Welcome to the 73rd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Piano sonata No. 23 in F minor op. 57, ‘Appassionata’ (1804)

Three times as many pianists have recorded the 23rd sonata as those who performed the 22nd. The so-called Appassionata took off in public esteem when a publisher gave it the present title, a decade after Beethoven died. Among its ardent fans was the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, who told Maxim Gorky: ‘I know nothing that is greater than the Appassionata; I would like to listen to it every day. It is marvellous, superhuman music. I always think with pride – perhaps it is naïve of me – what marvellous things humans can do.’

What we know of its composition is that Beethoven dreamed it up while taking daylong walks in the Vienna Woods, near Döbling, in July 1804. His pupil Ferdinand Ries recalled: “We went so far astray that we did not get back to Döbling until nearly 8 o’clock. He had been humming, and more often howling, always up and down, without singing any definite notes. When questioned as to what it was he answered, ‘A theme for the last movement of the sonata has occurred to me.’ When we entered the room he ran to the pianoforte without taking off his hat… He stormed for at least an hour with the beautiful finale of the sonata. Finally he got up, was surprised that I was still there and said, ‘I cannot give you a lesson today, I must do some work’.’

The opening movement contains the arresting motif of the fifth symphony. The central passage throbs with mischief and yearning. The finale is a race through the woods, perhaps a race to the death. In all, it lasts 25 minutes and is full of ever-changing drama. Beethoven keeps hitting the bottom notes on his new Erard, testing the pianoforte almost to destruction. He crams more action into this sonata than, perhaps, any other and pianists seize licence to make of it what they will. Of Beethoven himself, playing this sonata, it was observed that ‘the moment he is seated at the piano he is evidently unconscious that there is anything else in existence.’

Of all the pianists who addressed this sonata on record, the first looked most like Beethoven, and maybe sound like him, too. Frederic Lamond was a Scotsman who studied with Liszt and may even have played Beethoven’s Broadwood piano, which Liszt kept at his home in Weimar. Lamond was turning 60 when he made this premiere recording of the Appassionata in March 1927 and his handling of the fast parts is not always immaculate. The poetry of his playing in the middle movement is also a trifle mundane. But the physical resemblance and the linear connection through Liszt make this compulsory listening as a benchmark for all that succeed him.

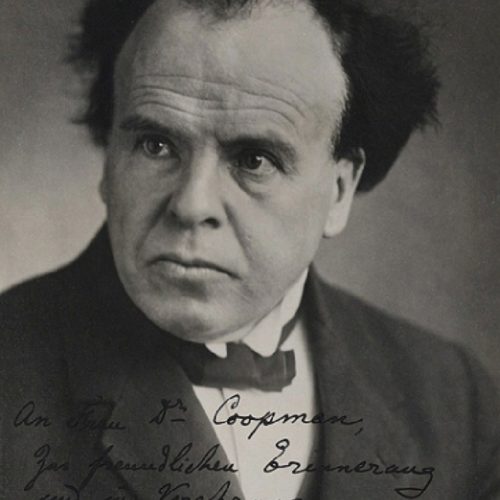

Arthur Schnabel, a full generation younger, knows the meaning of passion and pursues it with a vengeance. The finale is reckless, headlong, madcap, irresistible. Hard to imagine that some disparaged Schnabel as over-analytical. He could improvise his way out of a Houdini knot and this performance stands among his greatest monuments. I still find myself shaking my head in disbelief at the tenth hearing.

No less arresting is Emil Gilels, whom DG commissioned to record the complete sonatas in the 1970s. Temperamentally cautious but possessed of a technique that encompassed unlimited notes at once. Gilels lets the sonata unfold as if by its own volition. What we hear is the unravelling of Beethoven’s pursuit of love – at this time, one of two sisters call von Brunswick, he wasn’t sure which – in the manner in which the composer scribbled it down at his cottage desk. Gilels is another with a head like Beethoven’s and a life of inner turmoil. The recording, made in Berlin’s Jesus-Christus-Kirche is among the clearest and most perfectly balanced of the pre-digital age.

Neither Arthur Rubinstein nor Vladimir Horowitz was a Beethoven specialist and both address the passions of this sonata in ways that defy convention, Rubinstein by thundering away in the lower Steinway regions like a faulty heating system and Horowitz by picking out single notes, holding them to the light and asking us to admire them while he decides what to do next. Both are exemplars of a romantic school of pianism that will always have its admirers. Rudolf Serkin, of a more clinical disposition, dictates a prescriptive remedy for the sonata and brooks no contradiction – least of all among American critics, who consider him definitive. His son, Peter Serkin, is in some ways more appealing for his quizzical, questing approach to the finale and for his daring in taking on his father’s legacy – and besting it.

Among other historical oddities is a 1947 Abbey Road performance by the exiled Russian composer Nikolai Medtner, wayward and bleak but reflective of the way his friend Rachmaninov might have approached this work. I am always fascinated by the Frenchman Yves Nat (1954), an almost forgotten teacher of many fine pianist who played with an elegance that transcended mere accuracy. Elly Ney (1957), a favourite with the Nazi leadership, is undreamingly odious. Wilhelm Kempff (1964), no less of a Nazi lackey, is faultless and full of fantasy.

On my reject pile are the unimgnative Van Cliburn and the madly over-imaginative Glenn Gould, the miscast Lazar Berman and the unsmiling though intermittently exciting Yevgeny Kissin. Yundi Li, the first Chinese winner of the Chopin Competition, is out to set new speed records against his arch-rival Lang Lang.

Among current contenders I listen with unfailing delight to the Argentine Ingrid Fliter, who occupies her own time zone without ever taxing the listener’s patience and delivers glistening tone clusters that melt like snow on the tongue. I find the Appassionata to be one of the summits of Igor Levit’s ever-intriguing cycle and I’m very much taken with an Idagio exclusive – Mikhail Pletnev’s 2018 Verbier recital, notwithstanding ragged sound.

When all’s said and done, however, it’s still Gilels first and last.