Friedrich Gulda(1958), daringly hushed, irresistible and incontrovertible in Beethoven of all types. I am also much taken by the unflappable Maria Joao Pires (2001), who allows complexity to emerge unnoticed from the text. Some will find Glenn Gould (1956) intolerably prosaic, with jazzy little riffs in his opening phrases and a sense that he could play this sonata with at least one hand tied behind his back. Gould fans maintain that his approach grows on you with time. I’m still waiting.

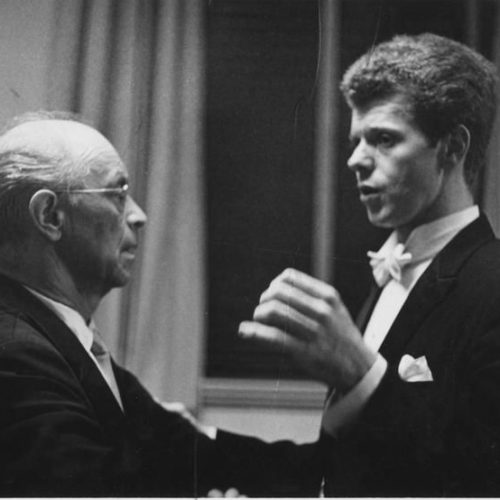

I have similar prejudices against the fake restraint of Andras Schiff (2007) in the opening phrases, an intimation that he’s holding something back for one reason or other. Schiff is a marvellous pianist with strong technique and a combative mind; restraint does not suit him (or maybe it’s me). Rudolf Serkin (1987), in a rare European recording, delivers a masterclass in almost-late Beethoven, introducing a man who is on the threshold of immortality yet speaks in a language all can understand. This, for me, is one of Serkin’s summits, and in pristine sound. The closing bars are simply celestial.

The Scottish pianist Steven Osborne (not on Idagio) comes high on my list with an uncluttered directness; likewise Angela Hewitt on the same Hyperion label. Mitsuko Uchida (2006) deserves to be on every shortlist. Her storytelling is altogether individual, her breathing unlike any other pianist’s. Backhaus and Schnabel come into my reckoning, along with Arrau, Gilels, Richter – eliding half as many notes as he plays in the opening, overwhelming in the variations – and the quietly poetic Solomon Cutner (1953).

Final choice? Brendel and Serkin are essential listening.

Rudolf Serkin (l.) with Van Cliburn

Glad to see that the enterprising Grange Park Opera has dipped into the next generation.