Mahler’s darkest hour.

Mahler’s darkest hour.

Welcome to the 87th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

In addition to the five numbered piano concertos, sketches exist for two more. The larger outline was written when Beethoven was 13 or 14. After multiple revisions, he seems to have forgotten about it once he left home for Vienna, probably recognising that it was a few paces behind the leaders. The solo part is fully sketched and there are indications for orchestral accompaniment. The manuscript sits in the Berlin State Library, where a number of pianists have studied it prior to making recordings. Scholars duly accorded it the numeral zero, as if it were a respectable work in the catalogue.

Is it? Not really. The opening theme is like juvenile Mozart without the wit and sideswipes. Beethoven develops his little tune in a conventional fashion, as if he were preparing homework for his teacher, and the general effect is of a score by one of his less interesting contemporaries – Clementi or Dussek or even Czerny – note-spinning to no lasting purpose. The second movement gives hints of what might lie ahead in the C major and D major concertos, but the notes tickle the ear without gripping it. The whole work in its most augmented form lasts 23 minutes and you’d be hard-pressed to remember any of it an hour later. Mari Kodama gives an agreeable reading in 2019 with her husband, Kent Nagano, conducting the DSO-Berlin. Ronald Brautigam made a rather fuller orchestration for his 2008 recording on BIS, playing a period piano with massive flourish. There is also a recording by Howard Shelley that I have not been able to find.

The chief alternative to Kodama is Sophie-Mayuko Vetter, a Japanese-German pianist who is closely associated with Stockhausen-type modernism. Vetter plays a Beethoven-era Broadwood fortepiano and sounds fully committed to this material. She is accompanied by the Hamburg Symphony Orchestra, conducted a tad pedantically by Peter Ruzicka. She adds an intriguing world premiere of…

Beethoven Rondo for Piano and Orchestra in B-flat major B-flat major, WoO 6

This is another piano concerto fragment, published posthumously in 1829 with the solo part completed by Carl Czerny. The orchestration was reconstructed in 2018 by Nicholas Cook and Hermann Dechant. What catches the ear is a hint of the opening phrase of the future Emperor Concerto. Could that be possible? With Beethoven, everything’s possible. Vetter plays with panache and conviction.

Concerto for Pianoforte and Orchestra in D major op. 61a

After the chaotic premiere of Beethoven’s violin concerto, which was poorly received, Muzio Clementi asked if he could make a version for piano. Beethoven consented and the alternative version appeared in 1807. Beethoven was sufficiently enthused by Clementi’s effort to write a new cadenza for the first movement, involving plenty of percussion as well as solo piano.

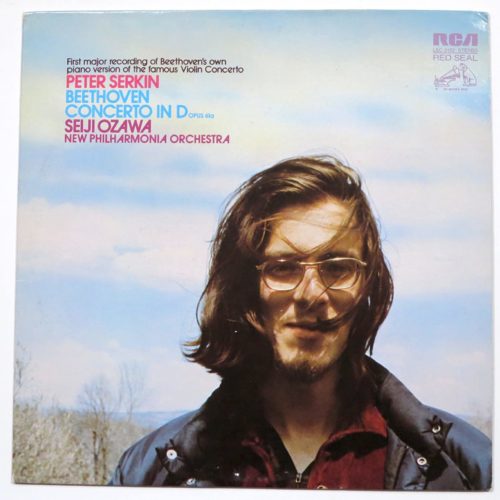

There have been a number of recordings, some of quirkish disposition. I rather like Peter Serkin in his hippie period playing the concerto with Seiji Ozawa and the New Philharmonia. The tempi are a bit sluggish and the orchestra is too far recessed for comfort, but Serkin gives the work a subversive twist, ambling his way into it as if he’s not sure whether he should be doing this square stuff at all, but growing to like it despite himself. Certainly, it is the least awkward of all the versions I have heard – and all of them leave me squirming to some extent since the towering existence of the violin concerto looms over anyone who attempts this ersatz piano swap.

An especially intriguing offering on Idagio is a 1954 Vienna performance by Helen Schnabel, Arthur’s daughter-in-law, and on this evidence a capable if not overly characterful keyboard artist. The orchestra is unnamed but the conductor is F Charles Adler, a pioneering Mahlerian, and his control of the proceedings makes this a worthwhile and immersive experience. There are moments of near-rapture in the adagio, which is more than we have a right to expect in a secondhand score. I’d like to hear more of Ms Schnabel.

Other contenders include the Finn Olli Mustonen, directing the Tapiola Sinfonietta with a heavyish hand, paying too much homage to the work’s reputation to make it credibly his own. The Frenchman Francois-René Duchable has a different problem with the Warsaw Sinfonia. His conductor is Yehudi Menuhin and no way is Yehudi going to let a pianist seize control of a summit of violin lore.

My first encounter with opus 61a was in Daniel Barenboim’s 1989 recording for DG with the London Philharmonic. I disliked it on first hearing and find even greater fault with it now. Barenboim conducts from the keyboard, reducing the solo part to little more than tinkling decoration and seriously undermining the balance of the work. Beethoven intended the violin to engage in mortal combat with the orchestra. Barenboim reduces the impact to that of a middling Mozart piano concerto, nothing grandiose about it.

Peter Serkin and Helen Schnabel are the ones to sample, secondary names of famous brands.

The young American conductor Christopher Quentin McMullen-Laird has died of an unspecified medical issue.

Music Director of the Jæren Symfoniorkester in Norway, he was previously assistant to Kent Nagano and Kirill Petrenko at the Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich.

Christopher was a Leverhulme Arts Scholar at the Royal College of Music London where he earned a Master’s of Music in Conducting, following a Bachelor’s degree at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire.

You can read tributes in his memorial page here.